2 days

Private Tour

English

UP TO 12 GUESTS

2 Days Private Tour: Persian War

Got a Question?

Contact UsHighlights

2 Days Marathon & Thermopylae private tour

Day 1st:

- Tumulus of Athenians

- Marathon Archaeological Museum

- Marathon Battlefield – Marathon Bay

- Marathon Lake

- Thermopylae Battlefield

- Historical Center of Thermopylae’s – Warm springs

- Arachova

Overnight: Delphi

Day 2nd:

- Village of Delphi

- The Oracle of Delphi – Museum of Delphi

- Sanctuary Athena Pronea – Gymnasium

- Plataies Battlefield

- Salamis Battlefield

- Drive to Athens

Itinerary

1st Day:

From Athens, we will drive towards the sacred plane of Marathon through the Attica highway and Marathon Avenue where the original Marathon race passes from, and you can see signs that count each kilometer. Later we will reach the Tumulus of Athenians; the site represents the courage, bravery and finally the victory of the Athenians against the Persians in 490 BCE. Also, you will visit the Marathon Battlefield and Archaeological Museum of Marathon and a prehistoric cemetery that presents proof of the first civilized presence. From there we will drive by the city of Marathon.

Before leaving for Thermopylae we will make our last stop at Lake Marathon, on the slopes of Mt Penteli, an artificial lake functioning still today as the main water reservoir for Athens. Apart from the magnificent view, you will be able to see the Marathon Dam, a miracle of engineering and the only one in the world made entirely of Pentelic marble (the king of marble, used for the Parthenon, on Acropolis Hill). Moreover, at the bottom, you will see an excellent modern replica of the treasury of the Athenians located initially in the sanctuary of Delphi.

Then we will drive to Thermopylae where 10 years after the Battle of Marathon, King Leonidas and the 300 Spartans heroically faced the Persian army. In the historical centre of the site you will enjoy a 3D movie, traveling through the time you will feel the presence of all who died for their freedom under a foreign conqueror. To complete the visit you will see the statue of Leonidas standing right opposite Kolonos Hill where the persisting Spartans left their last breath.

After spending some time in this area of serenity we will drive to the site of Delphi, an ancient Greek sanctuary with a PanHellenic character dedicated to god Apollo. It functioned as an Oracle and was considered ‘the naval’ the center of the word and is today a symbol of Greek cultural unity. The scenic location allows you to have a view of the Greek mountains and two more sites the Gymnasium and the secondary sanctuary of Athena Pronea. In the site, you will visit the Temple of Apollo where Pythia spoke to the oracles, the theater, and the stadium. While in the museum you will be able to see the famous charioteer and Gold Ivory statues. After the site, we will have our lunch at the modern village of Delphi with a view of the mountains of Fokis.

Before we leave we will stop at a point known for its great view, you will see the Corinthian sea, the port of Itea and the valley full of olive trees (olive sea) and our last destination will be the village of Arachova. A mountainous village built on a cliff 900 m above sea level very close to the Parnassus ski resort. You will have time to make an evening walk and enjoy a local dinner after settling at the hotel.

2nd Day:

On the following day, we will drive on the slopes of mountain Parnassus by the city of Livadia to reach the battlefield of Plataies where the last decisive battle was held between the united ancient Greek cities and the diminished Persian army 479 BCE. Lastly passing through the city of Thebes we will reach the coast of Attica and the Saronic Gulf and make a stop at Perama Port to see the narrow sea path of the island of Salamis where the historical naval battle took place between the Athenians and the Persians in 480 BCE. There you will have a view of the exact point where the Athenian navy lead by Themistocles destroyed the huge Persian ships. One of the victories that defined the future of the Greek homeland. After a traditional Greek lunch, we will make our way back to Athens.

Inclusions - Exclusions

Private Tours are personal and flexible just for you and your party.

Inclusions:

- Professional Drivers with Deep knowledge of history. [Not licensed to accompany you in any site.]

-

Accommodation and breakfast (according to your booking)

- Hotel pickup and drop-off

- Bottled water

- Guaranteed to skip the long lines / Tickets are NOT included.

Exclusions:

- Entrance Fees

- Licensed Tour guide on request (Additional cost)

-

Accommodation and breakfast (according to your booking)

- Personal expenses (drinks, meals, etc.)

- Airport Pick Up and drop-off (Additional cost)

Entrance Fees

ADMISSION FEES FOR SITES:

Summer Period: 33€ per person

(1 April – 31 October)

Marathon Tomb & Museum: 10€ (08:00- 15:30, Tuesdays closed)

Thermopylae’s Historical Center: 3€ (09:00- 17:00)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Winter Period: 33€ per person

(1 November – 31 March)

Marathon Tomb & Museum: 10€ (08:00- 15:30, Tuesdays closed)

Thermopylae’s Historical Center: 3€ (09:00- 17:00)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Free admission days:

- 6 March (in memory of Melina Mercouri)

- 18 April (International Monuments Day)

- 18 May (International Museums Day)

- The last weekend of September annually (European Heritage Days)

- Every first and third Sunday from November 1st to March 31st

- 28 October

Holidays:

- 1 January: closed

- 25 March: closed

- 1 May: closed

- Easter Sunday: closed

- 25 December: closed

- 26 December: closed

Free admission for:

- Children & young people up to the age of 25 from EU Member- States

- Children & young people from up to the age of 18 from Non- European Union countries

