5 Days

Private Tour

English

UP TO 12 GUESTS

5 Days Private Ancient Cities Tour of Greece from Athens

Got a Question?

Contact UsHighlights

Ancient cities of Greece private tour

Day 1st:

• Corinth Canal

• Ancient Olympia – Archaeological Museum Olympia

Overnight: Olympia

Day 2nd:

• Archaeological Site Mystras

• Village of Mystras

• Ancient Sparta – Archaeological Sparta Museum – Museum of Olive

Overnight: Sparta

Day 3rd:

• Monemvasia

Overnight: Monemvasia

Day 4th:

• Ancient Nemea – Nemea Stadium

• Mycenae – Tiryns

• The picturesque town of Nafplio

• Palamidi – Bourtzi

Overnight: Nafplio

Day 5th:

• Epidaurus

• Ancient Corinth – Temple of Apollo

Itinerary

1st Day:

The tour starts with a drive along the coast. On the way you will view some Greek seaside villages and the island of Salamis (where the historical naval battle took place between the Athenians and the Persians). Our first stop the Corinth Canal. Opened in 1892 separating the Peloponnese peninsula from the rest of Greece and connecting the Saronic Gulf to the Corinthian Sea. You will have time to walk across on a pedestrian bridge to admire the canal closer, (if you’re game) on some days bungee jumping is an option.

After this small stop, we will drive to Ancient Olympia following the main highway constructed within the mountains of Peloponnese and as we continue we will reach rural roads between small  Greek villages to finally find the western coast facing the Ionian Sea. After a scenic route, we will reach the small village of Ancient Olympia, going passed the river Alfeios, located exactly at the sacred land that gave birth to the Olympic Games, the village is offered for a relaxing walk and of course a traditional Greek meal. After settling at the hotel we will head towards visiting the site and the museum of Ancient Olympia.

Greek villages to finally find the western coast facing the Ionian Sea. After a scenic route, we will reach the small village of Ancient Olympia, going passed the river Alfeios, located exactly at the sacred land that gave birth to the Olympic Games, the village is offered for a relaxing walk and of course a traditional Greek meal. After settling at the hotel we will head towards visiting the site and the museum of Ancient Olympia.

You will have the privilege of coming across one of the largest sites in Greece, the birthplace of the Olympic Games the Sanctuary of Olympian Zeus. Walking in the site you will pass by the Gymnasium, the Palaestra, the workshop of Phidias, the Temple of Zeus and you will end up at the Stadium where every four years the Greeks competed for glory and spiritual elevation honoring their cities. The museum is also unique as it includes the renowned statue “Hermes of Praxiteles” with its perfect analogies and tools that belonged to Phidias himself. With these tools, he managed to create one of the seven wonders of the world “the gold ivory statue of Zeus”. Then you can rest in your hotel.

2nd Day:

Having spent the night at Olympia the next morning we will drive to the village of Mystras again following the Ionian coastline heading south. On reaching Mystras you will automatically understand why this location stands so unique within the Greek sites.

Known as the ghost city, fortified on a citadel, Mystras is one of the two locations in Greece that preserves not only medieval churches but also ordinary houses, mansions and palaces of the Byzantine Empire in combination with Frankish elements.

Walking in the site on the higher ground you will reach the citadel and enjoy a magnificent view of the surrounding areas while walking downhill you will meet the palaces and the Royal courtyards. Although known as the ghost city most of the monasteries are still in use and the monks will gladly show you around their small society. Before you exit you will come across the chapel of St. Demetrios, on its floor survives a plaque depicting a two head eagle (the symbol of Byzantium). It was on this very plaque that Konstantine Palaiologos kneeled before he was crowned the last emperor of the Byzantium.

Before visiting Sparta we will stop at a traditional Greek tavern at the small village of Mystras.

Following that, we will spend the rest of our time in Sparta known as the eternal rival city of the Athenian Democracy. Sparta revolved around a different Cosmotheory for the ancient Greek standards. Initially known as the birth place of Helen of Troy and the Kingdom of Menelaus (in the Mycenaean period), Sparta was organized as a purely military society in the ancient Greek period. It was the city of the two Kings were a few aristocrats ruled and of course the city where Leonidas and his 300 Spartans marched from to face the Persian army in Thermopylae in 480 BCE. The city whose one soldier counted as ten soldiers from any other Greek city.

Reaching Sparta we will visit the ancient citadel where you will have a view of the ancient theater being revealed gradually in front of your eyes. Continuing we will pass in front of the stadium where the statue of King Leonidas stands marking the ending point of Spartathlon race (Athens – Sparta 245,3 km). Then you can rest in your hotel.

3rd Day:

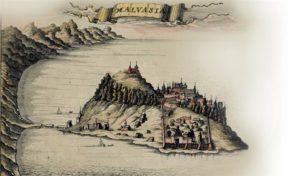

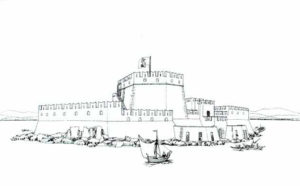

After spending the night at Sparta we will drive to Monemvasia, a unique city of Greece’s medieval history unlike Mystras, Monemvasia is a living old city, developed on an island that is connected to the Greek mainland. A fortress and a prosperous city of the Byzantine empire Monemvasia (literally means one entrance) still survives, the narrow streets, the mansions, the small houses, the churches, the wall, the gate and the citadel, the city is still inhabited. Here history truly comes alive, we will spend the rest of the day at Monemvasia where you can have lunch by the sea upon the old wall and walk in the city discovering points of interest.

4th Day:

The tour continues on the 4th day with our morning, driving towards Nemea. Nemea is mainly known for the Nemean Games the ancient Greek stadium and the temple of Zeus but also for the vineyards. Nemea has the most wineries in Greece as grape growing has been a tradition here since ancient times. In the site apart from the museum and the sanctuary, the stadium makes the difference. One of the best-preserved stadiums, located on a higher level still preserves the tunnel through which the athletes entered the stadium.

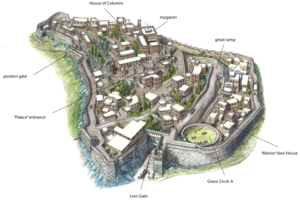

Then we will drive to Mycenae, The site is located just a few kilometers out of the modern village of Mycenae and there you will be able to see the findings that date back to the 2nd millennium B.C.E. representing the era of Achilles Agamemnon and Helen of Troy. In the site you will see, the renowned Lions Gate (the oldest architectural sculpture in Europe), the cyclopean walls, the burial circle A and the remains of Agamemnon’s Palace. Within the site, there is a modern museum exhibiting the findings of the “City of Gold” before leaving the site we will make a small stop at the treasury of Atreus, the best-preserved Tholos tomb, one of the finest examples of the Mycenaean architecture.

burial circle A and the remains of Agamemnon’s Palace. Within the site, there is a modern museum exhibiting the findings of the “City of Gold” before leaving the site we will make a small stop at the treasury of Atreus, the best-preserved Tholos tomb, one of the finest examples of the Mycenaean architecture.

Following we will visit a second Mycenaean site, Tiryns standing very close to Mycenae, a fortress of the same period not that well preserved but preserving unique parts of the fortification like the tunnels created in the wall. According to Greek mythology, Hercules visited Tiryns to be given his 12 labors by his cousin Eyrystheas, King of Tiryns.

