7 days

Private Tour

English

UP TO 12

7 Days Private Tour: Meteora-Ioannina-Thessaloniki-Litochoro & Delphi

Got a Question?

Contact UsHighlights

Dodoni & Pella private tour

1st Day:

- Thermopylae’s Battlefield – Leonidas statue

- The Monasteries of Meteora

- Kalambaka Village

Overnight: Kalambaka (Meteora)

2nd Day:

- Dodoni

- Village of Ioannina

Overnight: Ioannina

3rd Day:

- Metsovo

- Vergina (Royal Tombs) – Aigai Palace

- Thessaloniki

Overnight: Thessaloniki

4th Day:

- Pella Archaeological Site – Pella Museum

- White Tower

- Rotunda – The Galerius Arch

- Ano Poli (Upper City)

- Cathedral of the Patron Saint Demetrius

Overnight: Thessaloniki

5th Day:

- Dion Archaeological Park – Dion Archaeological Museum

- Leptokaria

- Olympus Mountain- Litochoro village

Overnight: Litochoro

6th Day:

- Village of Delphi

- The Oracle of Delphi – Museum of Delphi

- Sanctuary Athena Pronea – Gymnasium

Overnight: Delphi

7th Day:

- Arachova

- Hosios Loukas monastery

- Marathon Dam

- Marathon battlefield – Tumulus of Athenians

- Cape Sounion – Poseidon’s Temple

- Athenian Riviera – Glyfada – Voula

Itinerary

1st Day:

Your trip begins with a drive northbound following the national highway in order to reach Kalambaka. On our way, we will make a stop at Thermopylae, a location synonymous with legends and heroes. You will stand on the actual battlefield where in 480 BCE, the 300 Spartans and their King Leonidas heroically faced the Persian army. At the site will enjoy a 3D movie and like traveling through the time you will feel the presence of all who died for their freedom under a foreign conqueror. Before leaving the site you will see the statue of Leonidas looking to Kolonos Hill where the persisting Spartans left their last breath.

Continuing our drive we will go by the city of Lamia and Trikala to reach Kalambaka, the modest town that is surrounded by the rocks of Meteora. We will visit the monasteries high on the pillars and take a closer look at the holy rocks. On the rocks that are ‘like suspended in the air’ (that’s what Meteora means) there remains one of the largest and most important complexes of Eastern Orthodox Monasteries. This unusual location combines natural beauty and cultural heritage, a fact that makes them a unique destination between the world’s monuments. On our return, we will have lunch in the town of Kalambaka and later reach the hotel where you can rest for a few hours.

Later on, you have the option of an evening photo tour on the rocks under a magical sunset, being able to see a different perspective of the site or just stand at the edge of the rock and admire the miracle of nature and the Greek cavitation. Then dinner at the town of Kalambaka before overnighting.

2nd Day:

On the next day, we will depart for Ioannina. Different from other Greek cities Ioannina includes a preserved fortress in the center of the old town and is developed around a natural lake (Pamvotida). The lake is also one of a kind as has a small inhabited island just across from the city.

Before we explore Ioannina though we will first drive to the Ancient Greek Oracle of Dodoni where a huge site is preserved. It reveals where the ancient Greek theater, the Temple and the Oracle of Zeus functioned. Just before Ioannina, we will reach the region of Perama. Here you can visit the Cave of Perama, this timeless cave (covering a distance of 1,5 km) is full of openings with beautiful formations of stalagmites and stalactites created 1,5 million years ago. The last stop before the entering the city will be the Museum of Greek History (Wax Effigies) where you will see the historical community come alive.

Reaching Ioannina we will have lunch and then enjoy free time in the city. Wander around the old town or even visit the small island by the taxi boat (5min distance) where you can admire the house and the museum of Ali Pasha.

3rd Day:

After spending the night at Ioannina we will head towards Vergina. Following the countryside roads to soak up the landscape we will make a stop at Metsovo. A small mountainous town with traditionally build houses very famous for its cheese.

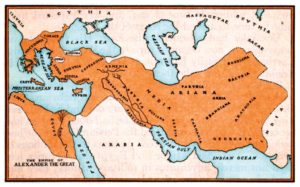

Following this small break we will continue to Vergina where you will be able to visit one of the most dazzling sites of the Macedonian Empire and come to understand why it was chosen as the capital of the Macedonian World. You will also enjoy the museum that developed around the original location of the Royal Tombs full of their golden belongings. And more importantly, you will encounter the imposing tomb of Philip the II, father of Alexander the Great. Close to the museum are the remains of the palace of Philip II. He was the king that had a vision, to unite all the ancient Greek cities for the first time, Philip made this PanHellenic idea come true before being murdered.

The last destination for the day will be Thessaloniki. Not very far from Vergina, it towers as the northern capital of Greece. Thessaloniki is a city that stands out for its cosmopolitan character and its splendid past. As it developed along the coast of the Thermaic Gulf it includes all the different characteristics that are consistent with the Greek element. We Greeks call it “the bride of the North”. Your evening will be free to walk in the city, locals usually stroll on the 3.5km walkway by the sea. Don’t forget to try some of the most popular traditional desserts such as “trigona Panoramatos” and “Bougatsa”.

4th Day:

After spending the night at Thessaloniki, in the morning we will depart for Pella. Located only 53 miles from Thessaloniki, Pella is one of the most important sites of the Hellenistic Period. Pella was chosen to be the capital of the huge Macedonian Empire, in the end, the 5th century BCE. We will visit the site which consists of public baths, sanctuaries, villas of wealthy Macedonians with unique mosaic decoration and of course the Agora of the city. The city which initially covered an area of 400 hectares and gradually became the cultural and commercial center of the Empire, was also the birthplace of Alexander the Great.

The next stop will be the museum of Pella, a modern museum that opened its doors in 2009 and has nothing to envy from the Greek museums located in big cities.

After our visit, we will drive back to Thessaloniki to have a traditional northern Greek lunch in the region of “Ladadika”. In the afternoon we will continue with a drive around the beautiful city to see all the highlights of the co-capital, the White Tower, the Arch of Galerius, the Rotunda, the Roman Agora and the cathedral of the Patron Saint Demetrius, the city wall and “Ano Poli (Upper City). The fortified Ano Poli offers a breathtaking view of the city and the Aegean Sea. The rest of the day will be free to enjoy more of the city, visit museums, walk-in Aristotelous square or visit the central commercial streets before our overnight.

5th Day:

On the following day, we will start off by driving southwards on the national highway to reach Dion. When we arrive at the village of Dion we will find the site and the archaeological museum. The ancient Greek city named after Zeus (in Greek Dias) that retained its importance in the Macedonian Period. Here Philip II and his son Alexander the Great made sacrifices to the Gods after dominating the Greek world and from here Alexander the Great set out towards Asia. Dion was a city of significant strategic importance according to the Macedonian kings. Today the sanctuary of Isis and other Egyptian Gods, the oldest sanctuary of Goddess Dimitra, a Hellenistic theater, a Roman theater and stadium, the mansion of god Dionysos  with wonderful mosaic decoration and many more public and private buildings can be visited. Moreover, the museum includes all the precious findings that have been excavated in the ancient city.

with wonderful mosaic decoration and many more public and private buildings can be visited. Moreover, the museum includes all the precious findings that have been excavated in the ancient city.

After the site, we will head towards Litochoro. Before we reach our destination for the day we will stop at the coast of Leptokaria to have a swim in the Aegean and lunch at a seaside fish tavern. Lastly, we will be on the slopes of Mt Olympus to reach the village of Litochoro, spend the rest of the day and overnight. Litochoro is the closest location of Mt Olympus at sea level. Its location makes it a popular destination for climbers. So, in a nutshell, we will stay at the foothill of the highest mountain in Greece, home to the 12 Gods of Olympus according to the Greek mythology.

6th Day:

Continuing the next morning we will follow the road through the countryside to reach the village of magical Delphi. Delphi was an ancient Greek sanctuary with a PanHellenic character dedicated to the God Apollo. It was used as an oracle and considered ‘the naval’ the center of the world. These days it is a symbol of Greek cultural unity. The scenic location allows you a view of the Greek mountains and two other sites the Gymnasium and the (secondary) sanctuary of Athena Pronea. In the site, you will enjoy visiting the Temple of Apollo where Pythia spoke to the oracles, the theater, and the stadium. Later in the museum, you will be able to see the famous charioteer and Gold Ivory statues.

