2 days

Private Tour

English

Up to 12 Guests

2 Days Private Tour: Delphi-Mycenae & Corinth

Got a Question?

Contact UsHighlights

2 Days Historical sightseeing private tour

Day 1st:

- Levadia – Distomo

- Hosios Loukas Monastery

- Arachova

Overnight: Delphi

Day 2nd:

- Village of Delphi

- The Oracle of Delphi – Museum of Delphi

- Sanctuary Athena Pronea – Gymnasium

- Corinth Canal

- Ancient Corinth – Temple of Apollo

- Mycenae Archaeological Site

- Drive to Athens

Itinerary

1st Day:

The tour starts with a drive on the national highway towards northern Greece. Passing by the plane of Theves and the city of Levadia then we will be on the slopes of Mount Parnassus before reaching Delphi.

The tour starts with a drive on the national highway towards northern Greece. Passing by the plane of Theves and the city of Levadia then we will be on the slopes of Mount Parnassus before reaching Delphi.

Our first stop is going to be the monastery of Hosios Loukas, which represents the second golden age of Byzantine art (11th -12th century) in particular its golden mosaic decoration and fine architecture. After spending sometime in this area of serenity we will drive to the site of Delphi, an ancient Greek sanctuary with a PanHellenic character dedicated to the god Apollo.

It functioned as an Oracle and was considered ‘the naval’ the center of the world and is today a symbol of Greek cultural unity. The scenic location allows you to have a view of the Greek mountains and two more sites the Gymnasium and the secondary sanctuary of Athena Pronea. In the site, you will visit the temple of Apollo, where Pythia spoke to the oracles, the theater, and the stadium. While in the museum, you will be able to see the famous charioteer and Gold Ivory statues. After the site, we will have lunch at the modern village of Delphi with a view of the mountains of Fokis.

It functioned as an Oracle and was considered ‘the naval’ the center of the world and is today a symbol of Greek cultural unity. The scenic location allows you to have a view of the Greek mountains and two more sites the Gymnasium and the secondary sanctuary of Athena Pronea. In the site, you will visit the temple of Apollo, where Pythia spoke to the oracles, the theater, and the stadium. While in the museum, you will be able to see the famous charioteer and Gold Ivory statues. After the site, we will have lunch at the modern village of Delphi with a view of the mountains of Fokis.

Before we leave we will stop at a point known for its great view, you will see the Corinthian Sea, the port of Itea and the valley full of olive trees (olive sea) and our last destination will be the village of Arachova. A mountainous village built on a cliff 900 m above sea level very close to the Parnassus ski resort. You will have time for an evening walk and enjoy a local dinner after settling at the hotel.

Before we leave we will stop at a point known for its great view, you will see the Corinthian Sea, the port of Itea and the valley full of olive trees (olive sea) and our last destination will be the village of Arachova. A mountainous village built on a cliff 900 m above sea level very close to the Parnassus ski resort. You will have time for an evening walk and enjoy a local dinner after settling at the hotel.

2nd Day:

After spending the night at Arachova we will depart for Mycenae passing by Levadia and the city of Thebes.

After spending the night at Arachova we will depart for Mycenae passing by Levadia and the city of Thebes.

On our way, we will make a small stop at the Corinth Canal. Opened in 1892, it separates the Peloponnese peninsula from the rest of Greece and connects the Saronic Gulf to the Corinthian Sea. You will have time to walk across on a pedestrian bridge to admire the canal closer, (if you’re game,) on some days bungee jumping is an option.

Moving on we will continue to Ancient Corinth. The city dominated by the hill of Acrocorinth and the old Castle, the oldest and largest castle in southern Greece. The site located at the foot of the hill, beneath the castle, includes the Roman Agora of Corinth, the temple of the god Apollo and a small museum. Apart from its archaeological and historical interest Ancient Corinth is also one of the most popular religious destinations in Greece as this was where the Apostle Paul preached Christianity, was judged by the tribunal in the Agora and established the best organized Christian church of that period.

Moving on we will continue to Ancient Corinth. The city dominated by the hill of Acrocorinth and the old Castle, the oldest and largest castle in southern Greece. The site located at the foot of the hill, beneath the castle, includes the Roman Agora of Corinth, the temple of the god Apollo and a small museum. Apart from its archaeological and historical interest Ancient Corinth is also one of the most popular religious destinations in Greece as this was where the Apostle Paul preached Christianity, was judged by the tribunal in the Agora and established the best organized Christian church of that period.