Just a few minutes away from Tiryns is the city of Nafplio where we will spend the rest of the day that will bring us to a more recent part of Greek history. Considered as the most scenic city, it functioned as the capital of Greece until 1834. It offers you an outstanding combination of fortresses and castle (Palamidi), Bourtzi, a huge port opened to the Aegean Sea and the unique architecture of the old city of Nafplion revealing Venetian, neoclassical and oriental elements. After walking in the idyllic old city we will stop for lunch at a traditional tavern by the sea and we will drive up until the castle of Palamidi to visit the best-preserved castle in the Peloponnese peninsula. A combination of tunnels, staircases, and bridges still preserves the original shape that had in 1711 at the same time standing above the city it offers you a breathtaking view of the other two fortresses (Acronafplia and Bourtzi) that once protected the city through land and sea. The next stop will be the hotel and after you rest you will have free time to discover more things in this historical city.

5th Day:

For our last day, we will depart from Nafplio towards Epidaurus but before we leave we will drive up until the castle of Acronafplia to have a unique view of the city and the gulf opened in front of it  as your last memory of Nafplion for this trip.

as your last memory of Nafplion for this trip.

After leaving, in a short drive, you will be able to visit one of the most important ancient Greek sanctuaries dedicated to god Asclepius the god of healing and medicine located in a peaceful environment spread on a hilly area reaching its highest point which is the theater of Epidaurus. The best-preserved ancient Greek theater dated 4th century B.C.E. proof of what miracles the ancient Greek minds could create. You can test the acoustic great, even today and climb up until the upper seats just to close your eyes and dream you attended an ancient Greek tragedy. After having seen the sacred land of god Asclepius we will head towards Ancient Corinth.

The last stop before we return will be Ancient Corinth located in the province of Corinthia, just by the Corinth Canal. The city dominated by the hill of Acrocorinth and the old Castle, the oldest and largest castle in southern Greece. The site located at the foot of the hill includes the Roman Agora of Corinth, the temple of God Apollo and a small museum. Apart from its archaeological and historical interest Ancient Corinth is also one of the most popular religious destinations in Greece as this was where the Apostle Paul preached Christianity, was judged by the tribunal in the Agora and established the best organized Christian church of that period.

After the site, we will have a traditional Greek lunch with a sea view and will then make our way back to Athens.

Inclusions - Exclusions

Private Tours are personal and flexible just for you and your party.

Inclusions:

- Professional Drivers with Deep knowledge of history. [Not licensed to accompany you in any site.]

- Accommodation with breakfast (According to your booking)

- Hotel pickup and drop-off

- Guaranteed to skip the long lines / Tickets are NOT included.

- Fuel surcharge

- Local taxes

- Bottled water

Exclusions:

- Entrance Fees

- Licensed Tour guide on request (Additional cost )

- Accommodation with breakfast (According to your booking)

- Personal expenses (drinks, meals, etc.)

- Airport Pick Up and drop-off (Additional cost)

Entrance Fees

ADMISSION FEES FOR SITES:

Summer Period: 151€ per person

(1 April – 31 October)

Ancient Olympia: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Mystras: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Ancient Sparta: 10€ (10:00- 18:00, Tuesdays closed)

Museum Olive and Olive Oil: 6€ (10:00- 18:00, Tuesdays closed)

Ancient Nemea: 10€ (08:00- 17:00)

Mycenae: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Palamidi Castle: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Tiryns: 10€ (08:30- 15:30)

Epidaurus: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Ancient Corinth: 15€ (08:00- 20:00)

Winter Period: 151€ per person

(1 November – 31 March)

Ancient Olympia: 20€ (08:00- 15:00)

Mystras: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Ancient Sparta: 10€ (10:00- 15:00, Tuesdays closed)

Museum Olive and Olive Oil: 6€ (10:00- 17:00, Tuesdays closed)

Ancient Nemea: 10€ (08:00- 15:30, Tuesday closed)

Mycenae: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Palamidi Castle: 20€ (08:30- 15:30)

Tiryns: 10€ (08:30- 15:30)

Epidaurus: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Ancient Corinth: 15€ (08:00- 15:30)

Free admission days:

- 6 March (in memory of Melina Mercouri)

- 18 April (International Monuments Day)

- 18 May (International Museums Day)

- The last weekend of September annually (European Heritage Days)

- Every first and third Sunday from November 1st to March 31st

- 28 October

Holidays:

- 1 January: closed

- 25 March: closed

- 1 May: closed

- Easter Sunday: closed

- 25 December: closed

- 26 December: closed

Free admission for:

- Children & young people up to the age of 25 from EU Member- States

- Children & young people from up to the age of 18 from Non- European Union countries

- Persons over 25 years, being in secondary education & vocational schools from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers during the visits of schools & institutions of Primary, Secondary & Tertiary education from EU Member- States

- People entitled to Social Solidarity income & members depending on them

- Persons with disabilities & one escort (only in the case of 67% disability)

- Refugees

- Official guests of the Greek State

- Members of ICOM & ICOMOS

- Members of societies & Associations of friends of State Museums & Archaeological sites

- Scientists licensed for photographing, studying, designing or publishing antiquities

- Journalists

- Holders of a 3- year Free Entry Pass

Reduced admission for:

- Senior citizens over 65 from Greece or other EU member-states, during

the period from 1st of October to 31st of May - Parents accompanying primary education schools visits from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers of educational visits of schools & institutions of primary, secondary & tertiary education from non European Union countries

Reduced & free entrance only upon presentation of the required documents

History

Corinth Canal:

The famous Corinth Canal connects the Gulf of Corinth with the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea. It cuts through the narrow Isthmus of Corinth and separates the Peloponnesian peninsula from the Greek mainland, thus effectively making the former an island. The canal is 6.4 kilometers in length and only 21.3 meters wide at its base. Earth cliffs flanking either side of the canal reach a maximum height of 63 meters. Aside from a few modest-sized cruise ships, the Corinth Canal is unserviceable to most modern ships. The Corinth Canal, though only completed in the late 19th century, was an idea and dream that dates back over 2000 thousand years.

Before it was built, ships sailing between the Aegean and Adriatic had to circumnavigate the Peloponnese adding about 185 nautical miles to their journey. The first to decide to dig the Corinth Canal was Periander, the tyrant of Corinth (602 BCE). Such a giant project was above the technical capabilities of ancient times so Periander carried out another great project, the diolkós, a stone road, on which the ships were transferred on wheeled platforms from one sea to the other. Dimitrios Poliorkitis, king of Macedon (c. 300 BCE), was the second who tried, but his engineers insisted that if the seas where connected, the more northerly Adriatic, mistakenly thought to be higher, would flood the more southern Aegean. At the time, it was also thought that Poseidon, the god of the sea, opposed joining the Aegean and the Adriatic. The same fear also stopped Julius Caesar and Emperors Hadrian and Caligula. The most serious try was that of Emperor Nero (67 CE). He had 6,000 slaves for the job. He started the work himself, digging with a golden hoe, while music was played. However, he was killed before the work could be completed.

In the modern era, the first who thought seriously to carry out the project was Kapodistrias (c. 1830), the first governor of Greece after the liberation from the Ottoman Turks. But the budget, estimated at 40 million French francs, was too much for the Greek state. Finally, in 1869, the Parliament authorized the Government to grant a private company (Austrian General Etiene Tyrr) the privilege to construct the Canal of Corinth. Work began on Mar 29, 1882, but Tyrr’s capital of 30 million francs proved to be insufficient. The work was restarted in 1890, by a new Greek company (Andreas Syggros), with a capital of 5 million francs. The job was finally completed and regular use of the Canal started on Oct 28, 1893. Due to the canal’s narrowness, navigational problems and periodic closures to repair landslips from its steep walls, it failed to attract the level of traffic anticipated by its operators. It is now used mainly for tourist traffic. The bridge above is perfect for bungee jumping.