- Persons over 25 years, being in secondary education & vocational schools from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers during the visits of schools & institutions of Primary, Secondary & Tertiary education from EU Member- States

- People entitled to Social Solidarity income & members depending on them

- Persons with disabilities & one escort (only in the case of 67% disability)

- Refugees

- Official guests of the Greek State

- Members of ICOM & ICOMOS

- Members of societies & Associations of friends of State Museums & Archaeological sites

- Scientists licensed for photographing, studying, designing or publishing antiquities

- Journalists

- Holders of a 3- year Free Entry Pass

Reduced admission for:

- Senior citizens over 65 from Greece or other EU member-states, during

the period from 1st of October to 31st of May - Parents accompanying primary education schools visits from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers of educational visits of schools & institutions of primary, secondary & tertiary education from non European Union countries

Reduced & free entrance only upon presentation of the required documents

History

Marathon Battlefield:

At Marathon, we stood alone against Persia. And our courage in that mighty endeavor defeated the men of 46 nations.

Marathon was a battle of opposites. A tiny democratic city-state opposed a despotic empire hundreds of times its size. One army was almost entirely composed of armored infantrymen, the other of horsemen and archers. This clash of cultures was profoundly to affect the subsequent development of Western civilization.

For the city-state was Athens, where a functioning democracy had been created just two decades previously. The previous ruler of Athens, Hippias, had fled to the court of Darius 1 (521 -486 BC), king of Persia, whose empire stretched from the Aegean Sea to the banks of the Indus. Until they were conquered by Persia, the Greek colonies in Asia Minor had been independent. Unsurprisingly, they felt a greater affinity with their former homeland of Greece than with their ruler thousands of miles away in Persia. The Greeks of Asia Minor rebelled against the Persians and were assisted by Athenian soldiers who captured and burned Sardis, the capital of Lydia, in 498. Herodotus, the historian tells us:

‘Darius enquired who these Athenians were, and on being told … he prayed “Grant to me, God, that might punish them”, and he set a slave to tell him three times as he sat down to dinner “Master, remember Athenians”.’

Marathon, some 40 km (25 miles) east of Athens. Modern research has moved the date of this landing to August from the traditional date in early September. The size of the invading force is uncertain, with some estimates as high as 100,000 men. Probably there were about 44,000 men, including oarsmen and cavalry. Marathon was chosen because it was sufficiently far from Athens for an orderly disembarkation and because the flat ground suited the Persian cavalry, which outmatched the Greek horse.

Hippias, the former tyrant of Athens, accompanied the invaders. It was hoped that his presence might inspire a coup by the conservative aristocrats of Athens and bring about a bloodless surrender.

The rest of Greece was cowed into neutrality. Even the Spartans, the foremost military power in Greece, discovered a number of pressing religious rituals which would keep them occupied for the duration of the crisis. Only Plataea, a tiny dependency of Athens, sent reinforcements to the Athenian force which mustered before the plain of Marathon, in an area called Vrana between the hills and the sea.

The Athenians had about 7,200 men. They were mostly hoplites, a term which comes from the hoplon, the large circular shield which they carried. Each shield also offered support to the soldier on the shield bearer’s left, allowing this man to use his protected right arm to stab at the enemy with his principal weapon – the long spear. The Persian infantry preferred the bow and were fearsomely adept with it. They fired from behind large wicker shields which protected them from enemy bow fire, but were of doubtful value against attacking infantry.

Miltiades, the Athenian leader, knew his enemy, for he had once served in the Persian army. Now he had to convince a board of ten fellow generals that his plan of attack would succeed. Each general commanded for one day in turn and, though they ceded that command to Miltiades, he still waited until his allotted day before ordering the attack.

This delay was probably for the military rather than political reasons. To neutralize the superior Persian cavalry the Athenians might have needed to bring up abates, spiky wooden defenses, to guard their flanks. Or they might have waited for the Persian cavalry to consume their available supplies and be forced to go foraging. Or Datis, the Persian commander, might have broken the deadlock by ordering a march on Athens. The Athenians deployed most of their strength on the wings, perhaps to buffer a cavalry thrust, or so that they could extend their line to counter a Persian envelopment. This left the center dangerously weak, especially as the toughest of the Persian troops were deployed against it. They charged down the slight downhill slope at a run. The startled Persians misjudged the speed of the Athenian advance, and many of their arrows sped over the hoplites’ heads and landed harmlessly behind them.

Though caught off balance, the Persians were tough and resilient fighters. They broke the Athenian center and drove through towards Athens. But the hoplite force destroyed the wings and rolled them up in disorder before turning on the Persian regulars who had broken their center. The fight boiled through the Persian camp as the Persians struggled to regain their ships, with those who failed being driven into the marshes behind the camp.

The Athenians captured only seven ships –perhaps because the Persian cavalry belatedly reappeared. Nevertheless, it was a stunning victory. Over 6,000 Persians lay dead for the loss of 192 on the Athenian side. But there was no time for self-congratulation. The Persian fleet then started heading down the coast to where Athens lay undefended. In the subsequent race between the army on land and the army at sea, the Athenians were again victorious. On seeing the Athenian army mustered to oppose their landing, the Persians hesitated briefly, then sailed away.

Outcome:

Without a Greek victory at Marathon, Athens might never have produced Sophocles, Herodotus, Socrates, Plato or Aristotle. The word might never have known Euclid, Pericles or Demosthenes – in short, the cultural heritage of Western civilization would have been profoundly altered.

