5 days

Private Tour

English

UP TO 12 GUESTS

5 Days TOP Highlights in Mainland and Islands of Greece

Got a Question?

Contact UsHighlights

Island hopping & Athens private tour

Day 1st:

- Acropolis Hill – Propylaea – Parthenon – Erechtheion – Temple of Athena Nike

- Dionysus Theatre – Herodion Odeon

- Temple of Zeus – Arch of Hadrian

- Old Olympic Stadium

- Parliament – Changing of the Guards

- Academy of science – Athens University – National Library

- Ancient Agora

- New Acropolis Museum

- Lycabettus Hill

- Plaka – The Old City

Overnight: Athens

Day 2nd:

- Levadia

- Distomo – Hosios Loukas

- Arachova Village

- Village of Delphi

- The Oracle of Delphi

- Museum of Delphi

- Sanctuary Athena Pronea – Gymnasium

Overnight: Athens

Day 3rd:

- Hydra Island

- Poros Island

- Aegina Island – Afaia Temple

Overnight: Athens

Day 4th:

- Athenian Riviera

- Glyfada – Voula

- Vouliagmeni – Varkiza – Anavissos

- Cape Sounion

- Poseidon’s Temple

Overnight: Athens

Day 5th:

- Corinth Canal

- Ancient Corinth – Temple of Apollo

- Acrocorinth

- Ancient Nemea

- Nemea Wine Roads (Winery)

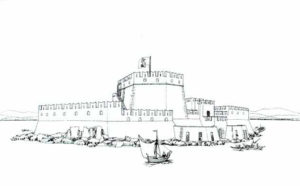

- The picturesque town of Nafplio – Palamidi – Bourtzi

- Drive to Athens

Itinerary

1st Day:

Sightseeing in Athens starts with the hill of Acropolis which will make your day. On the historical hill, you will have the opportunity to see the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, the Temple of the Athena Nike, the monumental gateway (Propylaea), the Erechtheum and of course the famous Parthenon, the main temple dedicated to the virgin goddess Athena.

After the Acropolis, we will head towards the Temple of Zeus by way of Hadrians Arch and from there we will visit Panathenaic Stadium where the first modern Olympic Games were held in 1896. Next driving alongside the National Garden, we will see the changing of the guard (Evzones) in front of the old palace, which is today Parliament House, above the central square of Athens.

After that, we will drive to Panepistimiou Street one of the most historical streets of Athens to see numerous neoclassical buildings still standing and dating back to the late 19th century but more importantly we’ll see the architectural trilogy of Athens (The Academy – The University – The National Library). Then moving into the historical center of the city we will drive up the highest hill of Athens, Lycabettus Hill, where you’ll have the best panoramic view of the city, from the hill of Acropolis to the Aegean Sea. You will be feeling hungry by now so the next stop is a traditional Greek tavern with authentic Greek dishes.

After lunch, we will visit the two historically old neighborhoods of Athens, Plaka, and Monastiraki, where the famous Andrianou Street is located, and be ending at the flea market (shopping area). Where you will also visit the Roman Agora and the Tower Of The Winds and let’s not forget the Ancient Greek Agora which is considered the birthplace of democracy, philosophy and free speech. In the ancient Greek Agora, you will visit the Temple of Hephaestus (the best-preserved temple in Greece standing largely as built) and a small museum house under the Portico of Attalos. Eventually bringing us to the New Acropolis Museum. A brand new museum opened in 2009 to host all the findings that have been excavated on the hill of Acropolis and its slopes also known as the museum of the senses. It is counted as one of the best museums in the world.

2nd Day:

This is a great opportunity to visit one of the most renowned sites in Greece in one day. The Delphi day tour starts with a drive on the national highway towards northern Greece passing by the plane of Thieves and the city of Levadia. Then we will be on the slopes of Mount Parnassus before reaching Delphi. Our first stop is going to be the monastery of Hosios Loukas, which represents the second golden age of Byzantine art (11th -12th century) in particular its golden mosaic decoration and fine architecture.

After spending some time in this area of serenity we will drive to the site of Delphi, an ancient Greek sanctuary with a PanHellenic character dedicated to the God Apollo. It functioned as an Oracle and was considered ‘the naval’, the center of the world and is today a symbol of Greek cultural unity. The scenic location allows you to have a view of the Greek mountains and two more sites the Gymnasium and the secondary sanctuary of Athena Pronea. In the site, you will visit the Temple of Apollo where Pythia spoke to the oracles, the theater, and the stadium. While in the museum you will be able to see the famous charioteer and Gold Ivory statue.

After the site we will have our lunch at the modern village of Delphi with a view of the mountains of Fokis and our last destination will be the village of Arachova. A mountainous village built on a cliff 900 m above sea level very close to the Parnassus ski resort. It’s the mainland’s answer to Mykonos. After some free time for shopping and wandering around we will have a pleasant drive back to Athens.

3rd Day:

We will drive to the port to start your cruise. You’ll depart Athens under the morning sun and enjoy a delicious, optional breakfast, if you choose, from our menu. As you cruise the legendary waters of the historic Saronic Gulf, our first island destination, is Hydra. The charming atmosphere of the island has seduced many international jet setters and has been a retreat for famous personalities! Elegant stone mansions, narrow alleys, donkeys walking around, churches, little shops, and a picturesque waterfront set the scene of an island fairytale!

Depart Hydra and cruise to Poros, a quiet and beautiful green island, noted for its pleasant beaches and the fragrant aroma of lemon carried by a gentle wind from its many groves. The boat will be at Poros for about 40 minutes leaving you enough time to admire the graphic setting of the island’s Chora.

Cruise to Aegina and discover the island’s brilliant cultural heritage. You’ll have about 2 hours to discover the island’s beauties either on your own or through one of our guided tours.

A visit to the Temple of Afaia is an unforgettable excursion. The temple is the focal point of the area of the sanctuary, founded in ancient Aegina to commemorate the Minoan deity Afaia, daughter of Zeus and Carme. The temple is in the Dorian style and is considered by many to be the model the Parthenon in Athens.

Return to Athens in the early evening and enjoy an amazing view of the Attica sky at sunset from our Sun Deck and Live Greek Folk Dance Show that will accompany you for about 1.5 – 2 hours until you reach Attica’s port.

4th Day:

The immense blue of the Aegean Sea and the extraordinary landscape make Greece ideal for honeymooners but Cape Sounio has its own special atmosphere that  awakens the romantic in everyone. A place where you can share enchanted precious moments with your significant other.

awakens the romantic in everyone. A place where you can share enchanted precious moments with your significant other.

We will begin by driving along the Athenian Riviera, with the Aegean piercing through you. Progressively passing the uptown suburbs (Glyfada, Voula, Vouliagmeni, Varkiza). We will stop at the picturesque peninsula of Vouliagmeni. This is the most expensive piece of land in the whole of Greece with its majestic mineral water spa-like. Its mild climate and water temperature makes it an all-year-round possibility. The most expensive hotel in Attica can be found here, just to explain how special this destination is.

Continuing along the dreamy coast, taking in the Aegean, the Saronic Gulf and its small islands we will deliver you to the magical Cape Sounio with its sunset that is to die for. Crowning the cape is the temple of Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea. It is surrounded by the remains of its fortifications, gateway, and houses. Close by are also the remains of Athena Souniada. This precious site will be hard to top off but you will enjoy an idyllic dinner by the sea. A true romantic can never pass up a chance to visit Sounio.

5th Day:

This day is for those who are not only interested in the imposing archaeological sites of the Greek countryside but would also like to taste the famous Greek wine of Nemea by visiting one of its wineries. The region has produced the most qualitative and tasteful wine in Greek for thousands of years.

The tour starts with a drive along the coast, on the way you will view some Greek seaside villages and the island of Salamis (where the historical naval battle took place between the Athenians and the Persians). Our first stop the Corinth Canal. Opened in 1892 separating the Peloponnese peninsula from the rest of Greece and connecting the Saronic Gulf to the Corinthian Sea. You will have time to walk across on a pedestrian bridge to admire the canal closer, (if you’re game,) on some days bungee jumping is an option.