Ancient Olympia:

The history of Olympia is strongly connected to the Olympic Games. Historical records indicate that the games began in 776 BCE as a local festival to honor god Zeus. However, along the centuries, these games gained more and more popularity and all city-states of Greece would send their finest men to participate in the games. This event was so important for the ancient world that even all warfare would stop for a month so that the towns would send their best youths to participate in the games. This athletic festival occurred every four years and lasted for five days, including wrestling, chariot and horse racing, the pentathlon (discus throwing, javelin throwing, long jump, running and pancratium).

However, the athletes would stay for 1 or 2 months before the games in Olympia to train in the Palaestra. Before the games, the high priestess of Olympia marked the beginning of the games lighting the Olympic flame. Also, offerings and ceremonies in the temple of Zeus and the temple of Hera were practiced to ask for the favor of the gods. The games would take place in the stadium and people would watch them from the hills around it. All athletes were male and would take part in the games in total nudity. Women were forbidden under the penalty of death to part take in the games or even watch them as a spectator. The only woman who could watch the games, and in fact from a privileged spot, was the priestess of the temple of Demeter in Olympia.

However, the athletes would stay for 1 or 2 months before the games in Olympia to train in the Palaestra. Before the games, the high priestess of Olympia marked the beginning of the games lighting the Olympic flame. Also, offerings and ceremonies in the temple of Zeus and the temple of Hera were practiced to ask for the favor of the gods. The games would take place in the stadium and people would watch them from the hills around it. All athletes were male and would take part in the games in total nudity. Women were forbidden under the penalty of death to part take in the games or even watch them as a spectator. The only woman who could watch the games, and in fact from a privileged spot, was the priestess of the temple of Demeter in Olympia.

There were no seats for the spectators and all people regardless of their social state would sit on the ground. The Hellanodikae, a body of priests, were responsible for naming the winners. The reward of the winning athletes was a crown from a wild olive tree, which was enough to honor him, his family and his city for decades. In fact, it was such an honor to be an Olympic winner that, their town even pulled down a part of their city walls, as the town would be protected by the winner. At the same time, the political personalities from different parts of Greece took advantage of the games to make speeches and try to resolve differences against each other. The games were also a good opportunity for traders to make business deals. Unfortunately, in 393 AD, the Olympic Games were suspended by the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius, as it was considered a pagan custom. It was the time when Christianity was the dominant religion of the Byzantine Empire and everything connected to the ancient Greek spirit was considered pagan. Thus the games were stopped, the temples of Olympia were turned into churches and important statues, among which the golden statue of Zeus, a miracle of the ancient world, was transferred to Constantinople.

The revival of the Olympic Games in the modern era was an idea of the French Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894 and only two years later, in 1896, the first modern Olympic Games took place in Athens, at the renovated Panathenaic Stadium. Since then, the games take place every 4 years in a different place in the world every time.

Sparta:

Sparta was a warrior society in ancient Greece that reached the height of its power after defeating rival city-state Athens in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). Spartan culture was centered on loyalty to the state and military service. At age 7, Spartan boys entered a rigorous state-sponsored education, military training, and socialization program. Known as the Agoge, the system emphasized duty, discipline, and endurance. Although Spartan women were not active in the military, they were educated and enjoyed more status and freedom than other Greek women. Because Spartan men were professional soldiers, all manual labor was done by a slave class, the Helots. Despite their military power, the Spartan’s dominance was short-lived: In 371 BCE, they were defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Lefktra, and their empire went into a long period of decline.

SPARTAN SOCIETY:

Sparta, also known as Lacedaemon, was an ancient Greek city-state located primarily in the present-day region of southern Greece called Laconia. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans, or Spartiates, who were full citizens the Helots, or serfs/slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens. The Perioeci, whose name means “dwellers-around,” worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans.

Did You Know?

The word “spartan” means self-restrained, simple, frugal and austere. The word “laconic”, meaning pithy and concise, is derived from the Spartans, who prized brevity of speech.

All healthy male Spartan citizens participated in the compulsory state-sponsored education system, the Agoge, which emphasized obedience, endurance, courage, and self-control. Spartan men devoted their lives to military service and lived communally well into adulthood. A Spartan was taught that loyalty to the state came before everything else, including one’s family.

The Helots, whose name means “captives,” were fellow Greeks, originally from Laconia and Messenia, who had been conquered by the Spartans and turned into slaves. The Spartan’s way of life would not have been possible without the Helots, who handled all the day-to-day tasks and unskilled labor required to keep society functioning: They were farmers, domestic servants, nurses and military attendants.

Spartans, who were outnumbered by the Helots, often treated them brutally and oppressively in an effort to prevent uprisings. Spartans would humiliate the Helots by doing such things as forcing them to get drunk on wine and then watch them make fools of themselves in public. (This practice was also intended to demonstrate to young people how an adult Spartan should never act, as self-control was a prized trait.) Methods of mistreatment could be far more extreme: Spartans were allowed to kill Helots for being too smart or too fit, among other reasons.

Spartans, who were outnumbered by the Helots, often treated them brutally and oppressively in an effort to prevent uprisings. Spartans would humiliate the Helots by doing such things as forcing them to get drunk on wine and then watch them make fools of themselves in public. (This practice was also intended to demonstrate to young people how an adult Spartan should never act, as self-control was a prized trait.) Methods of mistreatment could be far more extreme: Spartans were allowed to kill Helots for being too smart or too fit, among other reasons.

THE SPARTAN MILITARY:

Unlike Greek city-states such as Athens, a center for the arts, learning, and philosophy, Sparta was centered on a warrior culture. Male Spartan citizens were allowed only one occupation: solider. Indoctrination into this lifestyle began early. Spartan boys started their military training at age 7, when they left home and entered the Agoge. The boys lived communally under austere conditions. They were subjected to continual physical, competitions (which could involve violence), given meager rations and expected to become skilled at stealing food, among other survival skills.

The teenage boys who demonstrated the most leadership potential were selected for participation in the Crypteia, which acted as a secret police force whose primary goal was to terrorize the general Helot population and murder those who were troublemakers. At age 20, Spartan males became full-time soldiers and remained on active duty until age 60.

The Spartans’ constant military drilling and discipline made them skilled at the ancient Greek style of fighting in a phalanx formation. In the phalanx, the army worked as a unit in a close, deep formation, and made coordinated mass maneuvers. No one soldier was considered superior to another. Going into battle, a Spartan soldier, or hoplite, wore a large bronze helmet, breastplate and ankle guards, and carried a round shield made of bronze and wood, a long spear and sword. Spartan warriors were also known for their long hair and red cloaks.

SPARTAN WOMEN AND MARRIAGE:

Spartan women had a reputation for being independent-minded and enjoyed more freedom and power than their counterparts throughout ancient Greece. While they played no role in the military, female Spartans often received a formal education, although separate from boys and not at boarding schools. In part to attract mates, females engaged in athletic competitions, including javelin-throwing and wrestling, and also sang and danced competitively. As adults, Spartan women were allowed to own and manage the property. Additionally, they were typically unencumbered by domestic responsibilities such as cooking, cleaning and making clothing, tasks which were handled by the helots.

Marriage was important to Spartans, as the state put pressure on people to have male children who would grow up to become citizen-warriors and replace those who died in battle. Men who delayed marriage were publically shamed, while those who fathered multiple sons could be rewarded.

In preparation for marriage, Spartan women had their heads shaved; they kept their hair short after they wed. Married couples typically lived apart, as men under the age of 30 were required to continue residing in communal barracks. In order to see their wives during this time, husbands had to sneak away at night.