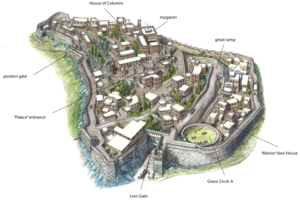

Our Next stop will be the site of Mycenae dated to the 2nd millennium BCE and representing the era of Achilles, Agamemnon, and Helen of Troy. In the site, you will see the renowned Lions Gate (the oldest architectural sculpture in Europe), the cyclopean walls, the burial circle A and the remains of Agamemnon’s Palace. Within the site, there is a modern museum exhibiting the findings of the “City Of Gold” before leaving the site we will make a small stop at the treasury of Atreus, the best-preserved Tholos tomb, one of the finest examples of the Mycenaean architecture. After that, we will head towards Athens.

Our Next stop will be the site of Mycenae dated to the 2nd millennium BCE and representing the era of Achilles, Agamemnon, and Helen of Troy. In the site, you will see the renowned Lions Gate (the oldest architectural sculpture in Europe), the cyclopean walls, the burial circle A and the remains of Agamemnon’s Palace. Within the site, there is a modern museum exhibiting the findings of the “City Of Gold” before leaving the site we will make a small stop at the treasury of Atreus, the best-preserved Tholos tomb, one of the finest examples of the Mycenaean architecture. After that, we will head towards Athens.

Inclusions - Exclusions

Private Tours are personal and flexible just for you and your party.

Inclusions:

- Professional Drivers with Deep knowledge of history. [Not licensed to accompany you in any site.]

-

Accommodation and breakfast (according to your booking)

- Hotel pickup and drop-off

- Bottled water

- Guaranteed to skip the long lines / Tickets are NOT included.

Exclusions:

- Entrance Fees

- Licensed Tour guide on request (Additional cost)

-

Accommodation and breakfast (according to your booking)

- Personal expenses (drinks, meals, etc.)

- Airport Pick Up and drop-off (Additional cost)

Entrance Fees

ADMISSION FEES FOR SITES:

Summer Period: 65€ per person

(1 April – 31 October)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Hosios Loukas Monastery: 10€ (08:00- 15:30)

Ancient Corinth: 15€ (08:00- 20:00)

Mycenae: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Winter Period: 65€ per person

(1 November – 31 March)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Hosios Loukas Monastery: 10€ (08:00- 15:30)

Ancient Corinth: 15€ (08:00- 15:30)

Mycenae: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Free admission days:

- 6 March (in memory of Melina Mercouri)

- 18 April (International Monuments Day)

- 18 May (International Museums Day)

- The last weekend of September annually (European Heritage Days)

- Every first and third Sunday from November 1st to March 31st

- 28 October

Holidays:

- 1 January: closed

- 25 March: closed

- 1 May: closed

- Easter Sunday: closed

- 25 December: closed

- 26 December: closed

Free admission for:

- Children & young people up to the age of 25 from EU Member- States

- Children & young people from up to the age of 18 from Non- European Union countries

- Persons over 25 years, being in secondary education & vocational schools from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers during the visits of schools & institutions of Primary, Secondary & Tertiary education from EU Member- States

- People entitled to Social Solidarity income & members depending on them

- Persons with disabilities & one escort (only in the case of 67% disability)

- Refugees

- Official guests of the Greek State

- Members of ICOM & ICOMOS

- Members of societies & Associations of friends of State Museums & Archaeological sites

- Scientists licensed for photographing, studying, designing or publishing antiquities

- Journalists

- Holders of a 3- year Free Entry Pass

Reduced admission for:

- Senior citizens over 65 from Greece or other EU member-states, during

the period from 1st of October to 31st of May - Parents accompanying primary education schools visits from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers of educational visits of schools & institutions of primary, secondary & tertiary education from non European Union countries

Reduced & free entrance only upon presentation of the required documents

History

Hosios Loukas:

The World Heritage-listed monastery, Moni Osios Loukas, is 23 km southeast of Arahova, between the villages of Distomo and Kyriaki. The monastic complex includes two churches. Its principal church contains some of Greece’s finest Byzantine frescoes. Modest dress is required (no shorts). Nearby is the smaller 10th-century Agia Panagia (Church of the Virgin Mary). The monastery is dedicated to a local hermit who was canonized for his healing and prophetic powers

The interior of the larger church, Agios Loukas, is a glorious symphony of marble and mosaics, with icons by Michael Damaskinos, the 16th-century Cretan painter. In the main body of the church, the light is partially blocked by the ornate marble window decorations, creating striking contrasts of light and shade. Walk around the corner to find several fine frescoes that brighten up the crypt where St Luke is buried.