Nor would a young runner called Pheidippides have brought news of the victory to Athens. Pheidippides had earlier gone to Sparta asking for help, and now his heart gave way under the strain of his exertions. But a run of 41 km (26 miles) is still named after the battle from which he came – a marathon.

COMBATANTS:

Greeks:

10,000 men, of which 7,200 were Athenian hoplite infantrymen

Commanded by Miltiades and Callimachus, 192 dead

Persians:

45,000 – 50,000 men

Commanded by Datis, 6,400 dead (according to the Greeks)

Marathon Race History:

A race of 42,195 meters that designates the grandeur of human strength. A legend of 2.500 years, beginning with the myth of Pheidippides and reaching the modern heroes of classic sports. A race that unites millions of people all around the world. This is what the marathon run is about and what follows is its history…

Nenikékamen, (“We have won”)

The birth of the marathon run, basically identifies with the epic Battle of Marathon, in 490 b.c. The historians talk about the transmission of the joyous announcement of the Greek victory, from Marathon to Athens, by a soldier that covered 42,195 meters, in order to get from the plain of the battle to the current Greek capital. According to the legend, this soldier was no one else but Pheidippides, the famous runner of those times, who – according to Herodotus – was assigned to run a distance of 1.140 stages (more than two hundred kilometers) in two days, in order to get from Marathon to Sparta and ask for the help of Spartans, as soon as the Persians disembarked on the Attica bay. Tradition says that, as soon as Pheidippides entered the settings of the Assembly of Parliament, he exclaimed the prominent “Nenikikamen” whereupon he promptly died of exhaustion …

No historical report, however, confirm that Pheidippides was the one who ran first the distance Marathon- Athens

On the 1st century a.c., Ploutarchos stated that the announcement of the Greek victory reached Athens through a simple Greek soldier, who fought in the Battle, named “Efklis”. Wearing his armor, Efklis ran 42.195 meters and in his footsteps, were meant to walk millions of people, centuries later…

The marathon in modern times:

When the modern Olympics began in 1896, the initiators and organizers were looking for a great popularizing event, recalling the ancient glory of Greece. The idea of a marathon race came from Michel Bréal, who wanted the event to feature in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 in Athens. This idea was heavily supported by Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, as well as by the Greeks. The Greeks staged a selection race for the Olympic marathon on 10 March 1896 that was won by Charilaos Vasilakos in 3 hours and 18 minutes (with the future winner of the introductory Olympic Games marathon, Spyridon “Spyros” Louis, coming in fifth). The winner of the first Olympic Marathon, on 10 April 1896 (a male-only race), was Spyridon Louis, a Greek water-carrier, in 2 hours 58 minutes and 50 seconds. The marathon of the 2004 Summer Olympics was run on the traditional route from Marathon to Athens, ending at Panathinaiko Stadium, the venue for the 1896 Summer Olympics. That Men’s marathon was won by Italian Stefano Baldini in 2 hours 10 minutes and 55 seconds.

Thermopylae:

Thermopylae is a mountain pass near the sea in northern Greece which was the site of several battles in antiquity, the most famous being that between Persians and Greeks in August 480 BCE. Despite being greatly inferior in numbers, the Greeks held the narrow pass for three days with Spartan King Leonidas fighting a last-ditch defense with a small force of Spartans and other Greek hoplites. Ultimately the Persians took control of the pass, but the heroic defeat of Leonidas would assume legendary proportions for later generations of Greeks, and within a year the Persian invasion would be repulsed at the battles of Salamis and Plataea.

CONTEXT: THE PERSIAN WARS

By the first years of the 5th century BCE, Persia, under the rule of Darius (r. 522-486 BCE), was already expanding into mainland Europe and had subjugated Thrace and Macedonia. Next in king, Darius’ sights were Athens and the rest of Greece. Just why Greece was craved by Persia is unclear. Wealth and resources seem an unlikely motive; other more plausible suggestions include the need to increase the prestige of the king at home or to quell once and for all a collection of potentially troublesome rebel states on the western border of the empire.

Whatever the exact motives, in 491 BCE Darius sent envoys to call for the Greeks’ submission to Persian rule. The Greeks sent a no-nonsense reply by executing the envoys, and Athens and Sparta promised to form an alliance for the defense of Greece. Darius’ response to this diplomatic outrage was to launch a naval force of 600 ships and 25,000 men to attack the Cyclades and Euboea, leaving the Persians just one step away from the rest of Greece. In 490 BCE Greek forces led by Athens met the Persians in battle at Marathon and defeated the invaders. The battle would take on mythical status amongst the Greeks, but in reality, it was merely the opening overture of a long war with several other battles making up the principal acts. Persia, with the largest empire in the world, was vastly superior in men and resources and now these would be fully utilized for a full-scale attack.

In 486 BCE Xerxes became king upon the death of Darius and massive preparations for an invasion were made. Depots of equipment and supplies were laid, a canal dug at Chalkidiki, and boat bridges built across the Hellespont to facilitate the movement of troops. Greece was about to face its greatest ever threat, and even the oracle at Delphi ominously advised the Athenians to ‘fly to the world’s end’.