Finishing with the site we will have lunch at the modern village of Delphi with a fantastic view of the Fokis mountains. Before we take off we will pause at a special location for its great view, you will see the Corinthian Sea, the port of Itea and the valley full of olive trees (olive sea).

Then our last destination for the day, the village of Arachova. Very close to the Parnassus ski resort Arachova is a mountainous village built on a cliff 900m above sea level. You will enjoy a local dinner and have time for an evening walk after settling at the hotel.

7th Day:

For our final day, we will say goodbye to Arachova to see a medieval monastery up close, the monastery of Osios Loukas. The monastery represents the second golden age of the Byzantine art (11th -12th  century) very well, in particular, its golden mosaic decoration and fine architecture.

century) very well, in particular, its golden mosaic decoration and fine architecture.

After spending some time in this calming atmosphere we will continue south on the national highway to reach our next destination Marathon.

On the way, we will stop at Lake Marathon which is the main water reservoir for Athens. Apart from the magnificent view, you will be able to see the Marathon Dam, a miracle of engineering. It is the only one in the world made entirely of Pentelic marble (the king of marbles and used for the Parthenon, on Acropolis Hill). Furthermore, at the bottom there is an excellent replica of the treasury of the Athenians (located in the sanctuary of Delphi).

Then we will come to the battlefield of Marathon and the Tumulus of Athenians. The sacred site represents courage, bravery and finally the victory of the Athenians against the Persians in 490 BCE. You will also visit the Archaeological Museum of Marathon and a prehistoric cemetery, proof of its first civilized presence.

Moving us to our last archaeological site of this amazing week, after a short drive (along the eastern coast of the Attica Peninsula) passing by Lavrio to reach Sounio. Entering the site you will be overwhelmed by the Temple of Poseidon, the ancient god of the sea. Enclosed by the remains of its fortification, the gateway portigos, and houses. Neighbouring is the remains of the temple Athena Souniada. Apart from the magnificent location and its archaeological interest, Cape Sounio is also recognized for its breathtaking sunset and view of the Greek islands. It is justly considered as one of the most romantic places in Greece and the world. Then we will drive towards a traditional tavern by the waterfront which serves fresh fish straight from the sea.

Our final drive will be towards Athens making our way through the coastal southern suburbs of Athens Vouliagmeni, Varkiza, Voula and Glifada widely known as the Athenian Riviera. Taking a break we will make a stop at Lake Vouliagmeni (mineral, therapeutic, natural lake) a real hidden treasure. The relaxing coastal ride back to Athens will conclude our tour.

Inclusions - Exclusions

Private Tours are personal and flexible just for you and your party.

Inclusions:

- Professional Drivers with Deep knowledge of history. [Not licensed to accompany you in any site.]

- Hotel pickup and drop-off

- Guaranteed to skip the long lines / Tickets are NOT included.

- Fuel surcharge

- Local taxes

- Bottled water

Exclusions:

- Licensed Tour guide on request (Additional cost)

-

Accommodation and breakfast

- Entrance Fees

- Personal expenses (drinks, meals, etc.)

- Airport Pick Up and drop-off (Additional cost)

Entrance Fees

ADMISSION FEES FOR SITES:

Summer Period: 154€ per person

(1 April – 31 October)

Thermopylae’s Historical Center: 3€ (09:00- 17:00)

Meteora Monasteries: (5€ per monastery)

St. Stephen’s Nunnery 09:00 -13:30 and 15:30 –17:30 (Mondays closed)

Great Meteoron Monastery 09:00 –15:00 (Tuesdays closed)

Roussanou Monastery 09:00 -16:00 (Wednesdays closed)

Holy Trinity Monastery 09:00 -16:00 (Thursdays closed)

Varlaam Monastery 09:00 –16:00 (Fridays closed)

St. Nikolaos Anapafsas Monastery 09:00 -17:00 (Fridays closed)

Dodoni: 15€ (08:00- 20:00)

Vergina Royal Tombs: 12€ (08:00- 20:00, Tuesdays 12:00- 20:00)

Archaeological Site-Palace: Under excavation

Thessaloniki White Tower: 4€ (08:00 -20:00)

Rotunda: 10€ (08:00 -20:00)

Pella Archaeological Site – Museum: 20€ (08:00- 20:00, Tuesdays 12:00- 20:00)

Dion Archaeological Park – Museum: 20€ (08:00 -20:00)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Hosios Loukas Monastery: 10€ (08:00- 15:30)

Marathon Tomb & Museum: 10€ (08:00- 15:30, Tuesdays closed)

Temple of Poseidon Sounio: 20€ (08:00- sunset, about 20:00)

Winter Period: 154€ per person

(1 November – 31 March)

Thermopylae’s Historical Center: 3€ (09:00- 17:00)

Meteora Monasteries: (5€ per monastery)

St. Stephen’s Nunnery 09:30 -13:00 and 15:00 –17:00 (Mondays closed)

Great Meteoron Monastery 09:00 –14:00 (Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays closed)

Roussanou Monastery 09:00 -14:00 (Wednesdays closed)

Holy Trinity Monastery 10:00 -16:00 (Thursdays closed)

Varlaam Monastery 09:00 –15:00 (Thursdays, Fridays closed)

St. Nikolaos Anapafsas Monastery 09:00 -15:00 (Fridays closed)

Dodoni: 15€ (08.30-15.30)

Vergina Royal Tombs: 12€ (09:00-17:00, Tuesdays closed)

Archaeological Site-Palace: Under excavation

Thessaloniki White Tower: 4€ (08:00 -20:00)

Rotunda: 5€ (08:00 -20:00)

Pella Archaeological Site – Museum: 20€ (8:30-15:30)

Dion Archaeological Park – Museum: 20€ (08:30-15:30, Tuesdays closed)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Hosios Loukas Monastery: 10€ (08:00- 15:30)

Marathon Tomb & Museum: 10€ (08:00- 15:30, Tuesdays closed)

Temple of Poseidon Sounio: 20€ (09:30- sunset, about 17:00)

Free admission days:

- 6 March (in memory of Melina Mercouri)

- 18 April (International Monuments Day)

- 18 May (International Museums Day)

- The last weekend of September annually (European Heritage Days)

- Every first and third Sunday from November 1st to March 31st

- 28 October

Holidays:

- 1 January: closed

- 25 March: closed

- 1 May: closed

- Easter Sunday: closed

- 25 December: closed

- 26 December: closed

Free admission for:

- Children & young people up to the age of 25 from EU Member- States

- Children & young people from up to the age of 18 from Non- European Union countries

- Persons over 25 years, being in secondary education & vocational schools from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers during the visits of schools & institutions of Primary, Secondary & Tertiary education from EU Member- States

- People entitled to Social Solidarity income & members depending on them

- Persons with disabilities & one escort (only in the case of 67% disability)

- Refugees

- Official guests of the Greek State

- Members of ICOM & ICOMOS

- Members of societies & Associations of friends of State Museums & Archaeological sites

- Scientists licensed for photographing, studying, designing or publishing antiquities

- Journalists

- Holders of a 3- year Free Entry Pass

Reduced admission for:

- Senior citizens over 65 from Greece or other EU member-states, during

the period from 1st of October to 31st of May - Parents accompanying primary education schools visits from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers of educational visits of schools & institutions of primary, secondary & tertiary education from non European Union countries

Reduced & free entrance only upon presentation of the required documents

History

Thermopylae:

Thermopylae is a mountain pass near the sea in northern Greece which was the site of several battles in antiquity, the most famous being that between Persians and Greeks in August 480 BCE. Despite being greatly inferior in numbers, the Greeks held the narrow pass for three days with Spartan King Leonidas fighting a last-ditch defense with a small force of Spartans and other Greek hoplites. Ultimately the Persians took control of the pass, but the heroic defeat of Leonidas would assume legendary proportions for later generations of Greeks, and within a year the Persian invasion would be repulsed at the battles of Salamis and Plataea.

THE PERSIAN WARS

By the first years of the 5th century BCE, Persia, under the rule of Darius (522 – 486 BCE), was already expanding into mainland Europe and had subjugated Thrace and Macedonia. Next in Κing Darius’ sights were Athens and the rest of Greece. Just why Greece was craved by Persia is unclear. Wealth and resources seem an unlikely motive; other more plausible suggestions include the need to increase the prestige of the king at home or to quell once and for all a collection of potentially troublesome rebel states on the western border of the empire.