Delphi:

Delphi was an important ancient Greek religious sanctuary sacred to the god Apollo. Located on Mt. Parnassus near the Gulf of Corinth, the sanctuary was home to the famous oracle of Apollo which gave cryptic predictions and guidance to both city-states and individuals. In addition, Delphi was also home to the PanHellenic Pythian Games.

MYTHOLOGY & ORIGINS:

The site was first settled in Mycenaean times in the late Bronze Age (1500-1100 BCE) but took on its religious significance from around 800 BCE. The original name of the sanctuary was Pytho after the snake which Apollo was believed to have killed there. Offerings at the site from this period include small clay statues (the earliest), bronze figurines, and richly decorated bronze tripods.

significance from around 800 BCE. The original name of the sanctuary was Pytho after the snake which Apollo was believed to have killed there. Offerings at the site from this period include small clay statues (the earliest), bronze figurines, and richly decorated bronze tripods.

Delphi was also considered the centre of the world, for in Greek mythology Zeus released two eagles, one to the east and another to the west, and Delphi was the point at which they met after encircling the world. This fact was represented by the omphalos (or navel); a dome-shaped stone which stood outside Apollo’s temple and which also marked the spot where Apollo killed the Python.

APOLLO’S ORACLE:

The oracle of Apollo at Delphi was famed throughout the Greek world and even beyond. The oracle – the Pythia or priestess – would answer questions put to her by visitors wishing to be guided in their future actions. The whole process was a lengthy one, usually taking up a whole day and only carried out on specific days of the year. First, the priestess would perform various actions of purification such as washing in the nearby Castalian Spring, burning laurel leaves and drinking holy water. Next an animal – usually a goat – was sacrificed. The party seeking advice would then offer a pelanos – a sort of pie – before being allowed into the inner temple where the priestess resided and gave her pronouncements, possibly in a drug or natural gas-induced state of ecstasy.

Perhaps the most famous consultant of the Delphic oracle was Croesus, the fabulously rich King of Lydia who, when faced with a war against the Persians, asked the oracle’s advice. The oracle stated that if Croesus went to war then a great empire would surely fall. Reassured by this, the king took on the mighty Cyrus. However, the Lydians were overpowered at Sardis and it was the Lydian empire which fell, a lesson that the oracle could easily be misinterpreted by the unwise or over-confident.

PANHELLENIC GAMES:

Delphi, as with the other major religious sites of Olympia, Nemea, and Isthmia, held games to honor various gods of the Greek religion. The Pythian Games of Delphi began sometime between 591 and 585 BCE and were initially held every eight years, with the only event being a  musical competition where solo singers accompanied themselves on a kithara to sing a hymn to Apollo. Later, more musical contests and athletic events were added to the program, and the games were held every four years with only the Olympic Games being more important. The principal prize for victors in the games was a crown of laurel or bay leaves.

musical competition where solo singers accompanied themselves on a kithara to sing a hymn to Apollo. Later, more musical contests and athletic events were added to the program, and the games were held every four years with only the Olympic Games being more important. The principal prize for victors in the games was a crown of laurel or bay leaves.

The site and games were managed by the independent Delphic amphictiony – a council with representatives from various nearby city-states – which asked for taxes, collected offerings, invested in construction programs, and even organized military campaigns in the Four Sacred Wars, fought to remedy sacrilegious acts against Apollo committed by the states of Crisa, Phocis, and Amphissa.

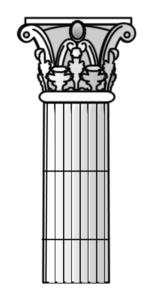

ARCHITECTURE:

The first temple in the area was built in the 7th century BCE and was a replacement for less substantial buildings of worship which had stood before it. The focal point of the sanctuary, the Doric temple of Apollo, was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 548 BCE. A second temple, again Doric in style, was completed in 510 BCE. Measuring some 60 by 24 meters, the facade had six columns whilst the sides had 15. This temple was destroyed by an earthquake in 373 BCE and was replaced by a similarly sized temple in 330 BCE. This was constructed with porous stone coated in stucco. Marble sculpture was also added as decoration along with Persian shields taken at the Battle of Marathon. This is the temple survives, although only partially, today.