DECLINE OF THE SPARTANS:

In 371 BCE, Sparta suffered a catastrophic defeat at the hands of the Thebans at the Battle of Lefktra. In a further blow, late the following year, the Theban general Epaminondas (418 – 362 BCE) led an invasion into the Spartan territory and oversaw the liberation of the Messenian Helots, who had been enslaved by the Spartans for several centuries. The Spartans would continue to exist, although as a second-rate power in a long period of decline. In 1834, Otto (1815 – 67), the king of Greece, ordered the founding of the modern-day town of Spartion at the site of ancient Sparta.

Mystras:

The town of Mystras was founded in the 13th century, after the conquest of Constantinople by the Crusades. The Franks dominated Morea, the area is known today as the Peloponnese and Prince William II Villehardouin built a fortress on the top of the mountain Mystras (alias Mytzithras). In 1259, Villehardouin was captured on the battlefield of Pelagonia by Michael VIII Paleologos, a Byzantine emperor, that set him free in exchange for the castles of Monemvasia and Mystras. The town thus becomes a Byzantine area and gets influenced by the Byzantine architecture and artwork. Since then, Mystras became an important military center and the inhabitants of the neighboring areas started building their homes on the slope of Mystras, seeking security. Although the original area was protected by walls, the increasing number of houses made it necessary to build more walls to enclose new clusters of houses. This fact explains the walls that Mystras hosts till this very day, which constitute a great attraction for visitors. The first wall was called Chora and the second one Kato Chora. The cathedral of Sparta was also re-established in Mystras. As a result,  these movements gave importance to the city that became the capital of Moreas between the mid-14th and mid-15th centuries. Mystras had a permanent lord that ruled for indefinite terms and had the title of Despot. Along time, Mystras became the capital of the famous Despotate of Moreas. From this point on, its history continues with plenty of fights against foreign invaders, including Franks, Slavs, Turks, and Albanians.

these movements gave importance to the city that became the capital of Moreas between the mid-14th and mid-15th centuries. Mystras had a permanent lord that ruled for indefinite terms and had the title of Despot. Along time, Mystras became the capital of the famous Despotate of Moreas. From this point on, its history continues with plenty of fights against foreign invaders, including Franks, Slavs, Turks, and Albanians.

The first Despot of Mystras was Emmanuel Kantakouzenos, who ruled from 1348 to 1380. Matthew Kantakouzenos (1380-1383) and Demetrios Kantankouzenos (1383-1384) were the following Despots. Then, Theodor I Paleologos ruled until 1407. During this period, the prosperity of Mystras reached a high level. In fact, the Neoplatonist philosopher George Gemistos Plethon (1355-1452) founded a philosophic school there in 1400. Theodore II ruled from 1407 to 1443. His younger brother, Constantinos Paleologos, ruled Mystras from 1443 to 1449 and then became the last emperor of the Byzantine Empire. After the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, his younger brother Demetrius surrendered the castle to them in 1460.

Under Turkish occupation, Mystras gradually started to decline. In 1687, the Venetians conquered the area but the Turks gained it back. The inhabitants made many courageous efforts to free their city from the Turks but with no result. In 1825, the Albanian Turks slaughtered the population and destroyed the area, which was later abandoned. Finally, it was set free a few years later and formed part of the first Greek state.

In 1831, King Otto founded the new city of Sparta (9 km away) and this resulted in the final decline and abandonment of Mystras. Most families moved to Sparta and others to New Mystras, a small village built in the countryside. In 1952, the remaining properties were expropriated and the city started to be appreciated as one of the most interesting Greek archaeological sites. In 1989, the old town of Mystras was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Monemvasia:

The history of the town of Monemvasia starts with its name, as the words, it derives from moni and emvasis, which means a single passage. The name comes from the Venetians who saw that the only passage to the Castle Town of Monemvasia was through a paved walkway that they built. Before this walkway was constructed, the only way to go to the town was by boat. The Castle Town of Monemvasia was constructed in the Medieval Times. From that moment on, the rich history of Monemvasia has been full of prosperity and glory, as well as declination and invasions. From the 10th century, it started to develop in economic terms, becoming an important trade and maritime center. Then, the city bravely resisted the Norman and Arab invasions in the mid-12th century. However, this was followed by another invasion effort by William Villehardouin. Unfortunately, this time the town was defeated in 1249, due to hunger caused by the three-year siege. Ten years after this, Michael Paleologus imprisoned Villehardouin, who reclaimed his freedom by taking the side of the Byzantines, helping them to regain the fortresses of Monemvasia, Mystras, and Mani. The Byzantine benefited from the development of Monemvasia in the economic, cultural, and military fields. However, this gradual progress attracted the pirates causing the famous raid by the Catalans in 1292. The efforts of keeping the pirates away brought inhabitants in touch with naval resources in terms of warfare. In 1419, the Venetian invasions caused the decline of the Byzantine Empire. In 1460, Mystras was ruled by the Ottomans, leaving Monemvasia as the only city that kept its autonomy. In the middle 15th century, the Venetians recaptured Monemvasia as it was considered a strategic point in the Aegean Sea. Eventually, Monemvasia was sold to the Ottomans in 1715. Around 1770, when the Russian-Turkish War occurred, it started to fall apart economically. Monemvasia was finally liberated on July 23rd, 1821 and became part of the first free Greek State.

However, this was followed by another invasion effort by William Villehardouin. Unfortunately, this time the town was defeated in 1249, due to hunger caused by the three-year siege. Ten years after this, Michael Paleologus imprisoned Villehardouin, who reclaimed his freedom by taking the side of the Byzantines, helping them to regain the fortresses of Monemvasia, Mystras, and Mani. The Byzantine benefited from the development of Monemvasia in the economic, cultural, and military fields. However, this gradual progress attracted the pirates causing the famous raid by the Catalans in 1292. The efforts of keeping the pirates away brought inhabitants in touch with naval resources in terms of warfare. In 1419, the Venetian invasions caused the decline of the Byzantine Empire. In 1460, Mystras was ruled by the Ottomans, leaving Monemvasia as the only city that kept its autonomy. In the middle 15th century, the Venetians recaptured Monemvasia as it was considered a strategic point in the Aegean Sea. Eventually, Monemvasia was sold to the Ottomans in 1715. Around 1770, when the Russian-Turkish War occurred, it started to fall apart economically. Monemvasia was finally liberated on July 23rd, 1821 and became part of the first free Greek State.

Nemea and Nemean Games:

SETTLEMENT

Lying in foothills of the Arcadian mountains, 333m above sea level in a long narrow valley is Nemea. The name Nemea comes from the Greek word meaning to graze. Inhabited since Early  Neolithic times (6000 to 5000 BCE) it was settled throughout the Bronze Age shown by rock-cut tombs, dating from the mid-16th century BCE to the 12th century BCE. The site reached its peak from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE then, every two years, athletes and spectators gathered for the Pan-Hellenic Games. Following the movement of the Games to Argos, the site was largely abandoned and used merely for agricultural purposes. In the 4th century, an early Christian settlement was established with a Basilica and baptistery. This settlement was abandoned in the mid-6th century when the valley’s river dried up.

Neolithic times (6000 to 5000 BCE) it was settled throughout the Bronze Age shown by rock-cut tombs, dating from the mid-16th century BCE to the 12th century BCE. The site reached its peak from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE then, every two years, athletes and spectators gathered for the Pan-Hellenic Games. Following the movement of the Games to Argos, the site was largely abandoned and used merely for agricultural purposes. In the 4th century, an early Christian settlement was established with a Basilica and baptistery. This settlement was abandoned in the mid-6th century when the valley’s river dried up.