Whatever the exact motives, in 491 BCE Darius sent envoys to call for the Greek’s submission to Persian rule. The Greeks sent a no-nonsense reply by executing the envoys, and Athens and Sparta promised to form an alliance for the defense of Greece. Darius’ response to this diplomatic outrage was to launch a naval force of 600 ships and 25,000 men to attack the Cyclades and Euboea, leaving the Persians just one step away from the rest of Greece. In 490 BCE Greek forces led by Athens met the Persians in battle at Marathon and defeated the invaders. The battle would take on mythical status amongst the Greeks, but in reality it was merely the opening overture of a long war with several other battles making up the principal acts. Persia, with the largest empire in the world, was vastly superior in men and resources and now these would be fully utilized for a full-scale attack.

In 486 BCE Xerxes became king upon the death of Darius and massive preparations for an invasion was made. Depots of equipment and supplies were laid, a canal dug at Chalkidiki, and boat bridges built across the Hellespont to facilitate the movement of troops. Greece was about to face its greatest ever threat, and even the oracle at Delphi ominously advised the Athenians to ‘fly to the world’s end’.

THE PASS OF THERMOPYLAE

When news of the invading force reached Greece, the initial Greek reaction was to send a force of 10,000 hoplites to hold a position at the valley of Tempē near Mt. Olympos, but these withdrew when the massive size of the invading army was revealed. Then after much discussion and compromise between Greek city-states, suspicious of each other’s motives, a joint army of between 6,000 and 7,000 men was sent to defend the pass at Thermopylae through which the Persians must enter to access mainland Greece. The Greek forces included 300 Spartans and their helots with 2,120 Arcadians, 1,000 Lokrians, 1,000 Phokians, 700 Thespians, 400 Corinthians, 400 Thebans, 200 men from Phleious, and 80 Mycenaeans.

The relatively small size of the defending force has been explained as reluctance by some Greek city-states to commit troops so far north, and/or due to religious motives, for it was the period of the sacred games at Olympia and the most important Spartan religious festival, the Karneia, and no fighting was permitted during these events. Indeed, for this very reason, the Spartans had arrived too late at the earlier battle of Marathon. Therefore, the Spartans, widely credited as being the best fighters in Greece and the only city-state with a professional army, contributed only a small advance force of 300 hoplites (from an estimated 8,000 available) to the Greek defensive force, these few being chosen from men with male heirs.

In addition to the land forces, the Greek city-states sent a fleet of trireme warships which held position off the coast of Artemision (or Artemisium) on the northern coast of Euboea, 40 nautical miles from Thermopylae. The Greeks would amass over 300 triremes and perhaps their main purpose was to prevent the Persian fleet sailing down the inland coast of Lokris and Boeotia.

The pass of Thermopylae, located 150 km north of Athens was an excellent choice for defense with steep mountains running down into the sea leaving only a narrow marshy area along the coast. The pass had also been fortified by the local Phokians who built a defensive wall running from the so-called Middle Gate down to the sea. The wall was in a state of ruin, but the Spartans made the best repairs they could in the circumstances. It was here, then, in a 15-meter wide gap with a sheer cliff protecting their left flank and the sea on their right that the Greeks chose to make a stand against the invading army. Having somewhere in the region of 80,000 troops at his disposal, the Persian king, who led the invasion in person, first waited four days in the expectation that the Greeks would flee in panic. When the Greeks held their position, Xerxes once again sent envoys to offer the defenders the last chance to surrender without bloodshed, if the Greeks would only lay down their arms. Leonidas’ bullish response to Xerxes request was ‘molōn labe’ or ‘come and gets them’ and so battle commenced.

HOPLITES VS ARCHERS

The two opposing armies were essentially representative of the two approaches to Classical warfare – the Persians favored long-range assault using archers followed up with a cavalry charge, whilst the Greeks favored heavily-armored hoplites, arranged in a densely packed formation called the phalanx, with each man carrying a heavy round bronze shield and fighting at close quarters using spears and swords. The Persian infantry carried a lightweight (often crescent-shaped) wicker shield and was armed with a long dagger or battle-ax, a short spear, and composite bow. The Persian forces also included the Immortals, an elite force of 10,000 who were probably better protected with armor and armed with spears. The Persian cavalry was armed as the foot soldiers, with a bow and an additional two javelins for throwing and thrusting. Cavalry, usually operating on the flanks of the main battle, were used to mop up opposing infantry put in disarray after they had been subjected to repeated showers from the archers. Although the Persians had enjoyed the upper hand in previous contests during the recent Ionian revolt, the terrain at Thermopylae would better suit the Greek approach to warfare.

Although the Persian tactic of rapidly firing vast numbers of arrows into the enemy must have been an awesome sight, the lightness of the arrows meant that they were largely ineffective against the bronze-armored hoplites. Indeed, Spartan indifference is epitomized by Dieneces, who, when told that the Persian arrows would be so dense as to darken the sun, replied that in that case, the Spartans would have the pleasure of fighting in the shade. At close quarters, the longer spears, heavier swords, better armor, and rigid discipline of the phalanx formation meant that the Greek hoplites would have all of the advantages, and in the narrow confines of the terrain, the Persians would struggle to make their vastly superior numbers count.

BATTLE

On the first day, Xerxes sent his Median and Kissian troops, and after their failure to clear the pass, the elite Immortals entered the battle but in the brutal close-quarter fighting, the Greeks held firm. The Greek tactic of simulating a disorganized retreat and then turning on the enemy in the phalanx formation also worked well, lessening the threat from Persian arrows and perhaps the hoplites surprised the Persians with their disciplined mobility, a benefit of being a professionally trained army.

The second day followed the pattern of the first, and the Greek forces still held the pass. However, an unscrupulous traitor was about to tip the balance in favor of the invaders. Ephialtes, son of Eurydemos, a local shepherd from Trachis, seeking reward from Xerxes, informed the Persians of an alternative route –the Anopaia path– which would allow them to avoid the majority of the enemy forces and attack their southern flank. Leonidas had stationed the contingent of Phokian troops to guard this vital point but they, thinking themselves the primary target of this new development, withdrew to a higher defensive position when the Immortals attacked. This suited the Persians as they could now continue unobstructed along the mountain path and arrive behind the main Greek force. With their position now seemingly hopeless, and before their retreat was cut off completely, the bulk of the Greek forces were ordered to withdraw by Leonidas.

LAST STAND

The Spartan king, on the third day of the battle, rallied his small force – the survivors from the original Spartan 300, 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans – and made a  rearguard stand to defend the pass to the last man in the hope of delaying the Persians progress, in order to allow the rest of the Greek force to retreat or also possibly to await relief from a larger Greek force. Early in the morning, the hoplites once more met the enemy, but this time Xerxes could attack from both front and rear and planned to do so but, in the event, the Immortals behind the Greeks were late on arrival. Leonidas moved his troops to the widest part of the pass to utilize all of his men at once, and in the ensuing clash, the Spartan king was killed. His comrades then fought fiercely to recover the body of the fallen king. Meanwhile, the Immortals now entered the fray behind the Greeks who retreated to a high mound behind the Phokian wall. Perhaps at this point, the Theban contingent may have surrendered (although this is disputed amongst scholars). The remaining hoplites now trapped and without their inspirational king, were subjected to a barrage of Persian arrows until no man was left standing. After the battle, Xerxes ordered that Leonidas’ head be put on a stake and displayed at the battlefield. As Herodotus claims in his account of the battle in book VII of The Histories, the Oracle at Delphi had been proved right when she proclaimed that either Sparta or one of her kings must fall.

rearguard stand to defend the pass to the last man in the hope of delaying the Persians progress, in order to allow the rest of the Greek force to retreat or also possibly to await relief from a larger Greek force. Early in the morning, the hoplites once more met the enemy, but this time Xerxes could attack from both front and rear and planned to do so but, in the event, the Immortals behind the Greeks were late on arrival. Leonidas moved his troops to the widest part of the pass to utilize all of his men at once, and in the ensuing clash, the Spartan king was killed. His comrades then fought fiercely to recover the body of the fallen king. Meanwhile, the Immortals now entered the fray behind the Greeks who retreated to a high mound behind the Phokian wall. Perhaps at this point, the Theban contingent may have surrendered (although this is disputed amongst scholars). The remaining hoplites now trapped and without their inspirational king, were subjected to a barrage of Persian arrows until no man was left standing. After the battle, Xerxes ordered that Leonidas’ head be put on a stake and displayed at the battlefield. As Herodotus claims in his account of the battle in book VII of The Histories, the Oracle at Delphi had been proved right when she proclaimed that either Sparta or one of her kings must fall.