Other notable constructions were the theatre (with capacity for 5,000 spectators), temples to Athena (4th century BCE), a tholos with 13 Doric columns ( 580 BCE), stoas, a stadium (with capacity for 7,000 spectators), and around 20 treasuries, which were constructed to house the votive offerings and dedications from city-states all over Greece. Similarly, monuments were also erected to commemorate military victories and other important events. For example, the Spartan general Lysander erected a monument to celebrate his victory over Athens at Aegospotami. Other notable monuments were the great bronze Bull of Corcyra (580 BCE), the ten statues of the kings of Argos (369 BCE), a gold four-horse chariot offered by Rhodes, and a huge bronze statue of the Trojan Horse offered by the Argives (413 BCE). Lining the sacred way, from the sanctuary gate up to the temple of Apollo, the visitor must have been greatly impressed by the artistic and literal wealth on display. Alas, in most cases, only the monumental pedestals survive of these great statues, silent witnesses to lost grandeur.

DEMISE:

In 480 BCE the Persians attacked the sanctuary and in 279 BCE the sanctuary was attacked again, this time by the Gauls.  During the 3rd century BCE, the site came under the control of the Aitolian League. In 191 BCE Delphi passed into Roman hands; however, the sanctuary and the games continued to be culturally important in Roman times, in particular under Hadrian. The decree by Theodosius in 393 CE to close all pagan sanctuaries resulted in Delphi’s gradual decline. A Christian community dwelt at the site for several centuries until its final abandonment in the 7th century CE.

During the 3rd century BCE, the site came under the control of the Aitolian League. In 191 BCE Delphi passed into Roman hands; however, the sanctuary and the games continued to be culturally important in Roman times, in particular under Hadrian. The decree by Theodosius in 393 CE to close all pagan sanctuaries resulted in Delphi’s gradual decline. A Christian community dwelt at the site for several centuries until its final abandonment in the 7th century CE.

The site was ‘rediscovered’ with the first modern excavations being carried out in 1880 CE by a team of French archaeologists. Notable finds were splendid metope sculptures from the treasury of the Athenians (490 BCE) and the Siphnians (525 BCE) depicting scenes from Greek mythology. In addition, a bronze charioteer in the severe style (480-460 BCE), the marble Sphinx of the Naxians (560 BCE), the twin marble archaic statues – the kouroi of Argos (580 BCE) and the richly decorated omphalos stone (330 BCE) – all survive as testimony to the cultural and artistic wealth that Delphi had once enjoyed.

Corinth Canal:

The famous Corinth Canal connects the Gulf of Corinth with the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea. It cuts through the narrow Isthmus of Corinth and separates the Peloponnesian peninsula from the Greek mainland, thus effectively making the former an island. The canal is 6.4 kilometers in length and only 21.3 meters wide at its base. Earth cliffs flanking either side of the canal reach a maximum height of 63 meters. Aside from a few modest-sized cruise ships, the Corinth Canal is unserviceable to most modern ships. The Corinth Canal, though only completed in the late 19th century, was an idea and dream that dates back over 2000 thousand years.

Before it was built, ships sailing between the Aegean and Adriatic had to circumnavigate the Peloponnese  adding about 185 nautical miles to their journey. The first to decide to dig the Corinth Canal was Periander, the tyrant of Corinth (602 BCE). Such a giant project was above the technical capabilities of ancient times so Periander carried out another great project, the diolkós, a stone road, on which the ships were transferred on wheeled platforms from one sea to the other. Dimitrios Poliorkitis, king of Macedon (c. 300 BCE), was the second who tried, but his engineers insisted that if the seas where connected, the more northerly Adriatic, mistakenly thought to be higher, would flood the more southern Aegean. At the time, it was also thought that Poseidon, the god of the sea, opposed joining the Aegean and the Adriatic. The same fear also stopped Julius Caesar and Emperors Hadrian and Caligula. The most serious try was that of Emperor Nero (67 CE). He had 6,000 slaves for the job. He started the work himself, digging with a golden hoe, while music was played. However, he was killed before the work could be completed.

adding about 185 nautical miles to their journey. The first to decide to dig the Corinth Canal was Periander, the tyrant of Corinth (602 BCE). Such a giant project was above the technical capabilities of ancient times so Periander carried out another great project, the diolkós, a stone road, on which the ships were transferred on wheeled platforms from one sea to the other. Dimitrios Poliorkitis, king of Macedon (c. 300 BCE), was the second who tried, but his engineers insisted that if the seas where connected, the more northerly Adriatic, mistakenly thought to be higher, would flood the more southern Aegean. At the time, it was also thought that Poseidon, the god of the sea, opposed joining the Aegean and the Adriatic. The same fear also stopped Julius Caesar and Emperors Hadrian and Caligula. The most serious try was that of Emperor Nero (67 CE). He had 6,000 slaves for the job. He started the work himself, digging with a golden hoe, while music was played. However, he was killed before the work could be completed.