Origins of the Games

The mythical origin of the Games is sometimes credited to Hercules. After his first labor, where he had to kill the Nemean lion, he established athletic games in honor of his father Zeus. A second and more likely mythological origin is the story of Opheltes. Lykourgos, the priest-king had a son Opheltes and seeking to protect his son, Lykourgos asked the Delphic oracle for advice. The response of the oracle was to prevent the baby from touching the ground until he had learned to walk. Opheltes was put under the care of a slave called Hypsipyle but while engaged fetching water for some passing champions on their way to Thebes (the famous Seven against Thebes) the unattended baby was fatally attacked by a snake while he slept in a bed of wild celery. Taking this as a bad omen, the champions organized funeral games to appease the gods and pay tribute to the unfortunate Opheltes.

The Events

The events of the Nemean Games were held shortly after the summer solstice. Athletes came from all over Greece and even beyond to compete and were separated into three age groups: boys (12-16 years), youths (16-20) and men (over 21). They were supervised by specially trained Hellanodikai who acted as both referees and as judges and wore black. Athletes competed naked and victors were awarded a crown of wild celery. The most important event was the stadion or foot-race over one length of the stadium track. Other events were foot-races over various stadium lengths: the diaulos (double), the hippios (four lengths), dolichos (as many as twenty-four lengths) and the hoplitodromos (as the dialogs but run in hoplite armor). In addition, there were competitions in boxing (pyx), wrestling (pale), combined boxing and wrestling (pankration) and the pentathlon – stadion race, wrestling, javelin (akonti), discus (diskos) and long jump (halma). Horse races were also held on the hippodrome track and included the four-horse chariot race of 8,400 m (tethrippon), the two-horse chariot race of 5,600 m (synoris) and the horse race of 4,200 m (keles). Two further competitions were for heralds (kerykes) and trumpeters (salpinktai). The winner of the first won the right to announce the sporting events and victors and the latter won the privilege of announcing the herald. In the Hellenistic period competitions in singing, flute and lyre playing were also added.

ARCHITECTURAL REMAINS

In 1884 a French archaeologist made surface excavations. Excavations were also carried out between 1924-6 by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and again in 1964. Then more systematically from 1973 by the University of California at Berkeley, which continues to the present day.

Remains at the site are dominated by the impressive Temple of Zeus constructed (330 BCE). This was built on the site of an earlier temple (6th century BCE). The new temple was built of local limestone and covered in fine marble-dust stucco with the inner sima in marble. The entrance had a large ramp rather than steps and inside was a large statue of Zeus. The temple measured approximately 22 x 42 m. The Doric exterior (peristyle) had 6 x 12 unusually slender columns, 10.33 m high. The Corinthian inner columns (6 x 4) also supported a secondary story of Ionic columns. There was no exterior decoration. The wooden and terracotta tiled roof of the temple collapsed in the 2nd century CE and in the 5th century CE the majority of columns collapsed, due to the removal of blocks from the stylobate. Several columns have been re-erected in modern times mostly using the original drums which still lie scattered around the site.

Alongside the Temple of Zeus was an unusually long (41 m) altar but only its foundations survive. Also near the temple, there is a row of nine small rectangular buildings (oikoi) built in the early 5th century BCE. In the 4th century BCE, the Macedonians added other buildings. These include a Bathhouse, the large Xenon building, a shrine to Opheltes and a triple stone reservoir. The Bathhouse has a large central pool flanked by two tub rooms, each with four stone wash basins. The Xenon was a large rectangular building (85 x 20 m) with fourteen rooms and originally two stories but only the foundations remain (probably used as accommodation for athletes and trainers). The shrine to Opheltes was built on a small man-made mound and covered an area of 850 square meters enclosed by a low stone wall. Inside were two altars, a cenotaph to commemorate Opheltes and at least some trees, planted to form a sacred grove in a corner. The shrine was a renovation of the earlier 6th-century one. The triple reservoirs measure 3 x 9.8 m and reach a depth of 8 m; their exact function is not known.

Linked by a road to the sacred complex, the stadium of Nemea which is visible today dates from 330-320 BCE and was built between two natural ridges providing an elevated vantage point for spectators and allowing a capacity as high as 30,000 people. A locker-room (apodyterion), once with an open central court, is connected to the stadium track by an arched tunnel measuring over 36 m in length and nearly 2.5 m in height. The track itself is the usual 600 ancient feet in length (178 m) with small marker posts indicating every 100ft. Still in situ is the stone starting line (balbis) where athletes placed their front foot.

Important archaeological finds at the site include a rare double-tray sacrificial table and a range of bronze sporting equipment including javelin tips, strigils, and a discus. Other finds include votive statues, jumping stones and an impressive array of coins and pottery which attest to the wide geographical appeal of the Nemean Games. Since 1996 and held every four years, there has been a revival of the ancient Nemean Games with footraces held in the ancient stadium.

Mycenae:

Mycenae was a fortified late Bronze Age city located between two hills on the Argolis plain of the Peloponnese, Greece. The acropolis today dates from between the 14th and 13th century BCE when the Mycenaean civilization was at its peak of power, influence and artistic expression.

IN MYTHOLOGY:

IN MYTHOLOGY:

In Greek mythology, the city was founded by Perseus, who gave the site its name either after his sword’s scabbard (mykes) fell to the ground and was regarded as a good omen or as he found a water spring near a mushroom (mykes). Perseus was the first king of the Perseid dynasty which ended with Eurytheus (instigator of Hercules’ famous twelve labours). The succeeding dynasty was the Atreids, whose first king, Atreus, is traditionally believed to have reigned around 1250 BCE. Atreus’ son Agamemnon is believed to have been not only king of Mycenae but of all of the Achaean Greeks and the leader of their expedition to Troy to recapture Helen. In Homer’s account of the Trojan War in the Iliad, Mycenae (or Mykene) is described as a ‘well-founded citadel’, as ‘wide-wayed’ and as ‘golden Mycenae’, the latter supported by the recovery of over 15 kilograms of gold objects recovered from the shaft graves in the acropolis.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW:

Situated on a rocky hill (40-50 m high) commanding the surrounding plain as far as the sea 15 km away, the site of Mycenae covered 30,000 square meters and has always been known throughout history. First excavations were begun by the Archaeological Society of Athens in 1841 and then continued by the famous Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 that discovered the magnificent treasures of Grave Circle A. The archaeological excavations have shown that the city has a much older history than traditional Greek literature described.

Even though the site was inhabited since Neolithic times, it is not until 2100 BCE that the first walls, pottery finds (including imports from the Cycladic islands) and pit and shaft graves with higher quality grave goods appear. These, collectively, suggest greater importance and prosperity in the settlement.

Since 1600 BCE there is evidence of an elite presence on the acropolis: high-quality pottery, wall paintings, shaft graves and an increase in the surrounding settlement with the construction of large tholos tombs. From the 14th century BCE the first large-scale palace complex is built (on three artificial terraces), so is the celebrated tholos tomb, the Treasury of Atreus, a monumental circular building with corbelled roof reaching a height of 13.5 m and 14.6 m in diameter and approached by a long walled and unroofed corridor 36 m long and 6m wide. Fortification walls, of large roughly worked stone blocks, surrounding the acropolis (of which the north wall is still visible today), flood management structures such as dams, roads, Linear B tablets and an increase in pottery imports (fitting well with theories of contemporary Mycenaean expansion in the Aegean) illustrate the culture was at its zenith.