Meanwhile, at Artemision, the Persians were battling the elements rather than the Greeks, as they lost 400 triremes in a storm off the coast of Magnesia and more in a second storm off Euboea. When the two fleets finally met, the Greeks fought late in the day and therefore limited the duration of each skirmish which diminished the numerical advantage held by the Persians. The result of the battle was, however, indecisive and on news of Leonidas’ defeat, the fleet withdrew to Salamis.

THE AFTERMATH

The battle of Thermopylae, and particularly the Spartan’s role in it, soon acquired mythical status amongst the Greeks. Free men, in defiance of their own laws, had sacrificed themselves in order to defend their way of life against foreign aggression. As Simonedes’ epitaph at the site of the fallen stated: ‘Go tell the Spartans, you who read: We took their orders and here lie dead’.

A glorious defeat maybe, but the fact remained that the way was now clear for Xerxes to push on into mainland Greece. The Greeks, though, were far from finished, and despite many states now turning over to the Persians and Athens itself being sacked, a Greek army led by Leonidas’ brother Kleombrotos began to build a defensive wall near Corinth. Winter halted the land campaign, though, and at Salamis, the Greek fleet maneuvered the Persians into shallow waters and won a resounding victory. Xerxes returned home to his palace at Sousa and left the gifted general Mardonius in charge of the invasion. After a series of political negotiations, it became clear that the Persians would not gain victory through diplomacy and the two armies met at Plataea in August 479 BCE. The Greeks, fielding the largest hoplite army ever seen, won the battle and finally ended Xerxes’ ambitions in Greece.

As an interesting footnote: the important strategic position of Thermopylae meant that it was once more the scene of battle in 279 BCE when the Greeks faced invading Gauls, in 191 BCE when a Roman army defeated Antiochus III, and even as recent as 1941 when Allied New Zealand forces clashed with those of Germany.

Meteora:

Meteora is an exquisite complex that consists of huge dark stone pillars rising outside Trikala, near the mountains of Pindos. The monasteries that sit on top of these rocks make up the second most important monastic community in Greece, after Mount Athos in Halkidiki. Out of the thirty monasteries that were founded throughout the centuries, only six of them are active today.

The history of Meteora goes back to many millenniums. Theories on the creation of this natural phenomenon are associated with the geological movements that occurred over several geological periods. Scientists believe that these pillars were formed about 60 million years ago, during the Tertiary Period. At the time, the area was covered by sea but a series of earth movements caused the seabed to withdraw. The mountains left were continuously hit by strong winds and waves, which, in combination with extreme weather conditions, affected their shape, leaving us with pillars composed of sandstone and conglomerate. In the Byzantine times, monks had the inspiration to construct monasteries on top of these rocks so that they would be closer to god.

The history of Meteora goes back to many millenniums. Theories on the creation of this natural phenomenon are associated with the geological movements that occurred over several geological periods. Scientists believe that these pillars were formed about 60 million years ago, during the Tertiary Period. At the time, the area was covered by sea but a series of earth movements caused the seabed to withdraw. The mountains left were continuously hit by strong winds and waves, which, in combination with extreme weather conditions, affected their shape, leaving us with pillars composed of sandstone and conglomerate. In the Byzantine times, monks had the inspiration to construct monasteries on top of these rocks so that they would be closer to god.

The foundation of Meteora monasteries began around the 11th century. In the 12th century, the first ascetic state was officially formed and established a church to the Mother our Lord as their worshiping center. Activities of this church were not only related to worshiping God, but hermits used these occasions to discuss their problems and exchange ideas relating their ascetic life there. In the 14th century, Saint Athanasios established the Holy Monastery of the Transfiguration of Jesus and named this huge rock Meteoro, which means hanged from nowhere. This monastery is also known as the Holy Monastery of the Great Meteoron, the largest of all monasteries.

For many centuries, the monks used scaffolds for climbing the rocks and getting supplies. As years passed, this method was followed by the use of nets with hooks and rope ladders. Sometimes a basket was used, which was pulled up by the monks. Wooden ladders of 40 meters long were also one of the essential tools for accessing the monasteries. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, Meteora was at its prime with the arrival of many monks from other monasteries or people who wanted to lead an ascetic life in this divine environment. However, the prosperity of Meteora during that time started to fade away after the 17th century mainly due to the raids of thieves and conquerors. These caused many monasteries to be abandoned or destructed. Today, only 6 monasteries operate with a handful of monks each. The only nunnery (female monastery) is the Monastery of Agios Stefanos.

Dodoni:

The sanctuary of Dodoni was a major spiritual area in ancient Greece. It was the oldest of the Greek oracles and ancient people traveled great distances in order to consult the priests who foretold the future. Outside the temple of Zeus, the priests gathered under the sacred Oak tree and listened to the sound of the leaves as they shivered in the breeze and glimpsed in the future. People from the entire known world would make the pilgrimage in ancient times in order to consult the future-telling Oak tree and to attend cultural festivals that took place regularly at Dodoni. The Oracle is located at the foot of the majestic twin peaks of Mt. Tomaros (1972 m and 1816 m tall), and while the entire site is sprinkled with ancient ruins, the visually imposing theatre dominates the landscapes. The limestone seats appear weather-beaten and nested in a respectful semicircle between the two enormous retaining walls.

The theatre was host to theatrical plays in ancient Greece, and it was most certainly modified by the Romans at a later date to accommodate their gladiatorial games that required a semi-circular orchestra and some protection of the front row seats from the happenings in the orchestra. The rest of the Dodoni site is not as visually exciting as the theater since only the rectangular foundations of the buildings remain to outline an enormous complex of temples, hostels, granaries, and other buildings. Ask for the free brochure when you get the ticket to make some sense and orient yourself in the ruins. Dodoni is a complex archaeological site because it remained a vital center from about 2000 BCE and flourished well into the Roman times. Thus there are many layers of history that the archaeologists have been excavating. As a religious sanctuary, Dodoni was adorned with all the riches that ancient people could afford, and excavations have unearthed a multitude of artifacts that date back to archaic times. None of it remains on the site of course. Most of the important findings are housed at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, while some reside in the Archaeological museum at Ioannina, both of which are well worth a visit.

Dodoni is a small archaeological site out of the main path of most tourists. As such, it’s a quiet place, with few groups and individuals strolling about the ruins.

Aigai (Vergina):

To the south of River Haliacmon, in the “land of the Macedon”, as described by Herodotus, on the foothills of Pieria, the ancient “Macedonian mount”, lays Aigai, the first city of the Macedon, the land with many goats (“Aigai” in ancient Greek means “goats”). Aigai was a city formed by distinct villages, an “open” city having a central core and multiple settlements of various sizes developing around it. This multiplicity explains the plural suffix of its name (the diphthong “ai”).

In the mid-7th century BCE, Perdiccas I, a Dorian from Argos, a descendant, according to tradition, of the family of Hercules, became king of Macedonians. Aigai became the cradle of the Temenids, the dynasty that would rule Macedonia for 3.5 centuries and, give to humanity Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, who set off from Aigai and changed the history of Greece and the world.

In the mid-7th century BCE, Perdiccas I, a Dorian from Argos, a descendant, according to tradition, of the family of Hercules, became king of Macedonians. Aigai became the cradle of the Temenids, the dynasty that would rule Macedonia for 3.5 centuries and, give to humanity Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, who set off from Aigai and changed the history of Greece and the world.

The royal burials unearthed in the rich necropolis of Aigai verify the city’s prosperity. During the reign of Alexander I (498 – 454 BCE), Aigai became the center of the most significant Greek state in the north. During Archelaus reign (413 – 399 BCE), the court of Aigai was turned into hospitable heaven for great artists. The famous painter Zeuxis would decorate the king’s new palace, and Euripides would write his last tragedies here.

Macedonia and Aigai bloomed, after Philip II came to the throne he gathered around him the cream of the intelligentsia, turning his court into the model of cultural development, as Athens of Pericles once used to be. Philip II was the driving force behind the vast building project aiming at reviving Aigai, which resulted in a complete transformation of the city.