Moving on we will continue to Ancient Corinth. The city dominated by the hill of Acrocorinth and the old Castle, the oldest and largest castle in southern Greece. The site located at the foot of the hill includes the Roman Agora of Corinth, the temple of god Apollo and a small museum. Apart from its archaeological and historical interest Ancient Corinth is also one of the most popular religious destinations in Greece as this was where the Apostle Paul preached Christianity, was judged by the tribunal in the Agora and established the best organized Christian church of that period.

Our Next stop will be the site of Ancient Nemea. Nemea is mainly known for the Nemean Games the ancient Greek stadium and the Temple Of Zeus but also for the vineyards. Nemea has the most wineries in Greece as grape growing has been a tradition here since ancient times. In the site apart for the museum and the sanctuary, the stadium  makes the difference. One of the best-preserved stadiums, located on a higher level still preserves the tunnel through which the athletes entered the stadium.

makes the difference. One of the best-preserved stadiums, located on a higher level still preserves the tunnel through which the athletes entered the stadium.

After the visit to the site, we will head towards one of the Nemean wineries. Driving through the grape yards of the largest wine production zone in Greece, we will visit one of the best wineries. People will gladly give you a small tour showing you the grape yards, the storage barrels, explaining to you the procedure that takes place until the bottling. In the end, you will be offered to taste some of their best varieties while having a view of the Nemean Valley.

Lastly, we will drive towards the city of Nafplio for our last stop, considered the most scenic city, it functioned as the capital of Greece until 1834. It offers you an outstanding combination of fortresses and castles (Palamidi), Bourtzi, a huge port opened to the Aegean Sea and the unique architecture of the old city of Nafplion revealing Venetian, neoclassical and oriental elements. After walking in the idyllic old city we will stop for lunch at a traditional tavern by the sea, and drive up to the castle of Acronafplia for a panoramic view of Nafplio. Then we will start our way back following the eastern coast of the Peloponnese peninsula to reach Athens again.

After traveling with us you will have seen the ‘real Greece’ and met ‘real people’. We are content to show you the Greece we know and love. Avoiding the tourist traps. Being a traveler, not a tourist.

Inclusions - Exclusions

Inclusions:

-

Professional Drivers with Deep knowledge of history. [Not licensed to accompany you in any site.]

-

Hotel pickup and drop-off

-

Transport by private vehicle

- Cruise-ship ticket VIP class

- Excursion in Aegina island

- Wine Tasting

- Bottled water

Exclusions:

- Entrance Fees

- Accommodation with breakfast

- Licensed Tour guide upon request depending on availability (Additional cost)

- Airport Pick Up and drop-off (Additional cost)

- Food & Drinks

Entrance Fees

ADMISSION FEES FOR SITES:

Summer Period: 171€ per person

(1 April – 31 October)

Acropolis: 30€ (08:00- 20:00)

Temple of Zeus: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Ancient Agora: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Acropolis Museum: 20€ (Monday: 08:00- 16:00/ Tuesday- Sunday: 09:00- 20:00/ Friday: 08:00- 22:00)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 20:00)

Hosios Loukas Monastery: 10€ (08:00- 15:30)

Afaia Temple Aegina: 6€ (10.00-17.30)

Temple of Poseidon: 20€ (08:00- sunset, about 20:00)

Ancient Corinth: 15€ (08:00- 20:00)

Ancient Nemea: 10€ (08:00- 17:00)

Winter Period: 171€ per person

(1 November – 31 March)

Acropolis: 30€ (08:00- 17:00)

Temple of Zeus: 20€ (08:00- 17:00)

Ancient Agora: 20€ (08:00- 17:00)

Acropolis Museum: 20€ (Monday- Thursday: 08:00- 20:00/ Friday: 09:00- 22:00/ Saturday- Sunday: 09:00- 20:00)

Delphi: 20€ (08:00- 15:30)

Hosios Loukas Monastery: 10€ (08:00- 15:30)

Afaia Temple Aegina: 6€ (10.30-17.30)

Temple of Poseidon: 20€ (09:30- sunset, about 17:00)

Ancient Corinth: 15€ (08:00- 15:30)

Ancient Nemea: 10€ (08:00- 15:30, Tuesday closed)

Free admission days:

- 6 March (in memory of Melina Mercouri)

- 18 April (International Monuments Day)

- 18 May (International Museums Day)

- The last weekend of September annually (European Heritage Days)

- Every first and third Sunday from November 1st to March 31st

- 28 October

Holidays:

- 1 January: closed

- 25 March: closed

- 1 May: closed

- Easter Sunday: closed

- 25 December: closed

- 26 December: closed

Free admission for:

- Children & young people up to the age of 25 from EU Member- States

- Children & young people from up to the age of 18 from Non- European Union countries

- Persons over 25 years, being in secondary education & vocational schools from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers during the visits of schools & institutions of Primary, Secondary & Tertiary education from EU Member- States

- People entitled to Social Solidarity income & members depending on them

- Persons with disabilities & one escort (only in the case of 67% disability)

- Refugees

- Official guests of the Greek State

- Members of ICOM & ICOMOS

- Members of societies & Associations of friends of State Museums & Archaeological sites

- Scientists licensed for photographing, studying, designing or publishing antiquities

- Journalists

- Holders of a 3- year Free Entry Pass

Reduced admission for:

-

- Senior citizens over 65 from Greece or other EU member-states, during

the period from 1st of October to 31st of May - Parents accompanying primary education schools visits from EU Member- States

- Escorting teachers of educational visits of schools & institutions of primary, secondary & tertiary education from non European Union countries

Reduced & free entrance only upon presentation of the required documents

- Senior citizens over 65 from Greece or other EU member-states, during

Amenities for the physically challenged:

Elevator available for wheelchairs, people with diminished abilities and any parent attending two or more infants on her/his own. The elevator is located about 350 m. far from the main entrance of the archaeological site.

Users of the elevator should contact in advance for details and terms (+30 210 3214172). The facility is not available during extreme weather conditions and strong winds.

History

Acropolis:

The Acropolis hill (acro – edge, polis – city), so-called the “Sacred Rock” of Athens, is the most important site of the city and constitutes one of the most recognizable monuments of the world. It is the most significant reference point of ancient Greek culture, as well as the symbol of the city of Athens itself as it represents the apogee of artistic development in the 5th century BCE. During Perikles’ Golden Age, ancient Greek civilization was represented in an ideal way on the hill and some of the architectural masterpieces of the period were erected on its ground.

Propylaea:

The Propylaea is the monumental entrances to the sacred area dedicated to Athena, the patron goddess of the city. Built by the architect Mnesicles with Pentelic marble, their design was avant-garde. To the south-west of the Propylaea, on a rampart protecting the main entrance to the Acropolis, is the Ionian temple of Apteros Nike or Wingless Victory.

Parthenon:

The Parthenon. It is the most important and characteristic monument of the ancient Greek civilization and still remains its international symbol. It was dedicated to Athena Parthenos (the Virgin), the patron goddess of Athens. It was built between 447 and 438 B.C.E. and its sculptural decoration was completed in 432 B.C.E. The construction of the monument was initiated by Perikles, the supervisor of the whole work was Pheidias, the famous Athenian sculptor, while Iktinos (or Ictinus) and Kallikrates (Callicrates) were the architects of the building. The temple is built in the Doric order and almost exclusively of Pentelic marble. It is peripheral, with eight columns on each of the narrow sides and seventeen columns on each of the long ones. The central part of the temple, called the cella, sheltered the famous chryselephantine cult statue of Athena, made by Pheidias. The rest of sculptural decoration, also by Phidias, was completed by 432 BCE. The sculptural decoration of the Parthenon is a unique combination of the Doric metopes and triglyphs on the entablature, and the Ionic frieze on the walls of the cella. The metopes depict the Gigantomachy on the east side, the Amazonomachy on the west, the Centauromachy on the south, and scenes from the Trojan War on the north. The Parthenon, the Doric temple, the pinnacle of Pericles’ building program, is beyond question the building most closely associated with the city of Athens, a true symbol of ancient Greek culture and its universal values.