ARCHITECTURE:

The large palace structure built around a central hall or Megaron is typical of Mycenaean palaces. Other features included a secondary hall, many private rooms, and a workshop complex.  Decorated stonework and frescoes and a monumental entrance, the Lion Gate (a 3 m x 3 m square doorway with an 18-ton lintel topped by two 3 m high heraldic lions and a column altar), added to the overall splendor of the complex. The relationship between the palace and the surrounding settlement and between Mycenae and other towns in the Peloponnese is much discussed by scholars. Concrete archaeological evidence is lacking but it seems likely that the palace was a center of political, religious and commercial power. Certainly, high-value grave goods, administrative tablets, pottery imports and the presence of precious materials deposits such as bronze, gold, and ivory would suggest that the palace was, at the very least, the hub of a thriving trade network.

Decorated stonework and frescoes and a monumental entrance, the Lion Gate (a 3 m x 3 m square doorway with an 18-ton lintel topped by two 3 m high heraldic lions and a column altar), added to the overall splendor of the complex. The relationship between the palace and the surrounding settlement and between Mycenae and other towns in the Peloponnese is much discussed by scholars. Concrete archaeological evidence is lacking but it seems likely that the palace was a center of political, religious and commercial power. Certainly, high-value grave goods, administrative tablets, pottery imports and the presence of precious materials deposits such as bronze, gold, and ivory would suggest that the palace was, at the very least, the hub of a thriving trade network.

The first palace was destroyed in the late 13th century, probably by an earthquake and then (rather poorly) repaired. A monumental staircase, the North Gate, and a ramp were added to the acropolis and the walls were extended to include the Perseia spring within the fortifications. The spring was named after the city’s mythological founder and was reached by an impressive corbelled tunnel (or syrinx) with 86 steps leading down 18m to the water source. It is argued by some scholars that these architectural additions are evidence for a preoccupation with security and possible invasion. This second palace was also destroyed, this time with signs of fire. Some rebuilding did occur and pottery finds suggest a degree of prosperity returned briefly before another fire ended the occupation of the site until a brief revival in Hellenistic times. With the decline of Mycenae, Argos became the dominant power in the region. Reasons for the demise of Mycenae and the Mycenaean civilization are much debated with suggestions including natural disasters, over-population, internal social and political unrest or invasion from foreign tribes.

Tiryns:

Tiryns is one of the most important archaeological sites in Argolida, even though it is quite frequently overshadowed by Mycenae and Epidaurus that attract more visitors due to their historical value and their cultural significance. Tiryns, however, will satisfy everyone who wishes to make the trip, since they will not only see the layers of history imprinted on the ruins of a city that flourished for centuries, but also enjoy a breathtaking natural landscape that surrounds it.

Tiryns can be found between Nafplion and Argos, closer to the Argolic plains, which the visitor of the archaeological site can admire from above. The site also overlooks the Argolic gulf with its crystal clear waters. It is not at all difficult to imagine the reasons Tiryns was built and flourished in such a location.

Besides, it is rather possible that Tiryns is even mentioned in the Homeric epics, though it is very difficult to be certain due to the changes in place names. Pausanias, however, who visited it during the 2nd century AD found it already in ruins. The area was always inhabited until the modern years, but it never acquired significance until Heinrich Schliemann revealed its older glory by bringing to light the acropolis and the cyclopean walls.

The archaeologists have discovered evidence that shows that the city was already inhabited in the neolithic period, but it flourished during the Mycenaean era until its days of glory reached an end when Argos, the strongest power in the area, destroyed it. The formerly impressive palace can be found at Lower Acropolis, while at Upper Acropolis you will find the eastern gate.

The hill on which Tiryns is built is surrounded by walls that can be as thick as eight meters, and that’s where they get their name: cyclopean. They are a very difficult structure to build, along with the waterworks of the city.

Just like Mycenae, Tiryns hosts some beehive tombs that are located, as is natural, not in the Acropolis, but a bit farther away.

Tiryns may not be your first choice for a trip to an archaeological site in Argolida. But if you have that itch to get to know the history of a place, then Tiryns can definitely satisfy you.

Nafplio:

The city of Nafplio was the first capital of the modern Greek state. Named after Nafplios, son of Poseidon, and home of Palamidis, their local hero of the Trojan war and supposedly the inventor of weights and measures, lighthouses, the first Greek alphabet and the father of the Sophists. The small city-state made the mistake of allying with Sparta in the second Messenian War (685 – 688 BCE) and was destroyed by Damokratis the king of Argos.

Because of the strength of the fort that sits above the bay, the town of Nafplio became an important strategic and commercial center to the Byzantines from around the sixth century AD. In 1203 Leon Sgouros, ruler of the city, conquered Argos and Corinth, and Larissa to the north, though it failed to successfully conquer Athens after a siege in 1204.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, the Franks, with the help of the Venetians captured the city and nearly destroyed the fortress in the process. In the treaty, the defenders of the city were given the eastern side of the city, called Romeiko and allowed to follow their customs, while the Franks controlled the Akronafplia, which was most of the city at the time. The Franks controlled the city for 200 years and then sold it to the Venetians. The Venetians continued the fortification of the upper town and completed their work in 1470. That same year they built a fort on the small island in the center of the harbor called the Bourtzi. To close the harbor the fort was linked by chains and the town was known as Porto Cadenza, meaning Port of Chains. During this period people flocked to the safety of the fortified city in fear of the Turks and forced the expansion of the city into the lagoon between the sea and the walls of the Akronafplia. The new additions to the city were surrounded with walls and many major buildings were erected including the Church of Saint George. But these new walls didn’t matter because in the treaty with Suleiman the First, Nafplio was handed over to the Turks who controlled the city for 100 years and made it the primary import/export center for mainland Greece.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, the Franks, with the help of the Venetians captured the city and nearly destroyed the fortress in the process. In the treaty, the defenders of the city were given the eastern side of the city, called Romeiko and allowed to follow their customs, while the Franks controlled the Akronafplia, which was most of the city at the time. The Franks controlled the city for 200 years and then sold it to the Venetians. The Venetians continued the fortification of the upper town and completed their work in 1470. That same year they built a fort on the small island in the center of the harbor called the Bourtzi. To close the harbor the fort was linked by chains and the town was known as Porto Cadenza, meaning Port of Chains. During this period people flocked to the safety of the fortified city in fear of the Turks and forced the expansion of the city into the lagoon between the sea and the walls of the Akronafplia. The new additions to the city were surrounded with walls and many major buildings were erected including the Church of Saint George. But these new walls didn’t matter because in the treaty with Suleiman the First, Nafplio was handed over to the Turks who controlled the city for 100 years and made it the primary import/export center for mainland Greece.

In 1686 the Turks surrendered the city to a combined force of Venetians, Germans and Poles, lead by Vice Admiral Morozini and this began the second period of Venetian rule in which massive repairs were made to the fortress and the city including the construction of the fortress in Palamidi. When the Peloponessos falls to the Venetians, Nafplio becomes the capital. But after just thirty years the Turks once again take control of the city, almost totally destroying it, looting it and killing almost all its defenders. Most of the survivors chose to leave and the city while the Turks built mosques, baths and homes in the eastern style which can still be seen.

In April of 1821 Greek chieftains and Philhellenes surrounded the city of Nafplio and liberated it from the Turks under the leadership of Theodore Kolokotronis. Nafplio became the center of activities which would result in the formation of Modern Greece. In 1823 it becomes the capital of the state which is then recognized by the world powers (England, France and Russia) in 1827.

In January of 1828, Ioannis Kapodistrias is recognized as the first governor and arrives in Nafplion. In 1831 King Otto is chosen as the first King of Greece but a month later Kapodistrias is murdered in the Church of Agios Spiridon.

In 1833 King Otto arrives amid great fanfare to the city of Nafplio where he remains until 1834 when the capital of Greece is moved to Athens.