THE PASS OF THERMOPYLAE

When news of the invading force reached Greece, the initial Greek reaction was to send a force of 10,000 hoplites to hold a position at the valley of Tempē near Mt. Olympos, but these withdrew when the massive size of the invading army was revealed. Then after much discussion and compromise between Greek city-states, suspicious of each other’s motives, a joint army of between 6,000 and 7,000 men was sent to defend the pass at Thermopylae through which the Persians must enter to access mainland Greece. The Greek forces included 300 Spartans and their helots with 2,120 Arcadians, 1,000 Lokrians, 1,000 Phokians, 700 Thespians, 400 Corinthians, 400 Thebans, 200 men from Phleious, and 80 Mycenaeans.

The relatively small size of the defending force has been explained as reluctance by some Greek city-states to commit troops so far north, and/or due to religious motives, for it was the period of the sacred games at Olympia and the most important Spartan religious festival, the Karneia, and no fighting was permitted during these events. Indeed, for this very reason, the Spartans had arrived too late at the earlier battle of Marathon. Therefore, the Spartans, widely credited as being the best fighters in Greece and the only city-state with a professional army, contributed only a small advance force of 300 hoplites (from an estimated 8,000 available) to the Greek defensive force, these few being chosen from men with male heirs.

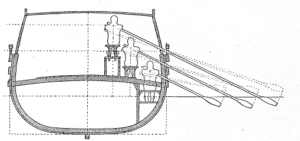

In addition to the land forces, the Greek city-states sent a fleet of trireme warships that held position off the coast of Artemision (or Artemisium) on the northern coast of Euboea, 40 nautical miles from Thermopylae. The Greeks would amass over 300 triremes and perhaps their main purpose was to prevent the Persian fleet sailing down the inland coast of Lokris and Boeotia.

The pass of Thermopylae, located 150 km north of Athens was an excellent choice for defense with steep mountains running down into the sea leaving only a narrow marshy area along the coast. The pass had also been fortified by the local Phokians who built a defensive wall running from the so-called Middle Gate down to the sea. The wall was in a state of ruin, but the Spartans made the best repairs they could in the circumstances. It was here, then, in a 15-meter wide gap with a sheer cliff protecting their left flank and the sea on their right that the Greeks chose to make a stand against the invading army. Having somewhere in the region of 80,000 troops at his disposal, the Persian king, who led the invasion in person, first waited four days in the expectation that the Greeks would flee in panic. When the Greeks held their position, Xerxes once again sent envoys to offer the defenders the last chance to surrender without bloodshed if the Greeks would only lay down their arms. Leonidas’ bullish response to Xerxes request was ‘molōn labe’ or ‘come and get them’ and so battle commenced.

HOPLITES VS ARCHERS

The two opposing armies were essentially representative of the two approaches to Classical warfare – the Persians favored long-range assault using archers followed up with a cavalry charge, whilst the Greeks favored heavily-armored hoplites, arranged in a densely packed formation called the phalanx, with each man carrying a heavy round bronze shield and fighting at close quarters using spears and swords. The Persian infantry carried a lightweight (often crescent-shaped) wicker shield and were armed with a long dagger or battleax, a short spear, and composite  bow. The Persian forces also included the Immortals, an elite force of 10,000 who were probably better protected with armor and armed with spears. The Persian cavalry were armed as the foot soldiers, with a bow and an additional two javelins for throwing and thrusting. Cavalry, usually operating on the flanks of the main battle, were used to mop up opposing infantry put in disarray after they had been subjected to repeated showers from the archers. Although the Persians had enjoyed the upper hand in previous contests during the recent Ionian revolt, the terrain at Thermopylae would better suit the Greek approach to warfare.

bow. The Persian forces also included the Immortals, an elite force of 10,000 who were probably better protected with armor and armed with spears. The Persian cavalry were armed as the foot soldiers, with a bow and an additional two javelins for throwing and thrusting. Cavalry, usually operating on the flanks of the main battle, were used to mop up opposing infantry put in disarray after they had been subjected to repeated showers from the archers. Although the Persians had enjoyed the upper hand in previous contests during the recent Ionian revolt, the terrain at Thermopylae would better suit the Greek approach to warfare.

Although the Persian tactic of rapidly firing vast numbers of arrows into the enemy must have been an awesome sight, the lightness of the arrows meant that they were largely ineffective against the bronze-armored hoplites. Indeed, Spartan indifference is epitomized by Dieneces, who, when told that the Persian arrows would be so dense as to darken the sun, replied that in that case, the Spartans would have the pleasure of fighting in the shade. At close quarters, the longer spears, heavier swords, better armor, and rigid discipline of the phalanx formation meant that the Greek hoplites would have all of the advantages, and in the narrow confines of the terrain, the Persians would struggle to make their vastly superior numbers count.

BATTLE

On the first day, Xerxes sent his Median and Kissian troops, and after their failure to clear the pass, the elite Immortals entered the battle but in the brutal close-quarter fighting, the Greeks held firm. The Greek tactic of simulating a disorganized retreat and then turning on the enemy in the phalanx formation also worked well, lessening the threat from Persian arrows and perhaps the hoplites surprised the Persians with their disciplined mobility, a benefit of being a professionally trained army.

The second day followed the pattern of the first, and the Greek forces still held the pass. However, an unscrupulous traitor was about to tip the balance in favor of the invaders. Ephialtes, son of Eurydemos, a local shepherd from Trachis, seeking reward from Xerxes, informed the Persians of an alternative route –the Anopaia path– which would allow them to avoid the majority of the enemy forces and attack their southern flank. Leonidas had stationed the contingent of Phokian troops to guard this vital point but they, thinking themselves the primary target of this new development, withdrew to a higher defensive position when the Immortals attacked. This suited the Persians as they could now continue unobstructed along the mountain path and arrive behind the main Greek force. With their position now seemingly hopeless, and before their retreat was cut off completely, the bulk of the Greek forces were ordered to withdraw by Leonidas.