The New Acropolis Museum:

As you enter the museum grounds, look through the plexiglass floor to see the ruins of an ancient Athenian neighborhood, which were artfully incorporated into the museum design after being uncovered during excavations. This dazzling modernist museum at the foot of the Acropolis’ southern slope showcases its surviving treasures still in Greek possession. While the collection covers the Archaic and Roman periods, the emphasis is on the Acropolis of the 5th century BCE, considered the apotheosis of Greece’s artistic achievement. The museum cleverly reveals layers of history, floating over ruins with the Acropolis visible above, showing the masterpieces in context. The surprisingly good-value restaurant has superb views (and reviews); there’s also a fine gift shop.

The Temple of Zeus:

This marvel is right in the center of Athens. It is the largest temple in Greece. Building began in the 6th century BCE by Peisistratos, (but it was abandoned for lack of funds). Various other leaders attempted to finish it, but it was left to Hadrian to complete the work in AD 131 – taking more than 700 years in total to build. The temple is impressive for the sheer size of it. Originally it had 104 Corinthian columns (17 m high and with a base diameter of 1.7 m). Unfortunately, only 15 remains (the fallen one was blown down in a gale in 1852). Hadrian also put up a colossal statue of Zeus (in the cella) and because he was such a modest fellow he placed an equally large one of himself next to it.

Hadrian’s Arch:

The Roman emperor Hadrian had a great affection for Athens. Although he did his fair share of spiriting its classical artwork to Rome, he also embellished the city with many monuments influenced by classical architecture. His arch is a lofty monument of Pentelic marble that stands where busy Leoforos Vasilissis Olgas and Leoforos Vasilissis Amalias meet. Hadrian erected it in AD 132, probably to commemorate the consecration of the Temple of Olympian Zeus. The inscriptions show that it was also intended as a dividing point between the ancient and Roman city. The northwest frieze reads, ‘This is Athens, the ancient city of Theseus’, while the southeast frieze states, ‘This is the city of Hadrian, and not of Theseus’.

The Old Olympic Stadium/ Panathenaic Stadium:

The grand Panathenaic Stadium lies between two pine-covered hills(between the neighborhoods of Mets and Pangrati). It was originally built in the 4th century BCE as a venue for the Panathenaic athletic contests. It’s said that at Hadrian’s inauguration in AD 120, 1000 wild animals were sacrificed in the arena. Later, the seats were rebuilt in Pentelic marble by Herodes Atticus. There are seats for 70,000 spectators, a running track and a central area for field events. After hundreds of years of disuse, the stadium was completely restored in 1895 (by a wealthy Greek benefactor Georgios Averof) to host the first modern Olympic Games the following year. It’s a faithful replica of the original Panathenaic Stadium. It made a stunning backdrop to the archery competition and the marathon finish during the 2004 Olympics. It’s occasionally used for concerts and public events, and the annual Athens marathon finishes here.

The grand Panathenaic Stadium lies between two pine-covered hills(between the neighborhoods of Mets and Pangrati). It was originally built in the 4th century BCE as a venue for the Panathenaic athletic contests. It’s said that at Hadrian’s inauguration in AD 120, 1000 wild animals were sacrificed in the arena. Later, the seats were rebuilt in Pentelic marble by Herodes Atticus. There are seats for 70,000 spectators, a running track and a central area for field events. After hundreds of years of disuse, the stadium was completely restored in 1895 (by a wealthy Greek benefactor Georgios Averof) to host the first modern Olympic Games the following year. It’s a faithful replica of the original Panathenaic Stadium. It made a stunning backdrop to the archery competition and the marathon finish during the 2004 Olympics. It’s occasionally used for concerts and public events, and the annual Athens marathon finishes here.

The Changing of the Guard:

Although the guards change hourly, there is a big ceremony once a week. These guards, the Evzones, stand motionless at the tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Getting into this unit is an honor, and they have to be over 6 ft. tall. They wear white tights, a white skirt, a white blouse with full sleeves, an embroidered vest, red cap, and shoes with big pom-poms. but don’t let the outfit fool you, these guys are the best of the best. The uniform is based on the clothing of the Klephts, mountain fighters who fought the Turks from the 15th Century until Greek independence in the 19th Century.

The Academy of Science:

The Academy Building constitutes one of three parts in an “architectural trilogy”. It was founded with the Constitutional Decree of March 18th, 1926, as an Academy of Sciences, Humanities and Fine Arts. The same Decree appointed its first members, who were all eminent representatives of the scientific, intellectual and artistic circles of that era. Designed in 1859, by the Danish architect Theophil Hansen (1813-1891, the younger brother of the University’s architect, Christian Hansen). It is considered the most important work of Hansen and is regarded by some experts as the most beautiful neoclassic building worldwide. The architect’s source of inspiration was the classical architecture of fifth century B.C.E. Athens, as portrayed in the monuments of the Acropolis. In particular, Hansen imitated the Ionian rhythm that dominates the building of the Academy, from the Erechtheion monument. The essence of all ancient Greek tradition can be found in the building’s sculptural and pictorial decoration; simultaneously the character of that era’s Hellenism and its visions for the future are also expressed.

The University of Athens:

The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens is the largest state institution of higher learning in Greece, and among the largest universities in Europe. The splendid Athens University was designed by the Danish architect Christian Hansen and completed in 1864. It was the first of the Architectural Trilogy to be built. It still serves as the university’s administrative headquarters. To its left is the Athens Academy, designed by Hansen’s brother Theophile. Unfortunately, neither is open to the public.

The National Library:

The National Library of Greece was built at the end of the 19th century, as the last of the Architectural Trilogy of Athens, a group of three neoclassical buildings which also includes the Academy and the University. The building was designed by Theophil Hansen, a Danish architect who had studied classical architecture in Vienna and Athens. (He had also previously worked on the University – together with his older brother Christian, as well as on the Zappeion and the Academy of Athens). Construction of the National Library started in 1887 and was completed fifteen years later. Theophil Hansen died in 1891 and would never see his building completed. The National Library was designed as a Doric temple flanked by two wings and built almost entirely with Pentelic marble. The design of the Doric building was based on that of the Propylaea on the Acropolis. (It is devoid of any sculptural ornamentation; even the tympanum is left undecorated). Two wide winding staircases lead to the entrance of the “temple”. The statue standing between the staircases shows one of the benefactors of the library, the merchant Panaghis Athanassiou Vallianos. The building houses a large collection of books, maps, newspapers, and manuscripts in Greek and other languages. Most interesting is the collection of Greek manuscripts, some of which are more than 1400 years old.

Ancient Agora:

In the heart of ancient Athens was the Agora, the lively, crowded focal point of administrative, commercial, political and social activity. Socrates talked about his philosophy here, and in AD 49 St Paul came here to speak on Christianity. The site was occupied without interruption throughout the city’s history. It was used as a residential and burial area as early as the Late Neolithic Period (3000 BCE) but it was first developed as a public site in the 6th century BC (the time of Solon). The Agora was devastated by the Persians in 480 B.C.E., but a new one was built in its place almost immediately. It was flourishing by Pericles’ time and continued to do so until AD 267 when it was destroyed by the Herulians (a Gothic tribe from Scandinavia). The Turks built a residential quarter on the site, but this was demolished by archaeologists after Independence and later excavated to classical and, in parts, Neolithic levels. The site today is a grand, refreshing break, with beautiful monuments and temples and a fascinating museum. The museum is housed in the Stoa of Attalos, and its exhibits are connected with the Athenian democracy. The collection of the museum includes clay, bronze and glass objects, sculptures, coins and inscriptions from the 7th to the 5th century B.C.E., as well as pottery of the Byzantine period and the Turkish occupation.