In the modern era, the first who thought seriously to carry out the project was Kapodistrias (c. 1830), the first governor of Greece after the liberation from the Ottoman Turks. But the budget, estimated at 40 million French francs, was too much for the Greek state. Finally, in 1869, the Parliament authorized the Government to grant a private company (Austrian General Etiene Tyrr) the privilege to construct the Canal of Corinth. Work began on Mar 29, 1882, but Tyrr’s capital of 30 million francs proved to be insufficient. The work was restarted in 1890, by a new Greek company (Andreas Syggros), with a capital of 5 million francs. The job was finally completed and regular use of the Canal started on Oct 28, 1893. Due to the canal’s narrowness, navigational problems and periodic closures to repair landslips from its steep walls, it failed to attract the level of traffic anticipated by its operators. It is now used mainly for tourist traffic. The bridge above is perfect for bungee jumping.

Ancient Corinth:

Located on the isthmus which connects mainland Greece with the Peloponnese, surrounded by fertile plains and blessed with natural springs, Corinth was an important city in Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman times. Its geographical location helped it play a role as a center of, trade, naval fleet, participation in various Greek wars, and status as a major Roman colony meant the city was, for over a millennium, rarely out of the limelight in the ancient world.

CORINTH IN MYTHOLOGY

Not being a major Mycenaean center, Corinth lacks the mythological heritage of other Greek city-states. Nevertheless, the mythical founder of the city was believed to have been King Sisyphus, famed for his punishment in Hades where he was made to forever roll a large boulder up a hill. Sisyphus was succeeded by his son Glaucus and his grandson Bellerophon, whose winged-horse Pegasus became a symbol of the city and a feature of Corinthian coins. Corinth is also the setting for several other episodes from Greek mythology such as Theseus’ hunt for the wild boar, Jason settled there with Medea after his adventures looking for the Golden Fleece, and there is the myth of Arion – the real-life and gifted kithara player and resident of Corinth – who was rescued by dolphins after being abducted by pirates.

Not being a major Mycenaean center, Corinth lacks the mythological heritage of other Greek city-states. Nevertheless, the mythical founder of the city was believed to have been King Sisyphus, famed for his punishment in Hades where he was made to forever roll a large boulder up a hill. Sisyphus was succeeded by his son Glaucus and his grandson Bellerophon, whose winged-horse Pegasus became a symbol of the city and a feature of Corinthian coins. Corinth is also the setting for several other episodes from Greek mythology such as Theseus’ hunt for the wild boar, Jason settled there with Medea after his adventures looking for the Golden Fleece, and there is the myth of Arion – the real-life and gifted kithara player and resident of Corinth – who was rescued by dolphins after being abducted by pirates.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The city was first inhabited in the Neolithic period (c. 5000 BCE) but became more densely populated from the 10th century BCE. The historical founders were the aristocratic descendants of King Bacchis, the Bacchiadae (c. 750 BCE). The Bacchiadae ruled as a body of 200 until in 657 BCE when the popular tyrant Cypselus took control of the city, to be succeeded by his son Periander (627-587 BCE). Cypselus funded the building of a treasury at Delphi and set up new colonies.

From the 8th century BCE, Corinthian pottery was exported across Greece. With its innovative figure decoration, it dominated the Greek pottery market until the 6th century BCE when Attic black-figure pottery took over as the dominant style. Other significant exports were Corinthian stone and bronze wares. Corinth also became the hub of trade through the dilokos. This was a stone track with carved grooves for wheeled wagons which offered a land short-cut between the two seas and probably dates to the reign of Periander. In the Peloponnesian War, the diolkos was even used to transport triremes. Although the idea for a canal across the isthmus was first considered in the 7th century BCE and various Roman Emperors from Julius Caesar to Hadrian began surveys, it was Nero who actually began the project (67 CE). However, on the emperor’s death, the project was abandoned, not to be resumed until 1881.

From the early 6th century BCE, Corinth administered the PanHellenic games at nearby Isthmia, held every two years in the spring. These games were established in honor of Poseidon and were particularly famous for their horse and chariot races.

An oligarchy, consisting of a council of 80, gained power in Corinth (585 BCE). Concerned with the local rival, Argos, from 550 BCE Corinth became an ally of Sparta. During Cleomenes’ reign though, the city became wary of the growing power of Sparta and opposed Spartan intervention in Athens. Corinth also fought in the Persian Wars against the invading forces of Xerxes which threatened the autonomy of all of Greece.