In the first half of the 4th century BCE, all kinds of political and military developments force the king of Macedon and his family to stay more in Pella, the port to the north of the Thermaic Gulf that was rapidly growing into a city. However, Aigai continued to be the traditional center, the land where kings choose to build their palaces and bury their dead, the place that hosted all major sacred ceremonies and city feasts of the kingdom.

In the summer of 336 BCE, Philip II, the elected leader, and commander of all the Greeks decided to celebrate in Aigai his supremacy by organizing an unprecedented in glory feast. The moment he entered the theatre, following the sacred procession, an assassin’s dagger struck and killed him in front of the gathered crowd. Alexander was proclaimed king after burying his father in the royal necropolis of Aigai in an unparalleled glorious ceremony.

At the beginning of the spring of 334 BCE, the young king will set forth from Aigai on the great campaign that will turn him into the ruler of the world. Alexander would hand down to the Hellenistic world the new trends and currents that arose in the environment of Philip II and will set the foundations of a new world.

The history of the world was changed, but the old seat of royalty was left to the margin. Following the fate of the kingdom, the city of Aigai was destroyed after the defeat by the Romans in 168 BCE and then fell into decline and was gradually forgotten. Until, in 1977, Manolis Andronikos excavated the site, gave it back its name and the history of Macedonia began to be rewritten.

Thessaloniki:

The Foundation

The city of Thessaloniki Greece was founded in 315 BCE by king Cassander of Macedonia. It got its name from Thessaloniki, wife of Cassander and half-sister of Alexander the Great, who, in turn, was named like that after her father, King Phillip II of Macedonia, to commemorate his victory over the Phocians with the help of Thessalian horsemen. Thessaloniki, in Greek, actually means the “victory of the Thessalians”.

Roman Times

Soon it became an important urban center because of its location, it got fortified and after the Romans had conquered Greece, in the 2nd century BCE, it became the capital of one of the four Roman districts of Macedonia. The Romans built a spacious harbor and set the foundations for the flourishing city. In the 1st century AD, Thessaloniki got a Jewish community. Later on, the  Apostle Paul would preach in the Jewish synagogue, establish a Christian church and write two letters to the Christian community of the city, known as the Epistles to the Thessalonians.

Apostle Paul would preach in the Jewish synagogue, establish a Christian church and write two letters to the Christian community of the city, known as the Epistles to the Thessalonians.

Byzantine Period

Later during the Byzantine Era, after Constantinople was made the capital of the Byzantine Empire, Thessaloniki would progressively turn into the second largest city of the whole Empire. The population started to increase and trade was the main occupation of its residents. Unfortunately, a severe earthquake in 620 AD damaged the Roman market and many buildings. However, the city managed to recover in the decades that followed. In the seventh century, the Slavs tried to occupy Thessaloniki but they failed. To prevent such an attack again, the Byzantines tried another strategy: the Byzantine Emperor Michael III sent the brothers Cyril and Methodium, who were born in Thessaloniki and later were declared saints of the Greek Orthodox Church, to teach the Slavs the Christian religion. In 904 AD, the Saracen pirates of Crete attacked the city and took 22,000 people as slaves. In 1204, after the Crusaders had conquered Constantinople, they also conquered Thessaloniki. However, the Byzantines managed to gain it back in 1246. It is actually remarkable how Thessaloniki, through all this hassled period, managed to maintain a large population and flourishing commerce. The churches of that period, their frescoes and the scripts of some scholars illustrate an intellectual and artistic development.

Ottoman occupation

The Byzantine Emperors of the early 15th century were unable to protect the city from the Ottoman Empire and sold it to the Venetians. However, the Ottomans managed to siege Thessaloniki in 1430. They reformed the Castle and built many mosques and baths, some of which survive till today. Although the city suffered five centuries of Turkish occupation, its development didn’t stop and people would take advantage of the Ottoman reforms. The population continued to increase and consisted of Greek Orthodox people, Muslims, and Jews.

Liberation

Thessaloniki was set free from the Turks on October 27th, 1912, during the First Balkan War. King George I of Greece settled in Thessaloniki to stress the Greek possession of the city and was murdered near the White Tower in March 1913. In 1916, in the middle of World War I, Eleftherios Venizelos, the Greek prime minister, launched the Movement of National Defense, formed a new government and made Thessaloniki the capital of the Greek state, to show both his disagreement with the pro-German king of Greece and also Greece’s support to the Allied forces.

Recent times

In 1941, during World War II, the Nazi Troops entered the city and their occupation lasted until 1944. Their bombs destroyed a large part of the city and most of the Jewish population was slaughtered. When the war ended, the city was rebuilt and became a modern European city. Industry and trade developed in the decades that followed. On June, 20th, 1978, an earthquake of 6.5 degrees on the Richter scale destroyed many buildings, even some Byzantine monuments, and killed forty people. Once again, Thessaloniki managed to recover. In 1988, the Early Christian and Byzantine sites of Thessaloniki were declared by UNESCO as World Heritage Monuments and in 1997, it became the European City of Culture. Today, Thessaloniki is a modern city with a flourishing economy and a strong connection to its glorious past, through the many ancient sites around the city.

Pella:

At the center of a series of satellite settlements, with a “territory” that extended as far as the quarries of Kyrrhos, the former Lake Loudias, Platanopotamos and the gulley of Yanitsa, Pella was fortified from the time of Philip II, the ruler who transformed it into a city of international (for the period) influence, and was the most important city in south-eastern Bottiaia, a region enclosed by the Axios and the Haliakmon and bounded by the mountain ranges of Berman and Paikon. The surrounding area was inhabited from as early as the Neolithic Period (about 16 settlements have been located) and had a large number of sites in the Bronze Age. The local inhabitants-colonists form Crete, according to tradition-were displaced by the Makedones when the latter crossed from Pieria to the vast pasturages in the modern counties of Emathia and Pella.

Pella was already known to Hekataios, Herodotus and Thucydides (5th century B.C.E.); at the beginning of the fourth century, has become the capital of the Macedonian kingdom at the wish of Archelaos I, it was known as “the greatest of the cities in Macedonia”. Figures like Euripides and Agathon were invited here. Here, too, men like Timotheos and Choirilos were entertained in the royal residence, and Zeuxis, one of the greatest painters of antiquity, worked here. The birthplace of Philip II, it increased in size under his reign and was adorned with a large palace. Attracted by the new regime, artists, poets, and philosophers found at the royal court a warm supporter of the arts and a generous Maecenas. At the time of Cassander, the city was extended according to the “Hippodameian” system and acquired splendid public buildings and spacious private houses with mosaic floors and fine wall paintings. It now occupied an area of about 2,500,000 sq.m. and was defended by a fortification wall, with a circuit of around 8,000 m. Initially a coastal site, it was already by the Classical period at the innermost recess of a lake formed by the alluvial deposits carried by the river Loudias, though it continued to be an important harbor since the latter waterway was navigable. A small island in the swamp, called Phakos, communicated with the city by a wooden bridge, and was used at one and the same time as a gaol and the treasury of the Macedonian state (gaza).

Pella was already known to Hekataios, Herodotus and Thucydides (5th century B.C.E.); at the beginning of the fourth century, has become the capital of the Macedonian kingdom at the wish of Archelaos I, it was known as “the greatest of the cities in Macedonia”. Figures like Euripides and Agathon were invited here. Here, too, men like Timotheos and Choirilos were entertained in the royal residence, and Zeuxis, one of the greatest painters of antiquity, worked here. The birthplace of Philip II, it increased in size under his reign and was adorned with a large palace. Attracted by the new regime, artists, poets, and philosophers found at the royal court a warm supporter of the arts and a generous Maecenas. At the time of Cassander, the city was extended according to the “Hippodameian” system and acquired splendid public buildings and spacious private houses with mosaic floors and fine wall paintings. It now occupied an area of about 2,500,000 sq.m. and was defended by a fortification wall, with a circuit of around 8,000 m. Initially a coastal site, it was already by the Classical period at the innermost recess of a lake formed by the alluvial deposits carried by the river Loudias, though it continued to be an important harbor since the latter waterway was navigable. A small island in the swamp, called Phakos, communicated with the city by a wooden bridge, and was used at one and the same time as a gaol and the treasury of the Macedonian state (gaza).