The Roman Agora:

The entrance to the Roman Agora is through the well-preserved Gate of Athena Archegetis, flanked by four Doric columns. It was financed by Julius Caesar and erected sometime during the 1st century AD. In it is the Tower of Winds. The well-preserved, extraordinary Tower of the Winds was built in the 1st century B.C.E. by a Syrian astronomer named Andronicus. The octagonal monument of Pentelic marble is an ingenious construction that functioned as a sundial, weather vane, water clock, and compass. Each side of the tower represents a point of the compass, with a relief of a floating figure representing the wind associated with that particular point. Beneath each of the reliefs are faint sundial markings. The weather vane, which disappeared long ago, was a bronze Triton that revolved on top of the tower. The Turks allowed dervishes to use the tower. The rest of the ruins are quite bare. To the right of the entrance are foundations of a 1st-century public latrine. In the southeast area are foundations of a propylon (fortified tower) and a row of shops.

The Hill of Lycabettus:

The name Lykavittus appears in various legends. Popular stories suggest it was once the refuge of wolves, (Lycos in Greek), which is possibly the origin of its name (means “the one [the hill] that is walked by wolves”). Mythologically, Lycabettus is credited to Athena, who created it when she dropped a mountain she had been carrying from Pallene for the construction of the Acropolis.

There is a path that leads to the summit Alternatively, take the funicular railway, or Telerik or a drive up to the top. Don’t try to walk up (pilgrims used to, but it’s an Everest for the faithless). The panorama from the top is priceless – all the way to Mount Parnes in the north, west to Piraeus and the Saronic Gulf, with the Acropolis sitting like a ruminative lion halfway to the sea. There’s also a cafe /restaurant up there. Perched on the summit is the little Chapel of Agios Georgios, floodlit like a beacon over the city at night. The open-air Lykavittos Theatre, northeast of the summit, hosts concerts in summer. And many famous artists have performed there.

Plaka – The Old Town:

Stroll through the streets of Plaka – the city’s Old Town. Sprawled over the side of Athens’ Acropolis, this historical neighborhood comprises a maze of cobbled streets lined with Neoclassical architecture, Byzantine churches, and busy independent shops. On the northernmost streets of Plaka is the area is known as Anafiotika — an idyllic cluster of whitewashed houses that are reminiscent of buildings in the Greek islands. Admire Anafiotika’s pretty Cycladic architecture, built by 19th-century workers who emigrated here from Anafi Island. It’s thought the workers were homesick for their native island life, so painted the buildings bright white to remind them of Anafi. Feel like an islander on the mainland.

Hosios Loukas:

The World Heritage–listed monastery, Moni Osios Loukas, is 23 km southeast of Arahova, between the villages of Distomo and Kyriaki. The monastic complex includes two churches. Its principal  church contains some of Greece’s finest Byzantine frescoes. Modest dress is required (no shorts). Nearby is the smaller 10th-century Agia Panagia (Church of the Virgin Mary). The monastery is dedicated to a local hermit who was canonized for his healing and prophetic powers.

church contains some of Greece’s finest Byzantine frescoes. Modest dress is required (no shorts). Nearby is the smaller 10th-century Agia Panagia (Church of the Virgin Mary). The monastery is dedicated to a local hermit who was canonized for his healing and prophetic powers.

The interior of the larger church, Agios Loukas, is a glorious symphony of marble and mosaics, with icons by Michael Damaskinos, the 16th-century Cretan painter. In the main body of the church, the light is partially blocked by the ornate marble window decorations, creating striking contrasts of light and shade. Walk around the corner to find several fine frescoes that brighten up the crypt where St Luke is buried.

Delphi:

Delphi was an important ancient Greek religious sanctuary sacred to the god Apollo. Located on Mt. Parnassus near the Gulf of Corinth, the sanctuary was home to the famous oracle of Apollo which gave cryptic predictions and guidance to both city-states and individuals. In addition, Delphi was also home to the PanHellenic Pythian Games.

MYTHOLOGY & ORIGINS:

The site was first settled in Mycenaean times in the late Bronze Age (1500-1100 BCE) but took on its religious significance from around 800 BCE. The original name of the sanctuary was Python after the snake which Apollo was believed to have killed there. Offerings at the site from this period include small clay statues (the earliest), bronze figurines, and richly decorated bronze tripods.

Delphi was also considered the center of the world, for in Greek mythology Zeus released two eagles, one to the east and another to the west, and Delphi was the point at which they met after encircling the world. This fact was represented by the omphalos (or navel); a dome-shaped stone which stood outside Apollo’s temple and which also marked the spot where Apollo killed the Python.

APOLLO’S ORACLE:

APOLLO’S ORACLE:

The Oracle of Apollo at Delphi was famed throughout the Greek world and even beyond. The Oracle – the Pythia or priestess – would answer questions put to her by visitors wishing to be guided in their future actions. The whole process was a lengthy one, usually taking up a whole day and only carried out on specific days of the year. First, the priestess would perform various actions of purification such as washing in the nearby Castalian Spring, burning laurel leaves and drinking holy water. Next an animal – usually a goat – was sacrificed. The party seeking advice would then offer a pelanos – a sort of pie – before being allowed into the inner temple where the priestess resided and gave her pronouncements, possibly in a drug or natural gas-induced state of ecstasy.

Perhaps the most famous consultant of the Delphic oracle was Croesus, the fabulously rich King of Lydia who, when faced with a war against the Persians, asked the oracle’s advice. The Oracle stated that if Croesus went to war then a great empire would surely fall. Reassured by this, the king took on the mighty Cyrus. However, the Lydians were overpowered at Sardis and it was the Lydian empire which fell, a lesson that the oracle could easily be misinterpreted by the unwise or over-confident.

PANHELLENIC GAMES:

Delphi, as with the other major religious sites of Olympia, Nemea, and Isthmia, held games to honor various gods of the Greek religion. The Pythian Games of Delphi began sometime between 591 and 585 BCE and were initially held every eight years, with the only event being a musical competition where solo singers accompanied themselves on a kithara to sing a hymn to Apollo. Later, more musical contests and athletic events were added to the programme, and the games were held every four years with only the Olympic Games being more important. The principal prize for victors in the Games was a crown of laurel or bay leaves.

The site and games were managed by the independent Delphic amphictyony – a council with representatives from various nearby city-states – which asked for taxes, collected offerings, invested in construction programes, and even organized military campaigns in the Four Sacred Wars, fought to remedy sacrilegious acts against Apollo committed by the states of Crisa, Phocis, and Amphissa.

ARCHITECTURE:

The first temple in the area was built in the 7th century BCE and was a replacement for less substantial buildings of worship which had stood before it. The focal point of the sanctuary, the Doric temple of Apollo, was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 548 BCE. A second temple, again Doric in style, was completed in 510 BCE. Measuring some 60 by 24 meters, the facade had six columns whilst the sides had 15. This temple was destroyed by the earthquake in 373 BCE and was replaced by a similarly sized temple in 330 BCE. This was constructed of porous stone coated in stucco. Marble sculpture was also added as decoration along with Persian shields taken at the Battle of Marathon. This is the temple which survives, although only partially, today.

Other notable constructions were the theatre (with capacity for 5,000 spectators), temples to Athena (4th century BCE), a tholos with 13 Doric columns ( 580 BCE), stoas, a stadium (with capacity for 7,000 spectators), and around 20 treasuries, which were constructed to house the votive offerings and dedications from city-states all over Greece. Similarly, monuments were also erected to commemorate military victories and other important events. For example, the Spartan general Lysander erected a monument to celebrate his victory over Athens at Aegospotami. Other notable monuments were the great bronze Bull of Corcyra (580 BCE), the ten statues of the kings of Argos (369 BCE), a gold four-horse chariot offered by Rhodes, and a huge bronze statue of the Trojan Horse offered by the Argives (413 BCE). Lining the sacred way, from the sanctuary gate up to the temple of Apollo, the visitor must have been greatly impressed by the artistic and literal wealth on display. Alas, in most cases, only the monumental pedestals survive of these great statues, silent witnesses to a lost grandeur.

DEMISE:

In 480 BCE the Persians attacked the sanctuary and in 279 BCE the sanctuary was attacked again, this time by the Gauls. During the 3rd century BCE, the site came under the control of the Aitolian League. In 191 BCE Delphi passed into Roman hands; however, the sanctuary and the games continued to be culturally important in Roman times, in particular under Hadrian. The decree by Theodosius in 393 CE to close all pagan sanctuaries resulted in Delphi’s gradual decline. A Christian community dwelt at the site for several centuries until its final abandonment in the 7th century CE.