Corinth suffered badly in the First Peloponnesian War, which it was responsible for after attacking Megara. Later it was also guilty of causing the Second Peloponnesian War, in 433 BCE. Once again though, the Corinthians, mainly as Sparta’s naval ally, had a disastrous war. Disillusioned with Sparta and concerned over Spartan expansion in Greece and Asia Minor, Corinth formed an alliance with Argos, Boeotia, Thebes, and Athens to fight Sparta in the Corinthian Wars (395-386 BCE). The conflict was fought at sea and on Corinthian territory and was yet another costly endeavor for the citizens of Corinth.

Corinth became the seat of the Corinthian League, but losing a war against Philip II of Macedon (338 BCE) this ‘honor’ was a Macedonian garrison being stationed on the Acrocorinth acropolis  overlooking the city.

overlooking the city.

A succession of Hellenistic kings took control of the city – starting with Ptolemy I and ending with Aratus in 243 BCE when Corinth joined the Achaean League. However, the worst was yet to come, when the Roman commander Lucius Mummius sacked the city (146 BCE).

A brighter period was when Julius Caesar took charge (in 44 BCE) and organized the agricultural land into organized plots (centurion) for distribution to Roman settlers. The city once more flourished, by the 1st century CE it became an important administrative and trade center again. In addition, following St. Paul’s visit between 51 and 52 CE, Corinth became the center of early Christianity in Greece. In a public hearing, the saint had to defend himself against accusations from the city’s Hebrews that his preaching undermined the Mosiac Law. The pro-consul Lucius Julius Gallio judged that Paul had not broken any Roman law and so was permitted to continue his teachings. From the 3rd century, CE Corinth began to decline and the Germanic tribes attacked the city.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

In Greek Corinth, there were cults to Aphrodite (protector of the city), Apollo, Demeter Thesmophoros, Hera, Poseidon, and Helios and various buildings to cult heroes, the founders of the city. In addition, there were several sacred springs, the most famous being Peirene. Unfortunately, the destruction in 146 BCE erased much of this religious past. In Roman Corinth, Aphrodite, Poseidon, and Demeter did continue to be worshipped along with the Roman gods.

The site today, first excavated in 1892 CE by the Greek Archaeological Service, is dominated by the Doric peripteral Temple of Apollo (550-530 BCE), originally with 6 columns on the façades and fifteen on the long sides. A particular feature of the temple is the use of monolithic columns rather than the more commonly used column drums. Seven columns remain standing today.

The majority of the other surviving buildings date from the 1st century CE in the Roman era and include a large forum, a temple to Octavia, baths, the Bema where St. Paul addressed the Corinthians, the Asklepeion temple to Asclepius, and a center of healing, fountains – including the monumental Peirine fountain complex (2nd century CE) – a propylaea, theatre, odeon, gymnasium, and stoas. There are also the remains of three basilicas.

Archaeological finds at the site include many fine mosaics – notably the Dionysos mosaic – Greek and Roman sculpture – including an impressive number of busts of Roman rulers.

Acrocorinth:

The steep rock of the Acrocorinth rises to the south-west of the ancient Corinth, surmounted by the fortress, also called the Acrocorinth, which was the fortified citadel of ancient and medieval Corinth and the most important fortification work in the area from antiquity until the Greek War of Independence in 1821. It is 575 m. high and its walls are a total of almost 2.000 m. in length.

The ascent to Acrocorinth – Acrocorinthos, is facilitated by a road which climbs to a point near the lowest rate on the W side. This commanding site was fortified in ancient times and its defenses  were maintained and developed during the Byzantine, Frankish, Turkish and Venetian periods. After a moat (alt. 380 m -1247 feet) constructed by the Venetians follow the first gate, built in the Frankish period (14th,c.) and the first wall 15th c. then come the second and third walls (Byzantine: on the right, in front of the third gate, a Hellenistic tower). Within the fortress we follow a path running NE to the remains of a mosque (16th c.) and then turn S until we join a path leading up to the eastern summit, on which there once stood the famous Temple of Aphrodite, worshipped here after the Eastern fashion (views of the hills of the Peloponnese and of Isthmus).

were maintained and developed during the Byzantine, Frankish, Turkish and Venetian periods. After a moat (alt. 380 m -1247 feet) constructed by the Venetians follow the first gate, built in the Frankish period (14th,c.) and the first wall 15th c. then come the second and third walls (Byzantine: on the right, in front of the third gate, a Hellenistic tower). Within the fortress we follow a path running NE to the remains of a mosque (16th c.) and then turn S until we join a path leading up to the eastern summit, on which there once stood the famous Temple of Aphrodite, worshipped here after the Eastern fashion (views of the hills of the Peloponnese and of Isthmus).