Having experienced its last decades of glory with Philip V and Perseus, Pella surrendered to the Roman general Aemilius Paulus, who encamped beneath its walls-its stout fortification walls-after his triumph at Pied in 168 BCE Headquarters of the third of the four maids (administrative districts) into which Macedonian was divided between 167 and 147 BCE, it continued, thanks to the Via Agnate, to be, like Bore, one of the “most illustrious” cities of Macedonian even after the dissolution of the Macedonian kingdom. It quickly lost its position to Thessaloniki, however, which was chosen as the capital of the Roman province in the East. Earthquakes, the occupation of the city by the armies of Mithridates VI, the major economic crisis of this period, and above all the foundation (probably in 150 B.C.E.) of the Colonia Pellensis– that is, the Roman colony of Pella-to the west, on the site of the modern community of Nea Pella, all brought an end to the city that had seen the armies of Alexander the Great pass before it on their way to the conquest of Asia: Dio Chrysostom was to write, indicatively, at the turn of the 1st to the 2nd century A.D. that in his time all that remained of (Hellenistic) Pella was a great quantity of broken roof tiles scattered over the site. Under Diocletian, the colony was probably named Diocletianopolis, though the old name Pella soon came back into vogue. In A.D. 473, Theoderic the Goth settled with his armies in the fertile area to the west of the Axios, and the Drougoubitai, a Slav tribe, dwelt for a time in the area around Pella (7th century). A settlement seems to have survived until the end of the Byzantine period. In the Ottoman occupation, the ruins of the Hellenistic city and the Roman colony formed an ideal source of building material for the holy city of the conquerors, Yanitsa; clearly the East taking revenge for its conquest by Alexander. Though it may also be the fate of all ancient cities as they are transformed by time into the past.

The first excavation of the site, by Professor G. Oikonomou in the summer of 1914, directly after the liberation of Macedonia from the Turks, was followed four decades later by the systematic investigation of it by the Archaeological Service, which still continues to uncover the rich secrets of the city that once controlled the fortunes of the then known world. At the edge of the former lake of Yanitsa, the poor settlement of Ayioi Apostoloi will acquire a new name, and the place will rediscover its former glory.

The City

Little is known of the pre-Cassandreian city. The larger part of the inhabited area, as well as the cemetery dating from the first half of the 4th century B.C.E., appear to have been razed during the laying-out of Cassander’s ambitious urban design. To the time of Philip II, however, belong a number of cist graves to the east, and possibly also the main part of the palace on the so-called acropolis. The grid used in post-Alexandrian Pella consists of two sets of straight, parallel streets, intersecting at right angles to form rectangular blocks of buildings. In this system, known as the “Hippodameian” plan, the short side of the rectangle is invariably 47 m. The long side (north-south), in contrast, varies in a set pattern (125, 111, 125, 150, 125 m. etc.). The width of the streets running through the city from east to west is about 9 m., that of that oriented north-south about 6 m.

The Agora

This area, of great importance in every ancient city, is integrated harmoniously into the urban tissue, covering five building blocks in an east-west direction. It is narrower on the south, to allow the creation of five small blocks of buildings that were given over to commercial establishments and workshops. With dimensions of roughly 200 m. x 182 m., the main area of the Agora, together with the stoas encircling it, and the shops on the sides, formed a building complex of imposing scale. A broad avenue, 15 m. wide, started in the center of it and ran to east and west through the entire width of the city, connecting it with Edessa in one direction and Thessalonike in the other. The construction of the Agora in the form known today is probably not much earlier than the last quarter of the 3rd century B.C.E., and may well date from the early years of the reign of Philip V. The complex was destroyed, either by an earthquake or by the raids of barbarian Thracian tribes, probably in the first twenty years of the 1st century B.C.E.

The houses

Following the articulation typical of the ancient Greek house, the private residence at Pella in the late Classical period has a distinctly introverted character. The plain, undecorated exterior stands in contrast to the interior of the rooms, arranged around a square courtyard, with their richly decorated walls and multi-colored mosaic floors. Two types of the house have been identified in the Macedonian capital: one with an interior peristyle, and one with a pastas (a kind of portico). The rooms in daily use and the rooms for the reception of guests were on the northern side, which was usually two-storeyed, while the store-rooms and the ancillary areas, in general, were grouped on the south side.

One of the wealthier houses with a peristyle, the House of Dionysos, with its brilliant mosaic floors depicting Dionysos riding on a panther, and a Lion Hunt, has two internal peristyle courtyards. An equally spacious house is that with mosaic floors depicting a Deer Hunt, the Abduction of Helen by Theseus, and the fragmentary scene of an Amazonomachy. Breaking new ground in their conception, the mosaics of Pella, with their subtle use of foreshortening and chiaroscuro, successfully convey a feeling of three-dimensional space. Their technique is more advanced than that of the mosaic floors of Olynthos, and their main features are the use of alternating colors, and of fine strips of clay or lead to picking out detail; the representational scenes, whether used as the main motifs-as “paintings’ adorning the andrones(banquet rooms)- or as decoration for the thresholds of the anterooms, are brilliant examples of painting from antiquity.

The residences of post-Alexandrian Pella were costly structures, reflecting the wealth that flowed into Macedonia on the morrow of the campaign in Asia and form points of reference for urban architecture in later centuries.

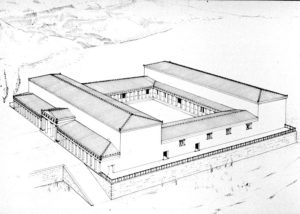

The Palace

Occupying the entire extent of the hill dominating ancient Pella on the north side of the city, the palace complex of the Macedonian kingdom has an area of 60,000 sq. m. Articulated into three independent though interconnected units set side by side, the overall complex of buildings is integrated harmoniously into an urban grid that consists of vertical and horizontal zones. Each one of these building units is articulated around a central courtyard, around which are set roofed residential areas. The central unit is an exception since it includes two open peristyle areas. Along the entire south side, the complex takes the form of a veranda (belvedere) of impressive size, from which the residents, high, gazed upon the boundless plain and even the Thermaic Gulf, with the city spreading immediately in front of them. Fragments of doric and ionic columns of various diameters suggest that there was an upper storey on some of the wings of the building complex also had a swimming pool.

The successive building phases detected during the excavation of the area undoubtedly make it difficult to define precisely the chronological sequence of the structures. However, on the basis of certain data, it seems fairly sure that the central part of the complex belonged to the end of the first half of the 4th century B.C.E. Modifications, additions and repairs were carried out mainly during the second half of this same century and throughout the 3rd.

The Cemeteries

The earliest tombs in the area that is now the site of the ancient Agora were individual graves cut into the soft limestone of the region, dating from the last quarter of the 5th to the third quarter of the 4th century. They gave way to built cist graves in an area to the east of Pella (middle to end of the 4th century B.C.E.) and to family vaulted rock-cut chamber tombs that survived the Roman conquest. The rich grave offerings-vases, jewelry, decorative attachments for wooden funerary furniture, metal objects, etc. – adorn the display cases of the local Museum and attest both to the piety of the inhabitants of the Macedonian kingdom towards their dead, and to the prosperity of the city.

Cults

To the gods, heroes and demons known from the literary and epigraphic traditions (Great Gods, Herakles Phylakos and Asklepios), excavation has added the sanctuaries of Demeter (Thesmophorion), Cybele, Aphrodite and Darron, and has indicated the existence of cults of Poseidon, Dionysos, Athena, with the epithet Alkidemos, and Pan.

Dion:

The ancient city owes its name to the most important Macedonian sanctuary dedicated to Zeus (Dios, “of Zeus”), leader of the gods who lived on Mount Olympus. Thyia and daughter of Deucalion bore Zeus two sons, Magnes and Makednos, eponym of Macedonians, who settled in Pieria at the foot of Mount Olympus. So on the foothills of Mt. Olympos, only 5 km. from the Pierian shores lay the city of ancient Dion which contains a number of Greek- and Roman-era ruins. Today it operates as an archaeological site and museum. At the site extensive archaeological excavations have been conducted by the University of Thessaloniki (under Professor D. Pandermalis) to discover the sacred city of the Macedonians.

Dion became the religious center of the Macedonian kingdom in the 5th century BCE as well as hosting important games. They used to gather to honor the Olympian gods with sacrifices and offerings. Especially at the Sanctuary of Olympian Zeus inscriptions were set up referring to important state affairs such as peace treaties, regulation of boundaries, honorary announcements, etc. The Macedonians who crowded these festivals could read these texts and be informed.