The site was ‘rediscovered’ with the first modern excavations being carried out in 1880 CE by a team of French archaeologists. Notable finds were splendid metope sculptures from the treasury of the Athenians (490 BCE) and the Siphnians (525 BCE) depicting scenes from Greek mythology. In addition, a bronze charioteer in the severe style (480-460 BCE), the marble Sphinx of the Naxians (560 BCE), the twin marble archaic statues – the kouroi of Argos (580 BCE) and the richly decorated omphalos stone (330 BCE) – all survive as testimony to the cultural and artistic wealth that Delphi had once enjoyed.

Hydra:

There is evidence from the 2nd half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Fragments of vases, tools, and the head of an idol have been found. The island lost its population during the Latin Empire of Constantinople as its inhabitants fled the pirate depredations. From 1204 to 1821, it belonged to the Venetians or it was part of the Ottoman Empire. Since 1460, Arvanites are settled on the island, refugees from Peloponnese, and create the modern town port.

Ottoman era: period of commercial and naval strength

Its naval and commercial development began in the 17th century, and its first school for mariners was established in 1645. The first Hydriot vessel was launched in 1657. However, the conflict between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire limited the island’s development. From the 17th century, Hydra began to take a greater importance because of its trading strength.

During the 18th century the Hydriots traded in the Aegean, going as far as Constantinople. In 1757 they launched a vessel of 250 tons which enabled Hydra to become an important commercial port. By 1771, there were up to 50 vessels. Ten years later, the island had 100 vessels.

However, the Ottoman Empire constrained Hydra’s economic success. Heavy tariffs and taxes limited the development. The Ottoman administration limited free trade, permitting only Ottoman vessels to have access to the Black Sea. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca changed this. Russia gained the right to protect the Empire’s Orthodox Christians. The Hydriots began to sail under the Russian flag. Hydra entered its commercial era. Hydriot vessels carried goods between Southern Russia and the Italian ports. From 1785, the Hydriot shippers began to engage in commerce.

The plague of 1792 killed a large part of the population, so the town was almost completely abandoned. By the end of the 18th century, Hydra had become quite prosperous, with its vessels trading.

Greek War of Independence and later decline

In the 19th century, Hydra was home to 125 boats and 10,000 sailors. The mansions of the sea captains are a testament to the prosperity of the island. In April 1821, when Greeks proclaimed Hydra’s adherence to the independence struggle, they met strong opposition from island leaders who were reluctant to lose the privileged position they had under Ottoman rule. Hydra eventually joined the cause of independence, and its contribution of 150 ships against the Turks played a critical role.

With the creation of the Greek state, the island gradually lost its maritime position in the Mediterranean. The main reason was that with the creation of the Greek state, Hydra’s fleet lost the privileges and that the traditional families failed to foresee the benefits of participating in the steam ship revolution, putting them at a disadvantage of the new shipping companies. Once again, many inhabitants abandoned Hydra, leaving behind their large mansions and beautiful residences. The mainstay of the island’s economy became fishing for sponge. By World War II, the Hydriots were again leaving the island.

Poros:

Poros was divided in two islands during the antiquity: Sphairia and Kalavria. Sphairia consisted of the area of the modern island which includes its current capital. During the period of Mycenaean dominance (1400-1100 BC) Kalavria was quite powerful and the most important naval base. The city-state of Kalavria was home to an asylum dedicated to Poseidon, the ruins of which are still accessible on a hilltop close to the town.

In 273 BC, the last explosion of the Methana volcano dramatically changed the morphology of Poros and the wider region.

During the Roman period Poros was part of the Roman Empire. In Byzantine times, it was often raided by the pirates that dominated the Aegean Sea. In 1484 the Venetians occupied Poros and used it as a strategic port in their sea battles with the Ottomans. Venetian rule ended in 1715 when the Ottoman Period began. Shipping and commerce were the inhabitants’ main activities.

Poros had an important role during the Greek Revolution in 1821, due to its strategic position. The Greek revolutionary leaders often met in Poros to discuss and plan their future actions. The first Greek naval base was established in Poros in 1828 and remained there until 1878.

With the Treaty of Kuchuk Kainarji, Russia secured free shipping for its navy, throughout the waters of the Ottoman Empire. As Russian naval activity grew, need arose for a supply station, and land was acquired at the edge of Poros town. The number of Russian residents of Poros increased and even a Russian school was established. Then as Russian naval activity declined, so did the base. The ruins, in elaborately carved stone, were listed as protected architectural monuments in 1989.

In the beginning of the 20th century, among the activities of the Poros’ inhabitants were agriculture (mainly wheat, grapevines and olives), livestock, fishing and shipping.

Aegina:

According to ancient mythology, Aegina owes its name to the nymph Aegina, daughter of the river god Asopus, who Zeus seduced and took on the island of Aegina, then called Oenone. There she gave birth to Aecus, the first king of the island and grandfather of the famous Trojan hero, Achilles. Aecus renamed the island Aegina, in honor of his mother. Archaeological findings in Kolona, near the island’s capital, prove that the history of Aegina starts from the Neolithic period, as the island has been inhabited since 3,000 BC.

Aegina saw its economical and naval power grow around the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, developing its trade and carrying with its own ships local products to the Cyclades, Crete, and to the Greek Mainland. To honor the gods for this prosperity, the inhabitants built temples to them. In Kolona, there are also the remains of an ancient Temple to Apollo, while in the center of the island, among mountainside, there is the temple of Ellanios Zeus.

The island’s glory exploded during the 6th and 7th century BC when its naval power reached the zenith of its development, its trade was at its best, extending even until Egypt and Phoenicia and because Aegina was the first part of Greece, even of Europe, to mint coins: the famous silver turtle coins, since the symbol of the island was the turtle. In these centuries, the island was very wealthy: those were the golden times of Aegina.

The powerful fleet of the island made a major contribution during the Battle of Salamis against the Persians, on the side of the Greeks. After the Persian defeat, Aegina continued to flourish, and its inhabitants built the superb Temple of Aphaia. Unfortunately, things changed: the Athenians did not see the economic, social and naval glory of Aegina with a good eye. They attacked it in 459 BC and forced it to pull down its city walls and surrender its fleet.

After that, Aegina sank into geopolitical obscurity and lived the same history as the rest of Greece. The domination by Philip of Macedonia followed by Alexander the Great, then his successors, the Ptolemies of Egypt, the Roman rule (about 86 AD), followed by the Byzantine Times, the Venetian domination and the Turkish yoke until the Revolution of 1821.

Aegina played a major role in the Greek Revolution fighting against the Turks and from 1827 to 1829 the island was declared the temporary capital of the partly liberated Greece. That time the village flourished a lot and many institutions were built, such as the first secondary school in Greece and the Eunardios School by a Swiss banker. But, with the creation of the Modern Greek State in 1930, Aegina returned to its shadow and to its more humble position of the first producer of pistachio nuts in Greece.

Sounio (Temple of Poseidon):

The Ancient Greeks certainly knew how to choose a site for a temple. Nowhere is this more evident than at Cape Sounion, 70 km south of Athens, where the Temple of Poseidon stands on a cliff that plunges 65 m down to the sea. Built-in 444 BCE – at the same time as the Parthenon – it is constructed of local marble from Agrilesa, its slender columns, of which 16 remain, are Doric. It is thought that the temple was built by Iktinos, the architect of the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens’ Ancient Agora.

It looks gleaming white when viewed from the sea, which gave great comfort to sailors in ancient times: they knew they were nearly home when they saw the first glimpse of white, far off in the distance. The views from the temple are equally impressive: on a clear day, you can see Kea, Kythnos, and Serifos to the southeast, and Aegina and the Peloponnese to the west. The site also contains scant remains of a propylaeum, a fortified tower and, to the northeast, a 6th-century temple to Athena.Visit early in the morning before the tourist buses arrive, or head there for sunset to enact Byron’s lines from Don Juan:

‘Place me on Sunium’s marbled steep

Where nothing save the waves and I

May hear our mutual murmurs sweep.’