Courses of roughly dressed polygonal masonry allow us to suppose that the Acrocorinth was fortified as early as the time of the Kypselid tyranny (late 7th c. early 6th c. BCE). The surviving parts of the ancient fortifications, however, which are at many points beneath the medieval enceinte, belong mainly to the 4th c. BCE. In 146 BC, Mummius destroyed the fortifications of the lower city and the acropolis. The destroyed sections were subsequently reconstructed from the s During the Middle Ages, the Acrocorinth was of prime importance for the defense of the entire Peloponnese, and held out against the attacks of the barbarians. The Byzantines sporadically repaired the walls, especially after hostile raids (by the Slavs, Normans, and others), and added new fortifications on the west side of the fortress. In 1210, after a five-year siege, the Acrocorinth was captured by Otto de la Roche and Geoffroy I Villehardouin, and was incorporated in the Frankish principate of Achaea. In the middle of this century, William Villehardouin extended the fortifications of the fortress, to be followed in this by the Angevin Prince John Gravina at the beginning of the 14th c.

In 1358 the Acrocorinth passed to the Florentine banker Niccolo Acciajuoli, and in 1394 to Theodoros I Palaiologos despot of Mystras. Apart from a brief occupation by the Knights of Rhodes from 1400-1404, the fortress remained in Byzantine hands until 1458, when it was captured by the Ottoman Turks. The Venetians made themselves masters of the Acrocorinth from 1687 to 1715, after which it reverted once more to the Turks, until the Greek Uprising of 1821. The approach to the fortress is from the west side. The walls have an irregular shape, which was dictated by the form of the terrain and remained the same in general terms from the Classical period to modern times. Three successive zones of fortifications, with three imposing gateways, lead to the interior of the fortress. The fact that the same material was used for extensions or repairs to the walls frequently makes it difficult to distinguish the building phases or assign a date to them.

Mycenae:

Mycenae was a fortified late Bronze Age city located between two hills on the Argolis plain of the Peloponnese, Greece. The acropolis today dates from between the 14th and 13th century BCE when the Mycenaean civilization was at its peak of power, influence and artistic expression.

IN MYTHOLOGY:

In Greek mythology, the city was founded by Perseus, who gave the site its name either after his sword’s scabbard (mykes) fell to the ground and was regarded as a good omen or as he found a  water spring near a mushroom (mykes). Perseus was the first king of the Perseid dynasty which ended with Eurytheus (instigator of Hercules’ famous twelve labours). The succeeding dynasty was the Atreids, whose first king, Atreus, is traditionally believed to have reigned around 1250 BCE. Atreus’ son Agamemnon is believed to have been not only king of Mycenae but of all of the Achaean Greeks and the leader of their expedition to Troy to recapture Helen. In Homer’s account of the Trojan War in the Iliad, Mycenae (or Mykene) is described as a ‘well-founded citadel’, as ‘wide-wayed’ and as ‘golden Mycenae’, the latter supported by the recovery of over 15 kilograms of gold objects recovered from the shaft graves in the acropolis.

water spring near a mushroom (mykes). Perseus was the first king of the Perseid dynasty which ended with Eurytheus (instigator of Hercules’ famous twelve labours). The succeeding dynasty was the Atreids, whose first king, Atreus, is traditionally believed to have reigned around 1250 BCE. Atreus’ son Agamemnon is believed to have been not only king of Mycenae but of all of the Achaean Greeks and the leader of their expedition to Troy to recapture Helen. In Homer’s account of the Trojan War in the Iliad, Mycenae (or Mykene) is described as a ‘well-founded citadel’, as ‘wide-wayed’ and as ‘golden Mycenae’, the latter supported by the recovery of over 15 kilograms of gold objects recovered from the shaft graves in the acropolis.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW:

Situated on a rocky hill (40-50 m high) commanding the surrounding plain as far as the sea 15 km away, the site of Mycenae covered 30,000 square meters and has always been known throughout history. First excavations were begun by the Archaeological Society of Athens in 1841 and then continued by the famous Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 that discovered the magnificent treasures of Grave Circle A. The archaeological excavations have shown that the city has a much older history than traditional Greek literature described.