King Archelaos (414 – 399 BCΕ) brightened these festivals with nine days of games that included athletic and dramatic competitions in honor of Zeus, whose organization was overseen by the Macedonian kings themselves. There Philip II celebrated his glorious victories. In the 4th century BCE, Alexander the Great offered sacrifices at the Temple of Olympian Zeus, in Dion, before setting out on his campaign against the Persian Empire. He later donated a magnificent statue to the temple, portraying his fallen cavalry troops who had died at the Battle of Granicus. Heavily damaged by Aetolian invaders in 219 BCΕ, the city was rebuilt and survived into the Roman era – Emperor Augustus founded a Roman colony there in 31 BCΕ.

However, as the Empire weakened the threat of barbarian attack combined with natural disasters and slowly the city was abandoned. Though it survived into Byzantine times, there is no reference to ancient Dion after the 10th century AD.

Architecture

Today Dion Archaeological Site is located just outside the modern town and contains a number of interesting ruins from the Greek and Roman periods. Chief among these are the many Greek temples, including the large Temple of Zeus as well as temples to Demeter, Isis, and Asclepius. These include the oldest known holy structures of the Macedonians, two small temples of the “megaron” type that is a building with an open antechamber and a cella. Located just outside (southeast corner of) the city wall is another great find the intact sanctuary of Isis which was succeeded by Artemis. Ancient Dion was a well laid-out city. A sophisticated network of roads, paved during Imperial times, separated the housing and allowed the free circulation of pedestrians and vehicles. Fourteen roads have been located. The site also contains the remains of a Hellenistic theatre, a partly-preserved 2nd century AD Roman theatre, ancient baths and the ruins of several ancient villas with beautiful mosaics. A rare and unusual find in the museum is a bronze “hydraulis” or hydraulic musical pipe organ and in 2006, a statue of Hera was found built into the walls of the city. The statue, 2200 years old, had been used by the early Christians of Dion as filling for the city’s defensive wall. A later-Roman church can also be found here, probably dating to the 4th or 5th centuries AD. Among Dion’s other treasures is an extremely well preserved Macedonian tomb.

Dion Archaeology Museum operates at the site and contains a fascinating selection of artifacts found within the ruins.

Delphi:

Delphi was an important ancient Greek religious sanctuary sacred to the god Apollo. Located on Mt. Parnassus near the Gulf of Corinth, the sanctuary was home to the famous oracle of Apollo which gave cryptic predictions and guidance to both city-states and individuals. In addition, Delphi was also home to the PanHellenic Pythian Games.

MYTHOLOGY & ORIGINS:

The site was first settled in Mycenaean times in the late Bronze Age (1500-1100 BCE) but took on its religious significance from around 800 BCE. The original name of the sanctuary was Pytho after the snake which Apollo was believed to have killed there. Οfferings at the site from this period include small clay statues (the earliest), bronze figurines, and richly decorated bronze tripods.

Delphi was also considered the center of the world, for in Greek mythology Zeus released two eagles, one to the east and another to the west, and Delphi was the point at which they met after encircling the world. This fact was represented by the omphalos (or navel); a dome-shaped stone which stood outside Apollo’s temple and which also marked the spot where Apollo killed the Python.

APOLLO’S ORACLE:

The oracle of Apollo at Delphi was famed throughout the Greek world and even beyond. The oracle – the Pythia or priestess – would answer questions put to her by visitors wishing to be guided in their future actions. The whole process was a lengthy one, usually taking up a whole day and only carried out on specific days of the year. First, the priestess would perform various actions of purification such as washing in the nearby Castalian Spring, burning laurel leaves and drinking holy water. Next an animal – usually a goat – was sacrificed. The party seeking advice would then offer a pelanos – a sort of pie – before being allowed into the inner temple where the priestess resided and gave her pronouncements, possibly in a drug or natural gas-induced state of ecstasy.

Perhaps the most famous consultant of the Delphic oracle was Croesus, the fabulously rich King of Lydia who, when faced with a war against the Persians, asked the oracle’s advice. The oracle stated that if Croesus went to war then a great empire would surely fall. Reassured by this, the king took on the mighty Cyrus. However, the Lydians were overpowered at Sardis and it was the Lydian empire which fell, a lesson that the oracle could easily be misinterpreted by the unwise or over-confident.

PANHELLENIC GAMES:

Delphi, as with the other major religious sites of Olympia, Nemea, and Isthmia, held games to honor various gods of the Greek religion. The Pythian Games of Delphi began sometime between 591 and 585 BCE and were initially held every eight years, with the only event being a musical competition where solo singers accompanied themselves on a kithara to sing a hymn to Apollo. Later,  more musical contests and athletic events were added to the program, and the games were held every four years with only the Olympic Games being more important. The principal prize for victors in the games was a crown of laurel or bay leaves.

more musical contests and athletic events were added to the program, and the games were held every four years with only the Olympic Games being more important. The principal prize for victors in the games was a crown of laurel or bay leaves.

The site and games were managed by the independent Delphic amphictiony – a council with representatives from various nearby city-states – which asked for taxes, collected offerings, invested in construction programs, and even organized military campaigns in the Four Sacred Wars, fought to remedy sacrilegious acts against Apollo committed by the states of Crisa, Phocis, and Amphissa.

ARCHITECTURE:

The first temple in the area was built in the 7th century BCE and was a replacement for less substantial buildings of worship which had stood before it. The focal point of the sanctuary, the Doric temple of Apollo, was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 548 BCE. A second temple, again Doric in style, was completed in 510 BCE. Measuring some 60 by 24 meters, the facade had six columns whilst the sides had 15. This temple was destroyed by an earthquake in 373 BCE and was replaced by a similarly sized temple in 330 BCE. This was constructed with poros stone coated in stucco. Marble sculpture was also added as decoration along with Persian shields taken at the Battle of Marathon. This is the temple which survives, although only partially, today.

Other notable constructions were the theatre (with capacity for 5,000 spectators), temples to Athena (4th century BCE), a tholos with 13 Doric columns ( 580 BCE), stoas, a stadium (with capacity for 7,000 spectators), and around 20 treasuries, which were constructed to house the votive offerings and dedications from city-states all over Greece. Similarly, monuments were also erected to commemorate military victories and other important events. For example, the Spartan general Lysander erected a monument to celebrate his victory over Athens at Aegospotami. Other notable monuments were the great bronze Bull of Corcyra (580 BCE), the ten statues of the kings of Argos (369 BCE), a gold four-horse chariot offered by Rhodes, and a huge bronze statue of the Trojan Horse offered by the Argives (413 BCE). Lining the sacred way, from the sanctuary gate up to the temple of Apollo, the visitor must have been greatly impressed by the artistic and literal wealth on display. Alas, in most cases, only the monumental pedestals survive of these great statues, silent witnesses to lost grandeur.

DEMISE:

In 480 BCE the Persians attacked the sanctuary and in 279 BCE the sanctuary was attacked again, this time by the Gauls. During the 3rd century BCE, the site came under the control of the Aitolian League. In 191 BCE Delphi passed into Roman hands; however, the sanctuary and the games continued to be culturally important in Roman times, in particular under Hadrian. The decree by Theodosius in 393 CE to close all pagan sanctuaries resulted in Delphi’s gradual decline. A Christian community dwelt at the site for several centuries until its final abandonment in the 7th century CE.

The site was ‘rediscovered’ with the first modern excavations being carried out in 1880 CE by a team of French archaeologists. Notable finds were splendid metope sculptures from the treasury of the Athenians (490 BCE) and the Siphnians (525 BCE) depicting scenes from Greek mythology. In addition, a bronze charioteer in the severe style (480 – 460 BCE), the marble Sphinx of the Naxians (560 BCE), the twin marble archaic statues – the kouroi of Argos (580 BCE) and the richly decorated omphalos stone (330 BCE) – all survive as testimony to the cultural and artistic wealth that Delphi had once enjoyed.