Byron was so impressed by Sounion that he carved his name on one of the columns.

Corinth Canal:

The famous Corinth Canal connects the Gulf of Corinth with the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea. It cuts through the narrow Isthmus of Corinth and separates the Peloponnesian peninsula from the Greek mainland, thus effectively making the former an island. The canal is 6.4 kilometers in length and only 21.3 meters wide at its base. Earth cliffs flanking either side of the canal reach a maximum height of 63 meters. Aside from a few modest-sized cruise ships, the Corinth Canal is unserviceable to most modern ships. The Corinth Canal, though only completed in the late 19th century, was an idea and dream that dates back over 2000 thousand years.

Before it was built, ships sailing between the Aegean and Adriatic had to circumnavigate the Peloponnese adding about 185 nautical miles to their journey. The first to decide to dig the Corinth Canal was Periander, the tyrant of Corinth (602 BCE). Such a giant project was above the technical capabilities of ancient times so Periander carried out another great project, the diolkós, a stone road, on which the ships were transferred on wheeled platforms from one sea to the other. Dimitrios Poliorkitis, king of Macedon (c. 300 BCE), was the second who tried, but his engineers insisted that if the seas where connected, the more northerly Adriatic, mistakenly thought to be higher, would flood the more southern Aegean. At the time, it was also thought that Poseidon, god of the sea, opposed joining the Aegean and the Adriatic. The same fear also stopped Julius Caesar and Emperors Hadrian and Caligula. The most serious try was that of Emperor Nero (67 CE). He had 6,000 slaves for the job. He started the work himself, digging with a golden hoe, while music was played. However, he was killed before the work could be completed.

Before it was built, ships sailing between the Aegean and Adriatic had to circumnavigate the Peloponnese adding about 185 nautical miles to their journey. The first to decide to dig the Corinth Canal was Periander, the tyrant of Corinth (602 BCE). Such a giant project was above the technical capabilities of ancient times so Periander carried out another great project, the diolkós, a stone road, on which the ships were transferred on wheeled platforms from one sea to the other. Dimitrios Poliorkitis, king of Macedon (c. 300 BCE), was the second who tried, but his engineers insisted that if the seas where connected, the more northerly Adriatic, mistakenly thought to be higher, would flood the more southern Aegean. At the time, it was also thought that Poseidon, god of the sea, opposed joining the Aegean and the Adriatic. The same fear also stopped Julius Caesar and Emperors Hadrian and Caligula. The most serious try was that of Emperor Nero (67 CE). He had 6,000 slaves for the job. He started the work himself, digging with a golden hoe, while music was played. However, he was killed before the work could be completed.

In the modern era, the first who thought seriously to carry out the project was Kapodistrias (c. 1830), first governor of Greece after the liberation from the Ottoman Turks. But the budget, estimated at 40 million French francs, was too much for the Greek state. Finally, in 1869, the Parliament authorized the Government to grant a private company (Austrian General Etiene Tyrr) the privilege to construct the Canal of Corinth. Work began on Mar 29th, 1882, but Tyrr’s capital of 30 million francs proved to be insufficient. The work was restarted in 1890, by a new Greek company (Andreas Syggros), with a capital of 5 million francs. The job was finally completed and regular use of the Canal started on Oct 28th, 1893. Due to the canal’s narrowness, navigational problems and periodic closures to repair landslips from its steep walls, it failed to attract the level of traffic anticipated by its operators. It is now used mainly for tourist traffic. The bridge above is perfect for bungee jumping.

Ancient Corinth:

Located on the isthmus which connects mainland Greece with the Peloponnese, surrounded by fertile plains and blessed with natural springs, Corinth was an important city in Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman times. Its geographical location helped it play a role as a center of, trade, naval fleet, participation in various Greek wars, and status as a major Roman colony meant the city was, for over a millennium, rarely out of the limelight in the ancient world.

CORINTH IN MYTHOLOGY

Not being a major Mycenaean center, Corinth lacks the mythological  heritage of other Greek city-states. Nevertheless, the mythical founder of the city was believed to have been King Sisyphus, famed for his punishment in Hades where he was made to forever roll a large boulder up a hill. Sisyphus was succeeded by his son Glaucus and his grandson Bellerophon, whose winged-horse Pegasus became a symbol of the city and a feature of Corinthian coins. Corinth is also the setting for several other episodes from Greek mythology such as Theseus’ hunt for the wild boar, Jason settled there with Medea after his adventures looking for the Golden Fleece, and there is the myth of Arion – the real-life and gifted kithara player and resident of Corinth – who was rescued by dolphins after being abducted by pirates.

heritage of other Greek city-states. Nevertheless, the mythical founder of the city was believed to have been King Sisyphus, famed for his punishment in Hades where he was made to forever roll a large boulder up a hill. Sisyphus was succeeded by his son Glaucus and his grandson Bellerophon, whose winged-horse Pegasus became a symbol of the city and a feature of Corinthian coins. Corinth is also the setting for several other episodes from Greek mythology such as Theseus’ hunt for the wild boar, Jason settled there with Medea after his adventures looking for the Golden Fleece, and there is the myth of Arion – the real-life and gifted kithara player and resident of Corinth – who was rescued by dolphins after being abducted by pirates.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The city was first inhabited in the Neolithic period (c. 5000 BCE) but became more densely populated from the 10th century BCE. The historical founders were the aristocratic descendants of King Bacchis, the Bacchiadae (in c. 750 BCE). The Bacchiadae ruled as a body of 200 until in c. 657 BCE when the popular tyrant Cypselus took control of the city, to be succeeded by his son Periander (re. c. 627-587 BCE). Cypselus funded the building of a treasury at Delphi and set up new colonies

From the 8th century BCE, Corinthian pottery was exported across Greece. With its innovative figure decoration, it dominated the Greek pottery market until the 6th century BCE when Attic black-figure pottery took over as the dominant style. Other significant exports were Corinthian stone and bronze wares. Corinth also became the hub of trade through the diolkos. This was a stone track with carved grooves for wheeled wagons which offered a land short-cut between the two seas and probably dates to the reign of Periander. In the Peloponnesian War, the diolkos was even used to transport triremes. Although the idea for a canal across the isthmus was first considered in the 7th century BCE and various Roman Emperors from Julius Caesar to Hadrian began surveys, it was Nero who actually began the project (67 CE). However, on the emperor’s death, the project was abandoned, not to be resumed until 1881 CE.

From the early 6th century BCE, Corinth administered the PanHellenic games at nearby Isthmia, held every two years in the spring. These games were established in honor of Poseidon and were particularly famous for their horse and chariot races.

An oligarchy, consisting of a council of 80, gained power in Corinth (585 BCE). Concerned with a local rival, Argos. From 550 BCE Corinth became an ally of Sparta during Cleomenes’ reign though, the city became wary of the growing power of Sparta and opposed Spartan intervention in Athens. Corinth also fought in the Persian Wars against the invading forces of Xerxes which threatened the autonomy of all of Greece.

Corinth suffered badly in the First Peloponnesian War, which it was responsible for after attacking Megara. Later it was also guilty of causing the Second Peloponnesian War, in 433 BCE. Once again though, the Corinthians, mainly as Sparta’s naval ally, had a disastrous war. Disillusioned with Sparta’s reluctance to completely destroy and concerned over Spartan expansion in Greece and Asia Minor, Corinth formed an alliance with Argos, Boeotia, Thebes, and Athens to fight Sparta in the Corinthian Wars (395-386 BCE). The conflict was fought at sea and on Corinthian territory and was yet another costly endeavor for the citizens of Corinth.

Corinth became the seat of the Corinthian League, but losing a war against Philip II of Macedon (338 BCE) this ‘honor’ was a Macedonian garrison being stationed on the Acrocorinth acropolis overlooking the city.

A succession of Hellenistic kings took control of the city – starting with Ptolemy I and ending with Aratus in 243 BCE when Corinth joined the Achaean League. However, the worst was yet to come, when the Roman commander Lucius Mummius sacked the city (146 BCE).