LAST STAND

The Spartan king, on the third day of the battle, rallied his small force – the survivors from the original Spartan 300, 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans – and made a rearguard stand to defend the  pass to the last man in the hope of delaying the Persians progress, in order to allow the rest of the Greek force to retreat or also possibly to await relief from a larger Greek force. Early in the morning, the hoplites once more met the enemy, but this time Xerxes could attack from both front and rear and planned to do so but, in the event, the Immortals behind the Greeks were late on arrival. Leonidas moved his troops to the widest part of the pass to utilize all of his men at once, and in the ensuing clash, the Spartan king was killed. His comrades then fought fiercely to recover the body of the fallen king. Meanwhile, the Immortals now entered the fray behind the Greeks who retreated to a high mound behind the Phokian wall. Perhaps at this point, the Theban contingent may have surrendered (although this is disputed amongst scholars). The remaining hoplites now trapped and without their inspirational king, were subjected to a barrage of Persian arrows until no man was left standing. After the battle, Xerxes ordered that Leonidas’ head be put on a stake and displayed at the battlefield. As Herodotus claims in his account of the battle in book VII of The Histories, the Oracle at Delphi had been proved right when she proclaimed that either Sparta or one of her kings must fall.

pass to the last man in the hope of delaying the Persians progress, in order to allow the rest of the Greek force to retreat or also possibly to await relief from a larger Greek force. Early in the morning, the hoplites once more met the enemy, but this time Xerxes could attack from both front and rear and planned to do so but, in the event, the Immortals behind the Greeks were late on arrival. Leonidas moved his troops to the widest part of the pass to utilize all of his men at once, and in the ensuing clash, the Spartan king was killed. His comrades then fought fiercely to recover the body of the fallen king. Meanwhile, the Immortals now entered the fray behind the Greeks who retreated to a high mound behind the Phokian wall. Perhaps at this point, the Theban contingent may have surrendered (although this is disputed amongst scholars). The remaining hoplites now trapped and without their inspirational king, were subjected to a barrage of Persian arrows until no man was left standing. After the battle, Xerxes ordered that Leonidas’ head be put on a stake and displayed at the battlefield. As Herodotus claims in his account of the battle in book VII of The Histories, the Oracle at Delphi had been proved right when she proclaimed that either Sparta or one of her kings must fall.

Meanwhile, at Artemision, the Persians were battling the elements rather than the Greeks, as they lost 400 triremes in a storm off the coast of Magnesia and more in a second storm off Euboea. When the two fleets finally met, the Greeks fought late in the day and therefore limited the duration of each skirmish which diminished the numerical advantage held by the Persians. The result of the battle was, however, indecisive and on news of Leonidas’ defeat, the fleet withdrew to Salamis.

THE AFTERMATH

The battle of Thermopylae, and particularly the Spartans’ role in it, soon acquired mythical status amongst the Greeks. Free men, in respect of their own laws, had sacrificed themselves in order to defend their way of life against foreign aggression. As Simonedes’ epitaph at the site of the fallen stated: ‘Go tell the Spartans, you who read: We took their orders and here lie dead’.

A glorious defeat maybe, but the fact remained that the way was now clear for Xerxes to push on into mainland Greece. The Greeks, though, were far from finished, and despite many states now turning over to the Persians and Athens itself being sacked, a Greek army led by Leonidas’ brother Kleombrotos began to build a defensive wall near Corinth. Winter halted the land campaign, though, and at Salamis, the Greek fleet maneuvered the Persians into shallow waters and won a resounding victory. Xerxes returned home to his palace at Sousa and left the gifted general Mardonius in charge of the invasion. After a series of political negotiations, it became clear that the Persians would not gain victory through diplomacy and the two armies met at Plataea in August 479 BCE. The Greeks, fielding the largest hoplite army ever seen, won the battle and finally ended Xerxes’ ambitions in Greece.

As an interesting footnote: the important strategic position of Thermopylae meant that it was once more the scene of battle in 279 BCE when the Greeks faced invading Gauls, in 191 BCE when a Roman army defeated Antiochus III, and even as recent as 1941 CE when Allied New Zealand forces clashed with those of Germany.

Delphi:

Delphi was an important ancient Greek religious sanctuary sacred to the god Apollo. Located on Mt. Parnassus near the Gulf of Corinth, the sanctuary was home to the famous oracle of Apollo which gave cryptic predictions and guidance to both city-states and individuals. In addition, Delphi was also home to the PanHellenic Pythian Games.

MYTHOLOGY & ORIGINS:

The site was first settled in Mycenaean times in the late Bronze Age (1500 – 1100 BCE) but took on its religious significance from around 800 BCE. The original name of the sanctuary was Pytho after the snake which Apollo was believed to have killed there. Offerings at the site from this period include small clay statues (the earliest), bronze figurines, and richly decorated bronze tripods.

Delphi was also considered the center of the world, for in Greek mythology Zeus released two eagles, one to the east and another to the west, and Delphi was the point at which they met after encircling the world. This fact was represented by the omphalos (or navel), a dome-shaped stone that stood outside Apollo’s temple and which also marked the spot where Apollo killed the Python.