Hosios Loukas:

The World Heritage–listed monastery, Moni Osios Loukas, is 23 km southeast of Arahova, between the villages of Distomo and Kyriaki. The monastic complex includes two churches. Its principal  church contains some of Greece’s finest Byzantine frescoes. Modest dress is required (no shorts). Nearby is the smaller 10th-century Agia Panagia (Church of the Virgin Mary). The monastery is dedicated to a local hermit who was canonized for his healing and prophetic powers

church contains some of Greece’s finest Byzantine frescoes. Modest dress is required (no shorts). Nearby is the smaller 10th-century Agia Panagia (Church of the Virgin Mary). The monastery is dedicated to a local hermit who was canonized for his healing and prophetic powers

The interior of the larger church, Agios Loukas, is a glorious symphony of marble and mosaics, with icons by Michael Damaskinos, the 16th-century Cretan painter. In the main body of the church, the light is partially blocked by the ornate marble window decorations, creating striking contrasts of light and shade. Walk around the corner to find several fine frescoes that brighten up the crypt where St Luke is buried.

MARATHON BATTLEFIELD:

At Marathon, we stood alone against Persia. And our courage in that mighty endeavor defeated the men of 46 nations.

Marathon was a battle of opposites. A tiny democratic city-state opposed a despotic empire hundreds of times its size. One army was almost entirely composed of armored infantrymen, the other of horsemen and archers. This clash of cultures was profound to affect the subsequent development of Western civilization.

For the city-state was Athens, where a functioning democracy had been created just two decades previously. The previous ruler of Athens, Hippias, had fled to the court of Darius 1 (521 -486 BC), king of Persia, whose empire stretched from the Aegean Sea to the banks of the Indus. Until they were conquered by Persia, the Greek colonies in Asia Minor had been independent. Unsurprisingly, they felt a greater affinity with their former homeland of Greece than with their ruler thousands of miles away in Persia. The Greeks of Asia Minor rebelled against the Persians and were assisted by Athenian soldiers who captured and burned Sardis, the capital of Lydia, in 498. Herodotus, the historian tells us:

‘Darius enquired who these Athenians were, and on being told … he prayed “Grant to me, God, that might punish them”, and he set a slave to tell him three times as he sat down to dinner “Master, remember Athenians”.’

Marathon, some 40 km (25 miles) east of Athens. Modern research has moved the date of this landing to August from the traditional date in early September. The size of the invading force is uncertain, with some estimates as high as 100,000 men. Probably there were about 44,000 men, including oarsmen and cavalry. Marathon was chosen because it was sufficiently far from Athens for an orderly disembarkation and because the flat ground suited the Persian cavalry, which outmatched the Greek horse.

Hippias, the former tyrant of Athens, accompanied the invaders. It was hoped that his presence might inspire a coup by the conservative aristocrats of Athens and bring about a bloodless surrender.

The rest of Greece was cowed into neutrality. Even the Spartans, the foremost military power in Greece, discovered a number of pressing religious rituals which would keep them occupied for the duration of the crisis. Only Plataea, a tiny dependency of Athens, sent reinforcements to the Athenian force which mustered before the plain of Marathon, in an area called Vrana between the hills and the sea.

The Athenians had about 7,200 men. They were mostly hoplites, a term which comes from the hoplon, the large circular shield which they carried. Each shield also offered support to the soldier on the shield bearer’s left, allowing this man to use his protected right arm to stab at the enemy with his principal weapon – the long spear. The Persian infantry preferred the bow and was fearsomely adept with it. They fired from behind large wicker shields which protected them from enemy bow fire but were of doubtful value against attacking infantry.

Miltiades, the Athenian leader, knew his enemy, for he had once served in the Persian army. Now he had to convince a board of ten fellow generals that his plan of attack would succeed. Each general commanded for one day in turn and, though they ceded that command to Miltiades, he still waited until his allotted day before ordering the attack.

Miltiades, the Athenian leader, knew his enemy, for he had once served in the Persian army. Now he had to convince a board of ten fellow generals that his plan of attack would succeed. Each general commanded for one day in turn and, though they ceded that command to Miltiades, he still waited until his allotted day before ordering the attack.

This delay was probably for military rather than political reasons. To neutralize the superior Persian cavalry the Athenians might have needed to bring up abates, spiky wooden defenses, to guard their flanks. Or they might have waited for the Persian cavalry to consume their available supplies and be forced to go foraging. Or Datis, the Persian commander, might have broken the deadlock by ordering a march on Athens.The Athenians deployed most of their strength on the wings, perhaps to buffer a cavalry thrust, or so that they could extend their line to counter a Persian envelopment. This left the center dangerously weak, especially as the toughest of the Persian troops were deployed against it. They charged down the slight downhill slope at a run. The startled Persians misjudged the speed of the Athenian advance, and many of their arrows sped over the hoplites’ heads and landed harmlessly behind them.

Though caught off balance, the Persians were tough and resilient fighters. They broke the Athenian center and drove through towards Athens. But the hoplite force destroyed the wings and rolled them up in disorder before turning on the Persian regulars who had broken their center. The fight boiled through the Persian camp as the Persians struggled to regain their ships, with those who failed being driven into the marshes behind the camp.

The Athenians captured only seven ships –perhaps because the Persian cavalry belatedly reappeared. Nevertheless, it was a stunning victory. Over 6,000 Persians lay dead for the loss of 192 on the Athenian side. But there was no time for self-congratulation. The Persian fleet then started heading down the coast to where Athens lay undefended. In the subsequent race between the army on land and the army at sea, the Athenians were again victorious. On seeing the Athenian army mustered to oppose their landing, the Persians hesitated briefly, then sailed away.

Outcome:

Without a Greek victory at Marathon, Athens might never have produced Sophocles, Herodotus, Socrates, Plato or Aristotle. The word might never have known Euclid, Pericles or Demosthenes – in short, the cultural heritage of Western civilization would have been profoundly altered.

Nor would a young runner called Phaedippides have brought news of the victory to Athens. Phaedippides had earlier gone to Sparta asking for help, and now his heart gave way under the strain of his exertions. But a run of 41 km (26 miles) is still named after the battle from which he came – a marathon.

COMBATANTS:

Greeks:

10,000 men, of which 7,200 were Athenian hoplite infantrymen

Commanded by Miltiades and Callimachus, 192 dead

Persians:

45,000 – 50,000 men

Commanded by Datis, 6,400 dead (according to the Greeks)

Marathon Race History:

A race of 42,195 meters that designates the grandeur of human strength. A legend of 2.500 years, beginning with the myth of Pheidippides and reaching the modern heroes of classic sports. A race that unites millions of people in all around the world. This is what the marathon run is about and what follows is its history…

Nenikékamen, (“We have won”)

The birth of the marathon run, basically identifies with the epic Battle of Marathon, in 490 b.c. The historians talk about the transmission of the joyous announcement of the Greek victory, from Marathon to Athens, by a soldier that covered 42,195 meters, in order to get from the plain of the battle to the current Greek capital.According to the legend, this soldier was no one else but Pheidippides, the famous runner of those times, who – according to Herodotus – was assigned to run a distance of 1.140 stages (more than two hundred kilometers) in two days, in order to get from Marathon to Sparta and ask for the help of Spartans, as soon as the Persians disembarked on the Attica bay.Tradition says that, as soon as Pheidippides entered the settings of the Assembly of Parliament, he exclaimed the prominent “Nenikikamen” whereupon he promptly died of exhaustion …

No historical report, however, confirm that Pheidippides was the one who ran first the distance Marathon- Athens.

In the 1st century a.c., Ploutarchos stated that the announcement of the Greek victory, reached Athens through a simple Greek soldier, who fought in the Battle, named “Efklis”. Wearing his armor, Efklis ran 42.195 meters and in his footsteps, were meant to walk millions of people, centuries later…

The marathon in modern times:

When the modern Olympics began in 1896, the initiators and organizers were looking for a great popularizing event, recalling the ancient glory of Greece. The idea of a marathon race came from Michel Bréal, who wanted the event to feature in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 in Athens. This idea was heavily supported by Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, as well as by the Greeks. The Greeks staged a selection race for the Olympic marathon on 10 March 1896 that was won by Charilaos Vasilakos in 3 hours and 18 minutes (with the future winner of the introductory Olympic Games marathon, Spyridon “Spyros” Louis, coming in fifth). The winner of the first Olympic Marathon, on 10 April 1896 (a male-only race), was Spyridon Louis, a Greek water-carrier, in 2 hours 58 minutes and 50 seconds. The marathon of the 2004 Summer Olympics was run on the traditional route from Marathon to Athens, ending at Panathinaiko Stadium, the venue for the 1896 Summer Olympics. That Men’s marathon was won by Italian Stefano Baldini in 2 hours 10 minutes and 55 seconds.

Sounio (Temple of Poseidon):