A brighter period was when Julius Caesar took charge (in 44 BCE) and organized the agricultural land into organized plots (centuriation) for distribution to Roman settlers. The city once more flourished, by the 1st century CE it became an important administrative and trade center again. In addition, following St. Paul’s visit between 51 and 52 CE, Corinth became the center of early Christianity in Greece. In a public hearing, the saint had to defend himself against accusations from the city’s Hebrews that his preaching undermined the Mosiac Law. The pro-consul Lucius Julius Gallio judged that Paul had not broken any Roman Law and so was permitted to continue his teachings. From the 3rd century CE, the city began to decline and the Germanic tribes attacked the city.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

In Greek Corinth, there were cults to Aphrodite (protector of the city), Apollo, Demeter Thesmophoros, Hera, Poseidon, and Helios and various buildings to cult heroes, the founders of the city. In addition, there were several sacred springs, the most famous being Peirene. Unfortunately, the destruction in 146 BCE erased much of this religious past. In Roman Corinth, Aphrodite, Poseidon, and Demeter did continue to be worshiped along with the Roman gods.

The site today, first excavated in 1892 CE by the Greek Archaeological Service, is dominated by the Doric peripteral Temple of Apollo (c. 550-530 BCE), originally with 6 columns on the façades and 15 on the long sides. A particular feature of the temple is the use of monolithic columns rather than the more commonly used column drums. 7 columns remain standing today.

The majority of the other surviving buildings date from the 1st century CE in the Roman era and include a large forum, a temple to Octavia, baths, the Bema where St. Paul addressed the Corinthians, the Asklepeion temple to Asclepius, and a centre of healing, fountains – including the monumental Peirine fountain complex (2nd century CE) – a propylaea, theatre, odeion, gymnasium, and stoas. There are also the remains of three basilicas.Archaeological finds at the site include many fine mosaics – notably the Dionysos mosaic – Greek and Roman sculpture – including an impressive number of busts of Roman rulers.

Acrocorinth:

The steep rock of the Acrocorinth rises to the south-west of ancient Corinth, surmounted by the fortress, also called the Acrocorinth, which was the fortified citadel of ancient and medieval Corinth and the most important fortification work in the area from antiquity until the Greek War of Independence in 1821. It is 575 m. high and its walls are a total of almost 2.000 m. in length.

The ascent to Acrocorinth – Acrocorinthos, is facilitated by a road which  climbs to a point near the lowest gate on the W side. This commanding site was fortified in ancient times and its defenses were maintained and developed during the Byzantine, Frankish, Turkish and Venetian periods. After a moat (alt. 380 m -1247 feet) constructed by the Venetians follow the first gate, built in the Frankish period (14th,c.) and the first wall 15th c. then come the second and third walls (Byzantine: on the right, in front of the third gate, a Hellenistic tower). Within the fortress we follow a path running NE to the remains of a mosque (16th c.) and then turn S until we join a path leading up to the eastern summit, on which there once stood the famous Temple of Aphrodite, worshiped here after the Eastern fashion (views of the hills of the Peloponnese and of Isthmus).

climbs to a point near the lowest gate on the W side. This commanding site was fortified in ancient times and its defenses were maintained and developed during the Byzantine, Frankish, Turkish and Venetian periods. After a moat (alt. 380 m -1247 feet) constructed by the Venetians follow the first gate, built in the Frankish period (14th,c.) and the first wall 15th c. then come the second and third walls (Byzantine: on the right, in front of the third gate, a Hellenistic tower). Within the fortress we follow a path running NE to the remains of a mosque (16th c.) and then turn S until we join a path leading up to the eastern summit, on which there once stood the famous Temple of Aphrodite, worshiped here after the Eastern fashion (views of the hills of the Peloponnese and of Isthmus).

Courses of roughly dressed polygonal masonry allow us to suppose that the Acrocorinth was fortified as early as the time of the Kypselid tyranny (late 7th c. early 6th c. BCE). The surviving parts of the ancient fortifications, however, which are at many points beneath the medieval enceinte, belong mainly to the 4th c. BCE. In 146 BCE, Mummius destroyed the fortifications of the lower city and the Acropolis. The destroyed sections were subsequently reconstructed from the s During the Middle Ages, the Acrocorinth was of prime importance for the defense of the entire Peloponnese, and held out against the attacks of the barbarians. The Byzantines sporadically repaired the walls, especially after hostile raids (by the Slavs, Normans, and others), and added new fortifications on the west side of the fortress. In 1210, after a five-year siege, the Acrocorinth was captured by Otto de la Roche and Geoffroy I Villehardouin and was incorporated in the Frankish principate of Achaea. In the middle of this century, William Villehardouin extended the fortifications of the fortress, to be followed in this by the Angevin Prince John Gravina at the beginning of the 14th c.

In 1358 the Acrocorinth passed to the Florentine banker Niccolo Acciajuoli, and in 1394 to Theodoros, I Palaiologos despot of Mystras. Apart from a brief occupation by the Knights of Rhodes from 1400-1404, the fortress remained in Byzantine hands until 1458, when it was captured by the Ottoman Turks. The Venetians made themselves masters of the Acrocorinth from 1687 to 1715, after which it reverted once more to the Turks until the Greek Uprising of 1821. The approach to the fortress is from the west side. The walls have an irregular shape, which was dictated by the form of the terrain and remained the same in general terms from the Classical period to modern times. Three successive zones of fortifications, with three imposing gateways, lead to the interior of the fortress. The fact that the same material was used for extensions or repairs to the walls frequently makes it difficult to distinguish the building phases or assign a date to them.

Nemea and Nemean Games:

SETTLEMENT

Lying in foothills of the Arcadian mountains, 333 m above sea level in a long narrow valley is Nemea. The name Nemea comes from the Greek word meaning to graze. Inhabited since Early Neolithic times (6000 to 5000 BCE) it was settled throughout the Bronze Age shown by rock-cut tombs, dating from the mid-16th century BCE to the 12th century BCE. The site reached its peak from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE then, every two years, athletes and spectators gathered for the Pan-Hellenic Games. Following the movement of the Games to Argos, the site was largely abandoned and used merely for agricultural purposes. In the 4th century, an early Christian settlement was established with a Basilica and baptistery. This settlement was itself abandoned in the mid-6th century when the valley’s river dried up.

Origins of the Games

The mythical origin of the Games is sometimes credited to Hercules. After his first labor, where he had to kill the Nemean lion, he established athletic games in honor of his father Zeus. A second and more likely mythological origin is the story of Opheltes. Lykourgos, the priest-king had a son Opheltes and seeking to protect his son, Lykourgos asked the Delphic oracle for advice. The response of the oracle was to prevent the baby from touching the ground until he had learned to walk. Opheltes was put under the care of a slave called Hypsipyle but while engaged fetching water for some passing champions on their way to Thebes (the famous Seven against Thebes) the unattended baby was fatally attacked by a snake while he slept in a bed of wild celery. Taking this as a bad omen, the champions organized funeral games to appease the gods and pay tribute to the unfortunate Opheltes.

The Events

The events of the Nemean Games were held shortly after the summer solstice. Athletes came from all over Greece and even beyond to compete and were separated into three age groups: boys (12-16 years), youths (16-20) and men (over 21). They were supervised by specially trained Hellanodikai who acted as both referees and as judges and wore black. Athletes competed naked and victors were awarded a crown of wild celery. The most important event was the stadion or foot-race over one length of the stadium track. Other events were foot-races over various stadium lengths: the diaulos (double), the hippios (four lengths), Dolichos (as many as twenty-four lengths) and the hoplitodromos (as the dialous but run in hoplite armor). In addition, there were competitions in boxing (pyx), wrestling (pale), combined boxing and wrestling (pankration) and the pentathlon – stadion race, wrestling, javelin (akonti), discus (diskos) and long jump (halma). Horse races were also held on the hippodrome track and included the four-horse chariot race of 8,400 m (tethrippon), the two-horse chariot race of 5,600 m (synoris) and the horse race of 4,200 m (keles). Two further competitions were for heralds (kerykes) and trumpeters (salpinktai). The winner of the first won the right to announce the sporting events and victors and the latter won the privilege of announcing the herald. In the Hellenistic period competitions in singing, flute and lyre playing were also added.