APOLLO’S ORACLE:

The oracle of Apollo at Delphi was famed throughout the Greek world and even beyond. The oracle – the Pythia or priestess – would answer questions put to her by visitors wishing to be guided in their future actions. The whole process was a lengthy one, usually taking up a whole day and only carried out on specific days of the year. First, the priestess would perform various actions of purification such as washing in the nearby Castalian Spring, burning laurel leaves and drinking holy water. Next an animal – usually a goat – was sacrificed. The party seeking advice would then offer a pelanos – a sort of pie – before being allowed into the inner temple where the priestess resided and gave her pronouncements, possibly in a drug or natural gas-induced state of ecstasy.

Perhaps the most famous consultant of the Delphic oracle was Croesus, the fabulously rich King of Lydia who, when faced with a war against the Persians, asked the oracle’s advice. The oracle stated that if Croesus went to war then a great empire would surely fall. Reassured by this, the king took on the mighty Cyrus. However, the Lydians were overpowered at Sardis and it was the Lydian empire which fell, a lesson that the oracle could easily be misinterpreted by the unwise or over-confident.

PANHELLENIC GAMES:

Delphi, as with the other major religious sites of Olympia, Nemea, and Isthmia, held games to honor various gods of the Greek religion. The Pythian Games of Delphi began sometime between 591 and 585 BCE and were initially held every eight years, with the only event being a musical competition where solo singers accompanied themselves on a kithara to sing a hymn to Apollo. Later, more musical contests and athletic events were added to the program, and the games were held every four years with only the Olympic Games being more important. The principal prize for victors in the games was a crown of laurel or bay leaves.

The site and games were managed by the independent Delphic amphictiony – a council with representatives from various nearby city-states – which asked for taxes, collected offerings, invested in construction programs, and even organized military campaigns in the Four Sacred Wars, fought to remedy sacrilegious acts against Apollo committed by the states of Crisa, Phocis, and Amphissa.

ARCHITECTURE:

The first temple in the area was built in the 7th century BCE and was a replacement for less substantial buildings of worship which had stood before it. The focal point of the sanctuary, the Doric temple of Apollo, was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 548 BCE. A second temple, again Doric in style, was completed in 510 BCE. Measuring some 60 by 24 meters, the facade had six columns whilst the sides had 15. This temple was destroyed by an earthquake in 373 BCE and was replaced by a similarly sized temple in 330 BCE. This was constructed with poros stone coated in stucco. Marble sculpture was also added as decoration along with Persian shields taken at the Battle of Marathon. This is the temple survives, although only partially, today.

The first temple in the area was built in the 7th century BCE and was a replacement for less substantial buildings of worship which had stood before it. The focal point of the sanctuary, the Doric temple of Apollo, was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 548 BCE. A second temple, again Doric in style, was completed in 510 BCE. Measuring some 60 by 24 meters, the facade had six columns whilst the sides had 15. This temple was destroyed by an earthquake in 373 BCE and was replaced by a similarly sized temple in 330 BCE. This was constructed with poros stone coated in stucco. Marble sculpture was also added as decoration along with Persian shields taken at the Battle of Marathon. This is the temple survives, although only partially, today.

Other notable constructions were the theatre (with capacity for 5,000 spectators), temples to Athena (4th century BCE), a tholos with 13 Doric columns ( 580 BCE), stoas, a stadium (with capacity for 7,000 spectators), and around 20 treasuries, which were constructed to house the votive offerings and dedications from city-states all over Greece. Similarly, monuments were also erected to commemorate military victories and other important events. For example, the Spartan general Lysander erected a monument to celebrate his victory over Athens at Aegospotami. Other notable monuments were the great bronze Bull of Corcyra (580 BCE), the ten statues of the kings of Argos (369 BCE), a gold four-horse chariot offered by Rhodes, and a huge bronze statue of the Trojan Horse offered by the Argives (413 BCE). Lining the sacred way, from the sanctuary gate up to the temple of Apollo, the visitor must have been greatly impressed by the artistic and literal wealth on display. Alas, in most cases, only the monumental pedestals survive of these great statues, silent witnesses to lost grandeur.

DEMISE:

In 480 BCE the Persians attacked the sanctuary and in 279 BCE the sanctuary was attacked again, this time by the Gauls. During the 3rd century BCE that the site came under the control of the Aitolian League. In 191 BCE Delphi passed into Roman hands; however, the sanctuary and the games continued to be culturally important in Roman times, in particular under Hadrian. The decree by Theodosius in 393 CE to close all pagan sanctuaries resulted in Delphi’s gradual decline. A Christian community dwelt at the site for several centuries until its final abandonment in the 7th century CE.

The site was ‘rediscovered’ with the first modern excavations being carried out in 1880 CE by a team of French archaeologists. Notable finds were splendid metope sculptures from the treasury of the Athenians (c. 490 BCE) and the Siphnians (c. 525 BCE) depicting scenes from Greek mythology. In addition, a bronze charioteer in the severe style (480-460 BCE), the marble Sphinx of the Naxians (c. 560 BCE), the twin marble archaic statues – the kouroi of Argos (c. 580 BCE) and the richly decorated omphalos stone (c. 330 BCE) – all survive as testimony to the cultural and artistic wealth that Delphi had once enjoyed.