In 1862 there is a rebellion in Nafplio against the monarchy. A siege by the royal army follows. The rebels are given amnesty in 1862. In 1834 Kolokotronis is jailed in the Palamidi fortress. After the capital moves to Athens, the city of Nafplio becomes of less importance. But it still continues to attract visitors to this very day because its history is virtually the history of modern Greece and because every occupying power has left its mark.

The city of Nafplio is like a living museum. It’s also as lively as any city in Greece.

Epidaurus:

Located on the fertile Argolid plain of the east Peloponnese in Greece and blessed with a mild climate and natural springs, the sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus was an important sacred center in both ancient Greek and Roman times.

Epidaurus was named after the hero Epidauros, son of Apollo. Inhabited since Neolithic times, the first significant settlement was in the Mycenaean period. Fortifications, a theatre and tholos tombs have been excavated dating as early as the 15th century BCE, although it was in the 12th century BCE that Epidaurus Limera, with its harbor linking it to the Aegean trade network, particularly flourished.

Epidaurus was named after the hero Epidauros, son of Apollo. Inhabited since Neolithic times, the first significant settlement was in the Mycenaean period. Fortifications, a theatre and tholos tombs have been excavated dating as early as the 15th century BCE, although it was in the 12th century BCE that Epidaurus Limera, with its harbor linking it to the Aegean trade network, particularly flourished.

Earlier regional worship of the deity Maleatas evolved into the later worship of Apollo, who was given similar attributes. However, it was Asclepius (also spelt Asklepios), whom the Epidaurians believed was born on the nearby Mt. Titthion, who took precedence from the 5th century BCE until Roman times in the 4th century CE. Credited with possessing great healing powers (learned from his father Apollo) and also those of prophecy, the god – as manifested in the sanctuary or Asklepieion – was visited from all over Greece by those seeking ease and remedies from their illnesses either by divine intervention or medicines administered by the priests. The sanctuary used the wealth gained from dedications of the worshipers to build an impressive complex of buildings and to sponsor major art projects to beautify the center. Indeed, many of the offerings given were works of art such as statues, pottery vessels, tripods, and even buildings.

At the height of the site’s importance in the 4th century BCE (370 – 250 BCE), major buildings included two monumental entrances (Propylaia); a large temple (380 – 375 BCE) with the typical 6×11 column Doric layout, containing a larger than life-size Chryselephantine statue of a seated Asclepius (by Thrasymedes) and with pediments displaying in statuary the Amazonomachy and the Siege of Troy; temples dedicated to Aphrodite (320 BCE), Artemis and Themis; a sacred fountain; the Thymele (360 – 330 BCE) – around marble building originally with 26 outer Doric columns, a 14 Corinthian columned cella and a mysterious underground labyrinth, perhaps containing snakes which were associated with Asclepius; the columned Abato (or Enkoimeterion) in which patients waited overnight for divine intervention and remedy; other temples, hot and cold bathhouses, stoas, stadium, palaistra and large gymnasium and a 6000 seat theatre (340 – 330 BCE). These latter sporting and artistic buildings were used in the Asklepieia festival, founded in the 5th century BCE and held every four years to celebrate theatre, sport, and music. The theatre, with 2nd century CE additions resulting in 55 tiers of seats and a capacity of perhaps 12,300 spectators, would become one of, if not the, largest theatres in antiquity. Other Roman additions to the site in the 2nd century included a temple of Hygieia, a large bath building and a small odeum.

The site was destroyed in 395 CE by the Goths and the Emperor Theodosius II definitively closed the site along with all other pagan sanctuaries in 426 CE. The site was abandoned once and for all following earthquakes in 522 and 551 CE. Excavations at the ancient site were first begun in 1881 CE by the Greek Archaeological Society and continue to the present day. Today, the magnificent theatre, renowned for its acoustics, is still in active use for performances in an annual traditional theatre festival.

Ancient Corinth:

Located on the isthmus which connects mainland Greece with the Peloponnese, surrounded by fertile plains and blessed with natural springs, Corinth was an important city in Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman times. Its geographical location, helped it play a role as a center of trade, naval fleet, participation in various Greek wars, and status as a major Roman colony meant the city was, for over a millennium, rarely out of the limelight in the ancient world.

CORINTH IN MYTHOLOGY

Not being a major Mycenaean center, Corinth lacks the mythological heritage of other Greek city-states. Nevertheless, the mythical founder of the city was believed to have been King Sisyphus, famed for his punishment in Hades where he was made to forever roll a large boulder up a hill. Sisyphus was succeeded by his son Glaucus and his grandson Bellerophon, whose winged-horse Pegasus became a symbol of the city and a feature of Corinthian coins. Corinth is also the setting for several other episodes from Greek mythology such as Theseus’ hunt for the wild boar, Jason settled there with Medea after his adventures looking for the Golden Fleece, and there is the myth of Arion – the real-life and gifted kithara player and resident of Corinth – who was rescued by dolphins after being abducted by pirates.

famed for his punishment in Hades where he was made to forever roll a large boulder up a hill. Sisyphus was succeeded by his son Glaucus and his grandson Bellerophon, whose winged-horse Pegasus became a symbol of the city and a feature of Corinthian coins. Corinth is also the setting for several other episodes from Greek mythology such as Theseus’ hunt for the wild boar, Jason settled there with Medea after his adventures looking for the Golden Fleece, and there is the myth of Arion – the real-life and gifted kithara player and resident of Corinth – who was rescued by dolphins after being abducted by pirates.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The city was first inhabited in the Neolithic period (c. 5000 BCE) but became more densely populated from the 10th century BCE. The historical founders were the aristocratic descendants of King Bacchis, the Bacchiadae (c. 750 BCE). The Bacchiadae ruled as a body of 200 until in 657 BCE when the popular tyrant Cypselus took control of the city, to be succeeded by his son Periander (627- 587 BCE). Cypselus funded the building of a treasury at Delphi and set up new colonies.

From the 8th century BCE, Corinthian pottery was exported across Greece. With its innovative figure decoration, it dominated the Greek pottery market until the 6th century BCE when Attic black-figure pottery took over as the dominant style. Other significant exports were Corinthian stone and bronze wares. Corinth also became the hub of trade through the dilokos. This was a stone track with carved grooves for wheeled wagons which offered a land short-cut between the two seas and probably dates to the reign of Periander. In the Peloponnesian War, the diolkos was even used to transport triremes. Although the idea for a canal across the isthmus was first considered in the 7th century BCE and various Roman Emperors from Julius Caesar to Hadrian began surveys, it was Nero who actually began the project (67 CE). However, on the emperor’s death, the project was abandoned, not to be resumed until 1881.

From the early 6th century BCE, Corinth administered the PanHellenic games at nearby Isthmia, held every two years in the spring. These games were established in honor of Poseidon and were particularly famous for their horse and chariot races.

An oligarchy, consisting of a council of 80, gained power in Corinth (585 BCE). Concerned with the local rival, Argos, from 550 BCE Corinth became an ally of Sparta. During Cleomenes’ reign though, the city became wary of the growing power of Sparta and opposed Spartan intervention in Athens. Corinth also fought in the Persian Wars against the invading forces of Xerxes which threatened the autonomy of all of Greece.

Corinth suffered badly in the 1st Peloponnesian War, which it was responsible for after attacking Megara. Later it was also guilty of causing the 2nd Peloponnesian War, in 433 BCE. Once again though, the Corinthians, mainly as Sparta’s naval ally, had a disastrous war. Disillusioned with Sparta and concerned over Spartan expansion in Greece and Asia Minor, Corinth formed an alliance with Argos, Boeotia, Thebes, and Athens to fight Sparta in the Corinthian Wars (395-386 BCE). The conflict was fought at sea and on Corinthian territory and was yet another costly endeavor for the citizens of Corinth.