ARCHITECTURAL REMAINS

In 1884 a French archaeologist made surface excavations. Excavations were also carried out between 1924-6 by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and again in 1964. Then more systematically from 1973 by the University of California at Berkeley, which continues to the present day.

Remains at the site are dominated by the impressive Temple of Zeus constructed (330 BCE). This was built on the site of an earlier temple (6th century BCE). The new temple was built of local limestone and covered in fine marble-dust stucco with the inner sima in marble. The entrance had a large ramp rather than steps and inside was a large statue of Zeus. The temple measured approximately 22 x 42 m. The Doric exterior (peristyle) had 6 x 12 unusually slender columns, 10.33 m high. The Corinthian inner columns (6 x 4) also supported a secondary story of Ionic columns. There was no exterior decoration. The wooden and terracotta tiled roof of the temple collapsed in the 2nd century CE and in the 5th century CE, the majority of columns collapsed, due to the removal of blocks from the stylobate. Several columns have been re-erected in modern times mostly using the original drums which still lie scattered around the site.

Alongside the Temple of Zeus was an unusually long (41 m) altar but only its foundations survive. Also near the temple, there is a row of nine small rectangular buildings (oikoi) built in the early 5th century BCE. In the 4th century BCE, the Macedonians added other buildings. These include a Bathhouse, the large Xenon building, a shrine to Opheltes and a triple stone reservoir. The Bathhouse has a large central pool flanked by two tub rooms, each with four stone wash basins. The Xenon was a large rectangular building (85 x 20 m) with fourteen rooms and originally two stories but only the foundations remain (probably used as accommodation for athletes and trainers). The shrine to Opheltes was built on a small man-made mound and covered an area of 850 square meters enclosed by a low stone wall. Inside were two altars, a cenotaph to commemorate Opheltes and at least some trees, planted to form a sacred grove in a corner. The shrine was a renovation of the earlier 6th-century one. The triple reservoirs measure 3 x 9.8 m and reach a depth of 8 m; their exact function is not known.

Linked by a road to the sacred complex, the stadium of Nemea which is visible today dates from 330-320 BCE and was built between two natural ridges providing an elevated vantage point for spectators and allowing a capacity as high as 30,000 people. A locker-room (apodyterion), once with an open central court, is connected to the stadium track by an arched tunnel measuring over 36 m in length and nearly 2.5 m in height. The track itself is the usual 600 ancient feet in length (178 m) with small marker posts indicating every 100 ft. Still in situ is the stone starting line (balbis) where athletes placed their front foot.

Important archaeological finds at the site include a rare double-tray sacrificial table and a range of bronze sporting equipment including javelin tips, strigils, and a discus. Other finds include votive statues, jumping stones and an impressive array of coins and pottery which attest to the wide geographical appeal of the Nemean Games. Since 1996 and held every four years, there has been a revival of the ancient Nemean Games with footraces held in the ancient stadium.

Nafplio:

The city of Nafplio was the first capital of the modern Greek state. Named after Nafplios, son of Poseidon, and home of Palamidis, their local hero of the Trojan war and supposedly the inventor of weights and measures, lighthouses, the first Greek alphabet and the father of the Sophists. The small city-state made the mistake of allying with Sparta in the second Messenia War (685-688BC) and was destroyed by Damokratis the king of Argos.

Because of the strength of the fort that sits above the bay, the town of Nafplio became an important strategic and commercial center to the Byzantines from around the sixth century AD. In 1203 Leon Sgouros, ruler of the city, conquered Argos and Corinth, and Larissa to the north, though it failed to successfully conquer Athens after a siege in 1204.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, the Franks, with the help of the Venetians captured the city and nearly destroyed the fortress in the process. In the treaty, the defenders of the city were given the eastern side of the city, called the Romeiko and allowed to follow their customs, while the Franks controlled the Akronafplia, which was most of the city at the time. The Franks controlled the city for 200 years and then sold it to the Venetians. The Venetians continued the fortification of the upper town and completed their work in 1470. That same year they built a fort on the small island in the center of the harbor called the Bourtzi. To close the harbor the fort was linked by chains and the town was known as Porto Cadenza, meaning Port of Chains. During this period people flocked to the safety of the fortified city in fear of the Turks and forced the expansion of the city into the lagoon between the sea and the walls of the Akronafplia. The new additions to the city were surrounded by walls and many major buildings were erected including the Church of Saint George. But these new walls didn’t matter because in the treaty with Suleiman the First, Nafplio was handed over to the Turks who controlled the city for 100 years and made it the primary import/export center for mainland Greece.

the city for 200 years and then sold it to the Venetians. The Venetians continued the fortification of the upper town and completed their work in 1470. That same year they built a fort on the small island in the center of the harbor called the Bourtzi. To close the harbor the fort was linked by chains and the town was known as Porto Cadenza, meaning Port of Chains. During this period people flocked to the safety of the fortified city in fear of the Turks and forced the expansion of the city into the lagoon between the sea and the walls of the Akronafplia. The new additions to the city were surrounded by walls and many major buildings were erected including the Church of Saint George. But these new walls didn’t matter because in the treaty with Suleiman the First, Nafplio was handed over to the Turks who controlled the city for 100 years and made it the primary import/export center for mainland Greece.

In 1686 the Turks surrendered the city to a combined force of Venetians, Germans and Poles, lead by Vice Admiral Morozini and this began the second period of Venetian rule in which massive repairs were made to the fortress and the city including the construction of the fortress in Palamidi. When the Peloponnese falls to the Venetians, Nafplio becomes the capital. But after just thirty years the Turks once again take control of the city, almost totally destroying it, looting it and killing almost all its defenders. Most of the survivors chose to leave and the city while the Turks built mosques, baths and the homes in the eastern style which can still be seen.

In April of 1821 Greek chieftains and Philhellenes surrounded the city of Nafplio and liberated it from the Turks under the leadership of Theodore Kolokotronis. Nafplio became the center of activities which would result in the formation of Modern Greece. In 1823 it becomes the capital of the state which is then recognized by the world powers (England, France, and Russia) in 1827.

In January of 1828, Ioannis Kapodistrias is recognized as the first governor and arrives in Nafplion. In 1831 King Otto is chosen as the first King of Greece but a month later Kapodistrias is murdered in the Church of Agios Spiridon.

In January of 1828, Ioannis Kapodistrias is recognized as the first governor and arrives in Nafplion. In 1831 King Otto is chosen as the first King of Greece but a month later Kapodistrias is murdered in the Church of Agios Spiridon.

In 1833 King Otto arrives amid great fanfare to the city of Nafplio where he remains until 1834 when the capital of Greece is moved to Athens.

In 1862 there is a rebellion in Nafplio against the monarchy. A siege by the royal army follows. The rebels are given amnesty in 1862. In 1834 Kolokotronis is jailed in the Palamidi fortress. After the capital moves to Athens, the city of Nafplio becomes of less importance. But it still continues to attract visitors to this very day because its history is virtually the history of modern Greece and because every occupying power has left its mark.

The city of Nafplio is like a living museum. It’s also as lively as any city in Greece.

Cancellation Policy

- All cancellations must be confirmed by Olive Sea Travel.

- Regarding the Multiple Day Tours: Cancellations up to 7 Days before your service date are 100% refundable.

Cancellation Policy:

-

- Licensed Tour Guides and Hotels are external co-operators & they have their own cancellation policy.

- Apart from the above cancellation limits, NO refunds will be made. If though, you fail to make your appointment for reasons that are out of your hands, that would be, in connection with the operation of your airline or cruise ship or strikes, extreme weather conditions or mechanical failure, you will be refunded 100% of the paid amount.

- If your cancellation date is over TWO (2) months away from your reservation date, It has been known for third-party providers such as credit card companies, PayPal, etc. to charge a levy fee usually somewhere between 2-4%.

- Olive Sea Travel reserves the right to cancel your booking at any time, when reasons beyond our control arise, such as strikes, prevailing weather conditions, mechanical failures, etc. occur. In this unfortunate case, you shall be immediately notified via the email address you used when making your reservation and your payment WILL be refunded 100%.