Battle of Plataies:

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BCE near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between united Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth, and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I. During the previous year the Persian force, led by the Persian king himself, had scored victories at the battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium and conquered Thessaly, Boeotia, Euboea, and Attica. However, later, at the Battle of Salamis, the combined Greek navy had won a decisive victory, preventing the conquest of the Peloponnese. Xerxes then retreated with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius to finish off the Greeks the following year. So In the summer of 479 BCE, the Greeks assembled a huge army and marched out of the Peloponnesus.

united Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth, and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I. During the previous year the Persian force, led by the Persian king himself, had scored victories at the battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium and conquered Thessaly, Boeotia, Euboea, and Attica. However, later, at the Battle of Salamis, the combined Greek navy had won a decisive victory, preventing the conquest of the Peloponnese. Xerxes then retreated with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius to finish off the Greeks the following year. So In the summer of 479 BCE, the Greeks assembled a huge army and marched out of the Peloponnesus.

The Persians retreated to Boeotia and built a fortified camp near Plataea. The Greeks, however, refused to be drawn into the prime cavalry terrain around the Persian camp, resulting in a standstill that lasted 11 days. When there supplies ran out, while trying to restock it looked like a retreat, the Greek battle line was broken. Thinking the Greeks in full retreat, Mardonius ordered his forces to go after them, but the Greeks (particularly the Spartans, Tegeans and Athenians) stopped and gave battle, crushing the lightly armed Persian infantry and killing Mardonius. A large part of the Persian army was trapped in its camp. The destruction of this army, and the remains of the Persian navy, also crushed on the same day at the Battle of Mycale, decisively ended the invasion. After Plataea and Mycale the Greek allies would take the offensive against the Persians, marking a new phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. Although Plataea was a very important victory, it does not seem to have been attributed to the same significance as, for example, the Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon or the Spartan defeat at Thermopylae. Oh well, maybe when it too, is made into a movie.

Salamis:

In 480 BCE the Persians again invaded Greece, it King Xerxes, leading a huge army across from Anatolia, shadowed by a fleet of about 1,200 warships. Many of the southern Greek city-states banded together under Spartan leadership of Eurybiades by land and by sea. Coordinated attempts to block the advance of this army in the narrow pass of Thermopylae and hold up his fleet at Artemision failed when the Greek land forces were outflanked and forced to withdraw. A small Spartan and Thespiaean rear guard resisted heroically but was overwhelmed.

Herodotus Battles History- The combined Greek fleet moved to the island Salamis, abandoning the cities of Thebes and Athens to the enemy. A prophecy urging the Athenians to put their faith in a wooden wall caused some of them to fortify their Acropolis with timber, but the majority agreed with the elected general Themistocles that their best hope lay in the city’s 200 wooden, trireme warships, the largest contingent in the Greek fleet. After the evacuation of the Athenians to Salamis had been completed, the Greek fleet assembled in the bay on the eastern side of the island.

When the news came that the Acropolis of Athens had been occupied, the Spartan commander Eurybiades ordered his captains to withdraw under cover of darkness to a more defensible position on the Isthmus of Corinth but changed his mind later that night and the Greeks sailed out to confront the Persians the next morning. Herodotus claims that Themistocles sent a secret message to warn Xerxes that the Greeks were about to withdraw, causing him to send ships around Salamis to cut off the Greeks’ retreat and forcing Eurybiades to risk a battle.

This story is a highly dubious one, assuming as it does that King Xerxes and his commanders would trust such a message and that Themistocles would have thought it advantageous to provoke a Persian attack. It is more likely that the Persians planned to surround the Greeks, as they had attempted once before at Artemision. Their aim would have been to drive the Greek ships northwards and westwards out of the narrow channel between Salamis and the mainland, into the open waters of the Bay of Eleusis, and attack them from two sides. For this purpose, Xerxes dispatched 200 Egyptian ships the early evening to sail right around Salamis and come at the Greeks from the direction of Eleusis. He also sent a flotilla to cruise the waters around the southern end of the island, while his main fleet (around 600 ships) moved into position at the eastern approaches to the narrow straits, ready to advance at dawn.

The Greeks were made aware of these maneuvers by Aristeides, an exiled Athenian politician who had returned to join in the fight against the Persians and had probably been sent on a scouting mission to determine whether the escape route to the west was clear. His news was greeted with dismay in the Greek camp, but the commanders resolved to sail out at dawn and take the Persians on in the straits between Salamis and the mainland, hoping that the superior numbers of the enemy would count for less in such confined spaces.

The battle

In eager anticipation of a magnificent victory, King Xerxes positioned himself opposite Salamis with a good view of the small island of Psyttaleia, where a detachment of Persian troops had landed during the night. But instead of witnessing his fleet’s final triumph over the Greeks, Xerxes saw a naval disaster unfold before his very eyes. The various ethnic contingents of the Persian fleet were lined up several rows deep across the narrow channel with the Phoenicians on the right-wing, nearest to Xerxes’s position, and the Ionians on the left, nearest to Salamis. As they moved further into the channel their ships became so compacted and confused that they found it impossible to keep formation. The crews were tired and to make matters worse a strong swell developed, making it even harder for the ships to make headway. Themistocles had anticipated this and seems to have persuaded the other Greek commanders to delay engaging the Persians until they were clearly in disorder. With the Athenian ships leading, the Greeks rowed out from the shore and turned towards the enemy. On a given signal their fresh crews surged forward and broke through the Persian lines to ram individual ships as they struggled to maneuver.