Even though the site was inhabited since Neolithic times, it is not until 2100 BCE that the first walls, pottery finds (including imports from the Cycladic islands) and pit and shaft graves with higher quality grave goods appear. These, collectively, suggest greater importance and prosperity in the settlement.

Since 1600 BCE there is evidence of an elite presence on the acropolis: high-quality pottery, wall paintings, shaft graves and an increase in the surrounding settlement with the construction of large tholos tombs. From the 14th century BCE the first large-scale palace complex is built (on three artificial terraces), so is the celebrated tholos tomb, the Treasury of Atreus, a monumental circular building with corbelled roof reaching a height of 13.5 m and 14.6 m in diameter and approached by a long walled and unroofed corridor 36 m long and 6 m wide. Fortification walls, of large roughly worked stone blocks, surrounding the acropolis (of which the north wall is still visible today), flood management structures such as dams, roads, Linear B tablets and an increase in pottery imports (fitting well with theories of contemporary Mycenaean expansion in the Aegean) illustrate the culture was at its zenith.

ARCHITECTURE:

The large palace structure built around a central hall or Megaron is typical of Mycenaean palaces. Other features included a secondary hall, many private rooms, and a workshop complex. Decorated stonework and frescoes and a monumental entrance, the Lion Gate (a 3 m x 3 m square doorway with an 18-ton lintel topped by two 3 m high heraldic lions and a column altar), added to the overall splendor of the complex. The relationship between the palace and the surrounding settlement and between Mycenae and other towns in the Peloponnese is much discussed by scholars. Concrete archaeological evidence is lacking but it seems likely that the palace was a center of political, religious and commercial power. Certainly, high-value grave goods, administrative tablets, pottery imports and the presence of precious materials deposits such as bronze, gold, and ivory would suggest that the palace was, at the very least, the hub of a thriving trade network.

The first palace was destroyed in the late 13th century, probably by an earthquake and then (rather poorly) repaired.  A monumental staircase, the North Gate, and a ramp were added to the acropolis and the walls were extended to include the Perseia spring within the fortifications. The spring was named after the city’s mythological founder and was reached by an impressive corbelled tunnel (or syrinx) with 86 steps leading down 18m to the water source. It is argued by some scholars that these architectural additions are evidence for a preoccupation with security and possible invasion. This second palace was also destroyed, this time with signs of fire. Some rebuilding did occur and pottery finds suggest a degree of prosperity returned briefly before another fire ended the occupation of the site until a brief revival in Hellenistic times. With the decline of Mycenae, Argos became the dominant power in the region. Reasons for the demise of Mycenae and the Mycenaean civilization are much debated with suggestions including natural disasters, over-population, internal social and political unrest or invasion from foreign tribes.

A monumental staircase, the North Gate, and a ramp were added to the acropolis and the walls were extended to include the Perseia spring within the fortifications. The spring was named after the city’s mythological founder and was reached by an impressive corbelled tunnel (or syrinx) with 86 steps leading down 18m to the water source. It is argued by some scholars that these architectural additions are evidence for a preoccupation with security and possible invasion. This second palace was also destroyed, this time with signs of fire. Some rebuilding did occur and pottery finds suggest a degree of prosperity returned briefly before another fire ended the occupation of the site until a brief revival in Hellenistic times. With the decline of Mycenae, Argos became the dominant power in the region. Reasons for the demise of Mycenae and the Mycenaean civilization are much debated with suggestions including natural disasters, over-population, internal social and political unrest or invasion from foreign tribes.

Cancellation Policy

All cancellations must be confirmed by Olive Sea Travel.

Regarding the Multiple Day Tours:

Cancellations up to 30 Days before your service date are 100% refundable.

Cancellation Policy:

- Licensed Tour Guides and Hotels are external co-operators & they have their own cancellation policy.

- Apart from the above cancellation limits, NO refunds will be made. If though, you fail to make your appointment for reasons that are out of your hands, that would be, in connection with the operation of your airline or cruise ship or strikes, extreme weather conditions or mechanical failure, you will be refunded 100% of the paid amount.

- If your cancellation date is over TWO (2) months away from your reservation date, It has been known for third-party providers such as credit card companies, PayPal, etc. to charge a levy fee usually somewhere between 2-4%.

- Olive Sea Travel reserves the right to cancel your booking at any time, when reasons beyond our control arise, such as strikes, prevailing weather conditions, mechanical failures, etc. occur. In this unfortunate case, you shall be immediately notified via the email address you used when making your reservation and your payment WILL be refunded 100%.

Recommended for you

Athens Full Day Private Tour