Corinth suffered badly in the 1st Peloponnesian War, which it was responsible for after attacking Megara. Later it was also guilty of causing the 2nd Peloponnesian War, in 433 BCE. Once again though, the Corinthians, mainly as Sparta’s naval ally, had a disastrous war. Disillusioned with Sparta and concerned over Spartan expansion in Greece and Asia Minor, Corinth formed an alliance with Argos, Boeotia, Thebes, and Athens to fight Sparta in the Corinthian Wars (395-386 BCE). The conflict was fought at sea and on Corinthian territory and was yet another costly endeavor for the citizens of Corinth.

Corinth became the seat of the Corinthian League, but losing a war against Philip II of Macedon (338 BCE) this ‘honor’ was a Macedonian garrison being stationed on the Acrocorinth acropolis overlooking the city.

A succession of Hellenistic kings took control of the city – starting with Ptolemy I and ending with Aratus in 243 BCE when Corinth joined the Achaean League. However, the worst was yet to come, when the Roman commander Lucius Mummius sacked the city (146 BCE).

A brighter period was when Julius Caesar took charge (in 44 BCE) and organized the agricultural land into organized plots (centurion) for distribution to Roman settlers. The city once more flourished, by the 1st century CE it became an important administrative and trade center again. In addition, following St. Paul’s visit between 51 and 52 CE, Corinth became the center of early Christianity in Greece. In a public hearing, the saint had to defend himself against accusations from the city’s Hebrews that his preaching undermined the Mosiac Law. The pro-consul Lucius Julius Gallio judged that Paul had not broken any Roman law and so was permitted to continue his teachings. From the 3rd century, CE Corinth began to decline and the Germanic tribes attacked the city.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

In Greek Corinth, there were cults to Aphrodite (protector of the city), Apollo, Demeter Thesmophoros, Hera, Poseidon, and Helios and various buildings to cult heroes, the founders of the city. In addition, there were several sacred springs, the most famous being Peirene. Unfortunately, the destruction in 146 BCE erased much of this religious past. In Roman Corinth, Aphrodite, Poseidon, and Demeter did continue to be worshipped along with the Roman gods.

The site today, first excavated in 1892 CE by the Greek Archaeological Service, is dominated by the Doric peripteral Temple of Apollo (550-530 BCE), originally with 6 columns on the façades and fifteen on the long sides. A particular feature of the temple is the use of monolithic columns rather than the more commonly used column drums. Seven columns remain standing today.

The majority of the other surviving buildings date from the 1st century CE in the Roman era and include a large forum, a temple to Octavia, baths, the Bema where St. Paul addressed the Corinthians, the Asklepeion temple to Asclepius, and a center of healing, fountains – including the monumental Peirine fountain complex (2nd century CE) – a propylaea, theatre, odeion, gymnasium, and stoas. There are also the remains of three basilicas.

Archaeological finds at the site include many fine mosaics – notably the Dionysos mosaic – Greek and Roman sculpture – including an impressive number of busts of Roman rulers.

Acrocorinth:

The steep rock of the Acrocorinth rises to the south-west of the ancient Corinth, surmounted by the fortress, also called the Acrocorinth, which was the fortified citadel of ancient and medieval Corinth and the most important fortification work in the area from antiquity until the Greek War of Independence in 1821. It is 575 m. high and its walls are a total of almost 2.000 m. in length.

The ascent to Acrocorinth – Acrocorinthos, is facilitated by a road which climbs to a point near the lowest rate on the W side. This commanding site was fortified in ancient times and its defenses  were maintained and developed during the Byzantine, Frankish, Turkish and Venetian periods. After a moat (alt. 380 m -1247 feet) constructed by the Venetians follow the first gate, built in the Frankish period (14th,c.) and the first wall 15th c. then come the second and third walls (Byzantine: on the right, in front of the third gate, a Hellenistic tower). Within the fortress we follow a path running NE to the remains of a mosque (16th c.) and then turn S until we join a path leading up to the eastern summit, on which there once stood the famous Temple of Aphrodite, worshipped here after the Eastern fashion (views of the hills of the Peloponnese and of Isthmus).

were maintained and developed during the Byzantine, Frankish, Turkish and Venetian periods. After a moat (alt. 380 m -1247 feet) constructed by the Venetians follow the first gate, built in the Frankish period (14th,c.) and the first wall 15th c. then come the second and third walls (Byzantine: on the right, in front of the third gate, a Hellenistic tower). Within the fortress we follow a path running NE to the remains of a mosque (16th c.) and then turn S until we join a path leading up to the eastern summit, on which there once stood the famous Temple of Aphrodite, worshipped here after the Eastern fashion (views of the hills of the Peloponnese and of Isthmus).

Courses of roughly dressed polygonal masonry allow us to suppose that the Acrocorinth was fortified as early as the time of the Kypselid tyranny (late 7th c. early 6th c. BCE). The surviving parts of the ancient fortifications, however, which are at many points beneath the medieval enceinte, belong mainly to the 4th c. BCE. In 146 BCE, Mummius destroyed the fortifications of the lower city and the acropolis. The destroyed sections were subsequently reconstructed during the Middle Ages, the Acrocorinth was of prime importance for the defense of the entire Peloponnese, and held out against the attacks of the barbarians. The Byzantines sporadically repaired the walls, especially after hostile raids (by the Slavs, Normans, and others), and added new fortifications on the west side of the fortress. In 1210, after a five-year siege, the Acrocorinth was captured by Otto de la Roche and Geoffroy I Villehardouin and was incorporated in the Frankish principate of Achaea. In the middle of this century, William Villehardouin extended the fortifications of the fortress, to be followed in this by the Angevin Prince John Gravina at the beginning of the 14th c.

In 1358 the Acrocorinth passed to the Florentine banker Niccolo Acciajuoli, and in 1394 to Theodoros I Palaiologos despot of Mystras. Apart from a brief occupation by the Knights of Rhodes from 1400-1404, the fortress remained in Byzantine hands until 1458, when it was captured by the Ottoman Turks. The Venetians made themselves masters of the Acrocorinth from 1687 to 1715, after which it reverted once more to the Turks until the Greek Uprising of 1821. The approach to the fortress is from the west side. The walls have an irregular shape, which was dictated by the form of the terrain and remained the same in general terms from the Classical period to modern times. Three successive zones of fortifications, with three imposing gateways, lead to the interior of the fortress. The fact that the same material was used for extensions or repairs to the walls frequently makes it difficult to distinguish the building phases or assign a date to them.

Cancellation Policy

All cancellations must be confirmed by Olive Sea Travel.

- Regarding the Multiple Day Tours: Cancellations up to 30 Days before your service date are 100% refundable.

Cancellation Policy:

-

- Licensed Tour Guides and Hotels are external co-operators & they have their own cancellation policy.

- Apart from the above cancellation limits, NO refunds will be made. If though, you fail to make your appointment for reasons that are out of your hands, that would be, in connection with the operation of your airline or cruise ship or strikes, extreme weather conditions or mechanical failure, you will be refunded 100% of the paid amount.

- If your cancellation date is over TWO (2) months away from your reservation date, It has been known for third-party providers such as credit card companies, PayPal, etc. to charge a levy fee usually somewhere between 2-4%.

- Olive Sea Travel reserves the right to cancel your booking at any time, when reasons beyond our control arise, such as strikes, prevailing weather conditions, mechanical failures, etc. occur. In this unfortunate case, you shall be immediately notified via the email address you used when making your reservation and your payment WILL be refunded 100%.

Recommended for you