The Persians would have been expecting the Greeks to flee before their superior force, according to the plan worked out the previous day. But, like all ancient battles, once the action had started it was impossible to keep to a specific plan, and the captains of the individual ships were forced to make decisions on the spot. The main decision made by many of Xerxes’s captains was to turn away from the attacking Greeks, causing confusion as they encountered more of their own ships trying to advance. In the resulting chaos, the Greek captains urged on their much fresher crews and pressed the attack with great success.

It is impossible to describe the full course of action in detail. Our main source, the writer Herodotus, offers only a series of anecdotes about various groups of combatants. It was claimed that 70 Corinthian ships under Adeimantos and fled towards the Bay of Eleusis. It is likely that this supposed cowardly, northward, a retreat which Herodotus presents as an Athenian slander against the Corinthians, may have been a deliberate move to engage the Egyptian squadron and prevent it from attacking the Greek rear. The Corinthians maintained that their ships did not encounter the Egyptians but returned to the battle and acquitted themselves, and other Greeks. One of the most colorful anecdotes concerns Artemisia, the ruler of Herodotus’s home city Alicarnassus, which was subject to the Persians. She was in command of her own ship and in the front line of the Persian fleet. When an Athenian trireme bore down on her she tried to escape but found her path blocked by other Persian ships. In desperation, she ordered her helmsman to ram one of them, which sank with the loss of all its crew. The pursuing Athenian captain assumed that Artemisia’s ship was on his side and changed course towards another Persian vessel. Xerxes and his advisors saw the incident and recognized Artemisia’s ship by its ensign, but their belief that she had sunk a Greek trireme then earned her the king’s admiration. Xerxes is also said to have remarked at this point, ‘My men have acted like women and my women like men.’

It is impossible to describe the full course of action in detail. Our main source, the writer Herodotus, offers only a series of anecdotes about various groups of combatants. It was claimed that 70 Corinthian ships under Adeimantos and fled towards the Bay of Eleusis. It is likely that this supposed cowardly, northward, a retreat which Herodotus presents as an Athenian slander against the Corinthians, may have been a deliberate move to engage the Egyptian squadron and prevent it from attacking the Greek rear. The Corinthians maintained that their ships did not encounter the Egyptians but returned to the battle and acquitted themselves, and other Greeks. One of the most colorful anecdotes concerns Artemisia, the ruler of Herodotus’s home city Alicarnassus, which was subject to the Persians. She was in command of her own ship and in the front line of the Persian fleet. When an Athenian trireme bore down on her she tried to escape but found her path blocked by other Persian ships. In desperation, she ordered her helmsman to ram one of them, which sank with the loss of all its crew. The pursuing Athenian captain assumed that Artemisia’s ship was on his side and changed course towards another Persian vessel. Xerxes and his advisors saw the incident and recognized Artemisia’s ship by its ensign, but their belief that she had sunk a Greek trireme then earned her the king’s admiration. Xerxes is also said to have remarked at this point, ‘My men have acted like women and my women like men.’

Another story concerns the Persian soldiers on the island of Psyttaleia. They were placed there in anticipation of the bulk of the Greek fleet being driven north and westwards away from the island. Instead, they were isolated from their own ships and left vulnerable to attack from the nearby shores of Salamis. Right before Xerxes’s eyes his elite troops, including three of his own nephews, were slaughtered by the Athenians.

Along the coast of Salamis, other Persians who managed to get ashore from their foundering ships were killed or captured. Towards the end of the day, the Persian fleet retreated in confusion to the Bay of Phaleron, having lost more than 200 ships and having failed in its objective of forcing the Greeks away from Salamis. The Greeks had lost only about 40 ships and sent the enemy back to their anchorage in disarray.

Aftermath

Xerxes took the remains of his fleet and much of his army back to Anatolia, leaving his general Mardonius with a substantial army in central Greece. The following year a Greek army led by the Spartan king Pausanias defeated them at Plataea, north of Athens, effectively freeing mainland Greece from the threat of Persian domination. Themistocles was honored by the Spartans for his part in the victory, but his own countrymen seem to have turned against him, eventually forcing him to take refuge with the Persians. Xerxes’s son Artaxerxes I made him governor of Magnesia on the Maeander River, where he died around 459 BCE.

COMBATANTS

Greeks: 390 ships Commanded by Eurybiades (Spartan), Themistocles (Athenian), Adeimantos (Corinthian) 40 ships lost

Persians: 1200 ships Commanded by King Xerxes Over 400 ships lost

Cancellation Policy

All cancellations must be confirmed by Olive Sea Travel.

Regarding the Multiple Day Tours:

Cancellations up to 30 Days before your service date are 100% refundable.

Cancellation Policy:

- Licensed Tour Guides and Hotels are external co-operators & they have their own cancellation policy.

- Apart from the above cancellation limits, NO refunds will be made. If though, you fail to make your appointment for reasons that are out of your hands, that would be, in connection with the operation of your airline or cruise ship or strikes, extreme weather conditions or mechanical failure, you will be refunded 100% of the paid amount.

- If your cancellation date is over TWO (2) months away from your reservation date, It has been known for third-party providers such as credit card companies, PayPal, etc. to charge a levy fee usually somewhere between 2-4%.

- Olive Sea Travel reserves the right to cancel your booking at any time, when reasons beyond our control arise, such as strikes, prevailing weather conditions, mechanical failures, etc. occur. In this unfortunate case, you shall be immediately notified via the email address you used when making your reservation and your payment WILL be refunded 100%.

Recommended for you